The Lotus Elite/Eclat/Excel range still labours under a reputation for unreliability. But this isn’t really deserved and hides the fact that these cars have a huge amount to appeal to the enthusiast today.

Despite their reputation for poor reliability and flaky build quality, the Lotus Elite/Eclat/Excel might well be the ideal classic sports cars. Why? Well, glassfibre bodies that could never rust, race-honed engines, chassis tuned by focused brains that prized tactility above all else. And despite featuring much more in the way of comfort and luxuries than an Elan, they still only just creep over the one-ton kerb weight mark. Okay, they could be troublesome, but that’s no reason to stop you pulling the trigger on what may be one of the most entertaining cars you’ll ever own.

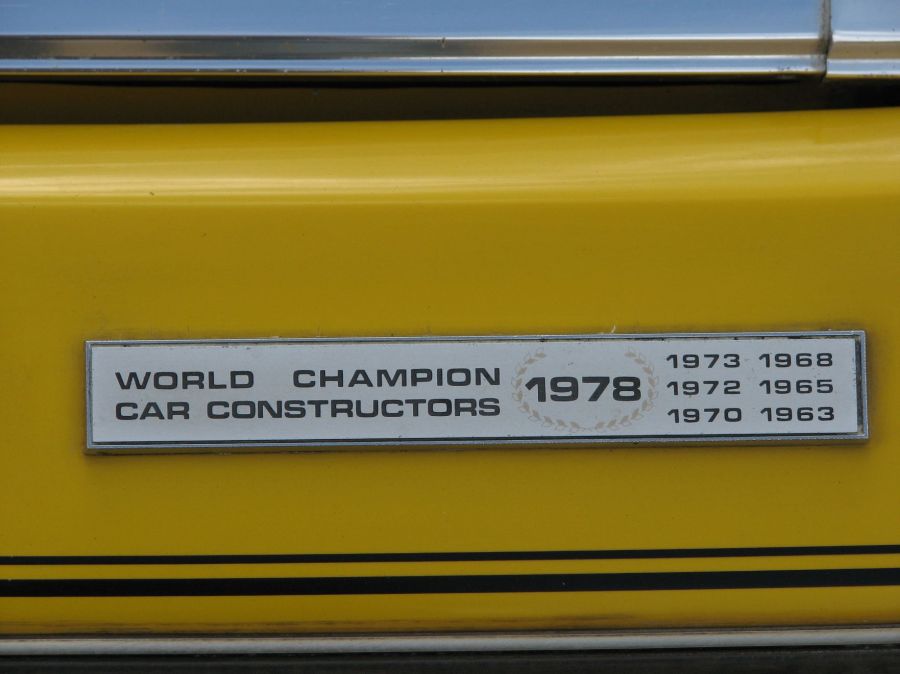

We’re looking at three individually named models here, but they’re all fundamentally similar. The Elite (and we’re talking about the one launched in 1974, of course, rather than the 1950s coupé) was the model that replaced the Elan +2, offering proper four-seat accommodation – well, sort of – and the practicality of a shooting brake, meaning that the discerning parent could imbue a sense of adventure into their sepia-tinted family holidays, possibly scaring the wits out of the kids around a race track along the way. It was the first Lotus to use the aluminium block DOHC 16-valve 907 engine, with 155bhp (very impressive for a 2.0-litre engine in the mid-1970s) and offered four-wheel independent suspension and oh-so-period spaceship looks.

The Eclat was based on the Elite, but featured a rakish fastback body and was the successor in spirit, if not in style to the much-loved Elan. Later cars came with the 2.2-litre 912 engine – similar power, but with more torque – as well as a Getrag gearbox rather than the early unit with Austin Maxi origins. And the Excel? This pushed the platform right through to the early 1990s with its contemporary styling upgrades, and it benefitted from Lotus’ new deal with Toyota, adorning the Excel with the gearbox, differential, driveshafts, wheels and doorhandles from the Supra.

It pays to exercise caution when buying a classic Lotus, of course, but the relative undesirability of these models will work in your favour: Most collectors will want an Elan, but there are enough people out there restoring and looking after Elites and their brethren to ensure a decent showing of quality cars on the market.

Bodywork and chassis

The thing that will destroy a 1970s Lotus, your finances and quite possibly your love of old cars is structural corrosion. Like nearly all Hethel-built cars, the Lotus Elite/Eclat/Excel trio feature a ‘spine’ chassis and body frame made of tubular steel with moulded GRP body elements. The plastic body is corrosion resistant, but the steel parts are most certainly not. Series 2 cars (from 1980 onwards) had galvanised chassis frames which greatly ease the worries here – but contrary to belief even the galvanised frames can rust. Earlier cars suffered horrific structural rust, with some needing replacement frames after just three or four years. S1 examples that have been rebuilt or restored will likely have galvanised frames and given this it is best to steer clear of one still on a mild steel frame unless it is immaculate. Also beware chassis that have had new tubes or repair sections welded in to replace rotten parts – poor-quality or homemade parts won’t have the same rigidity as the Lotus-spec metal, and that will also depend on the quality of the welding. In the long run it would be easier, cheaper and would result in a better-driving car to fit a new chassis rather than patch up a bad original one – but that’s still a big job that would cost more than the car would gain in value.

The worst area is the crossmember between the rear suspension turrets since this is not only prone to collecting water and dirt from the road but is hard to see and structurally vital. If allowed to corrode away unchecked, it will eventually reach a point where the suspension mounts will collapse. The best way to check this is from underneath with the car on a lift. Other crossmembers and outriggers are vulnerable, especially around the body mounts which include felt pads that retain water. On S1 cars the hollow front cross-tube serves as the vacuum reservoir for the system that operates the pop-up lamps, and if the chassis corrosion gets to the stage where this is holed, it won’t hold vacuum. The lights are held down by vacuum and pop up in its absence, so if looking at a car where the lamps won’t go down (or you’re looking at an advert where the car is only pictured with the headlamps up) then be suspicious and make a careful check of the cross-tube. The vacuum system is especially finnicky with age, though, so it could be a less serious issue.

The bodywork itself is, fortunately, rarely an area of concern. The Elite/Eclat twins introduced new body moulding and painting techniques. The bodies were created in two halves (trim line running along the flanks – chrome on S1 cars and black plastic on the Lotus Excel -hides the join) formed by vacuum, allowing lighter, smoother and more consistent shapes while Lotus was able to achieve a good high-gloss paint finish in keeping with the cars’ more upmarket price and market position. This means that patches of poor paint and cracked or crazed gelcoat indicate repaired accident or parking damage, and wobbly surfaces show where filler or repair sections have been badly fitted. Cars that have spent most of their lives outside will tend to show faded paint and more crazing in the gelcoat, but so long as the plastic itself is in good condition this is purely a cosmetic issue. Putting it right will require a specialist with specific skills in doing good work with GRP bodywork though, so don’t pay over the odds for a car with a rough-looking body.

Engine and transmission

The 900-Series engines used across the Lotus Elite/Eclat/Excel series are not as highly strung as their reputation may suggest, but they do need regular care and maintenance. Check the condition and the quantity of the oil in the sump, since the engines are known for burning oil at a fair rate even when in top-notch condition (up to two litres every 1000 miles is considered normal, and the sump only holds six litres of oil). Oil leaks from the cam covers is also a common fault, although a modern improved gasket can banish that. Look for oil seepage at the top end and see if it’s pooling in the spark plug wells. If it does, it can cause hard starting or misfires which vanish when the oil is cleaned up. The engines are generally otherwise oil tight, so leaks from the crank seals or filler cap indicate worn bores. Best walk away at this point because rebuilding a 900-Series engine to the correct standard is a very expensive job.

All cars in this trio had twin Dell’Orto carburettors which hold their tune well, but do suffer worn jets and spindles with age. This will put them out of balance, symptoms of which include rough or even idling and surging when running at constant engine speeds on light throttle. Also be suspicious if the idle speed is too high, since it may have been adjusted upwards to hide an engine that won’t idle smoothly. Rebuilds are not expensive or difficult, though.

The cambelt should be changed every 24,000 miles or two years (note that last point on cars that see little use) so you want to see proof of that in the car’s history. The same interval ideally applies to coolant changes, which the all-alloy engines need to prevent corrosion or sludging of the internal passages. This is what is usually behind any overheating (the engines generally keep their cool unless something is wrong) but it might be a corroded radiator. Exhaust pipe sections are available but expensive due to the complex curvature so check the pipework carefully for holes or rust spots.

Four manual gearboxes are used across the Lotus Elite/Eclat/Excel series. Base-spec Eclats used a four-speed Ford Cortina gearbox. Other S1s used a bespoke transmission casing with five-speed Austin Maxi internals. The S2s used a Getrag unit and the Excel had a Toyota one shared with the Supra. The Eclat and Elite were also available in their range-topping forms with a three-speed Borg Warner automatic, which was replaced by a ZF 4-speed in the Excel. The only unit to really worry about is the S1 five-speed unit – it was originally developed for the Elan +2 and the Maxi bits are really not up to the job of dealing with the torque of the bigger engine and the loads imposed by the heavier Eclat and Elite. Parts are also scarce so rebuilds will be difficult and expensive. Be sure that the synchromesh isn’t worn (crunching downchanges) and that there are no shrieking bearings or knocking teeth. The Ford four-speeder is a bit crude but strong and parts are readily available to rebuild a tired ‘box. The Getrag and Toyota units are strong and essentially trouble free. The automatics are also not given to particular trouble, the ZF unit especially, and both can be rebuilt if they are worn. But it really wouldn’t be worth it unless the rest of the car was especially good. Check for smooth drive engagement, quick gear changes and a functional kick-down function.

Watch for wear in the driveshaft universal joints, especially in the Eclat/Elite, which are prone to wear. They were also prone to vibration and ‘booming’ even when new, especially on S1 cars. But any loud graunching noises, knocks from worn joints, a sense of binding under power or similar signs point to trouble, but replacement parts are available off the shelf and not difficult to fit. The Excel has more durable and sealed-for-life Supra driveshafts.

Suspension, steering and brakes

The manufacturer picked and chose from the BMC, Triumph and Ford bins for the Lotus Elite/Eclat/Excel, which pays benefits all these years later since parts are nearly all easy to source and the foibles of all them are well understood.

Front suspension uprights and trunnions are from the Triumph Herald, and so need regular lubrication with gear oil – not grease. Ask the owner what they’ve used, and check for grease (or its absence) around the uprights and lubrication points. Rock the front wheels when they’re off the ground to check for play in the bearings, hubs, uprights and steering joints. Bad wear in any of these areas will also show up as wandery, woolly steering on a test drive, but so long as lubrication has been up to scratch the low weight of the Lotus means that they don’t wear quickly. The rear suspension is more bespoke with the typical Chapman struts and lightweight A-frame wishbones – it doesn’t suffer from any particular issues beyond rust in the mounting points. Do give the rear wheels on Eclat/Elite models the ‘wobble’ test as well, since the Austin Maxi rear wheel bearings need re-greasing occasionally and this is often neglecting, leading to wear and noise. Various bushes (such as the anti-roll bar mounts) are from the Ford Escort, so replacing any worn parts is not an issue.

The steering joints are from the Escort as well (except on the Excel where the compatible model is, of all things, the Leyland-DAF 200 Series – formerly the Leyland Sherpa!) and the steering rack is Ford Capri for cars with power steering and Ford Escort for those without.

The brakes are discs at the front and, on the Elite/Eclat, inboard drum brakes at the back. The low-spec Eclats (the ones that also have the Ford gearbox) have Triumph Vitesse front brakes, while others use unique discs with Jaguar XJ6 callipers. The rear drums were originally MGC or Ford Capri depending on the age of the car, and the system is run by a Ford Escort Mk2 master cylinder and servo. The Excel switched to outboard rear brakes with discs, using Toyota Supra parts. Handbrake rigging is either from the Ford Escort (on the Eclat/Elite) or the Toyota Celica (on the Excel). The only real thing to watch is for problems with the inboard rear brakes on the earlier cars – access if very awkward which means that they are often neglected, and putting right any issues is difficult. Look for signs of leaking wheel cylinders, listen for shoes worn down to the metal and feel for vibrations through the pedal caused by warped drums. Sponginess in the pedal could also point to trouble with worn or leaky cylinders and it’s nearly always the ones at the back.

All of this suffices to say that virtually all the running gear on these cars is readily available and you can often save a pretty penny if you can track down the parts ‘at source’ rather than buying Lotus-branded parts. None of these parts are especially fragile or troublesome, and you will mostly be faced with problems of general wear, age or neglect. Don’t be too gung-ho though, since the cost of these parts can quickly add up to the point where you may as well have bought a better car in the first place.

Interior, trim and electrics

The Elite/Eclat was a big step for Lotus in terms of finish, comfort, refinement and equipment. These were supposed to be luxurious sports tourers with cockpits to rival what the Italians and Germans were producing. Ambition slightly outstripped Hethel’s abilities in this time period, with poor-quality materials and fit from the start, and much of the interiors was made of materials that didn’t wear or age well. So there’s a lot of stuff to look at, a good chance that it will be shabby, and most of it is not easy to find if it is broken. If you’re planning on using a car only for occasional use or weekend fun, a more basic Eclat or Elite makes sense as having less stuff to go wrong. The Excel also benefited from noticeably better materials and build quality, as well as using more readily available instruments. Depending on the era switchgear came either from the British Leyland or Toyota parts bin, but it can be surprisingly expensive to source new so broken or non-functional switches should be checked and avoided.

A typical Elite or Eclat’s cabin will be a riot of 1970s synthetic materials in a controversial colour. If it’s shabby, torn or stained, or just too much of a fashion crime by your tastes, it can all be ripped out and replaced with the services of a trim specialist, but it will cost. An interior in bad condition (they are prone to sagging headlinings and worn seats) can be a good haggling point.

Corrosion, perished seals and cracked plastics can cause water leaks which cause havoc on the interior of all three cars. Damp carpets and footwells (or even mouldy rear seats) are usually caused by rusted steel seat mounting brackets which expose the mounting holes and suck up water when the car moved forward in wet weather or through puddles. The sealant around the rear windows on Eclats and Excels also hardens and cracks with age, leading to rainwater getting in. Hardened or shrunken door seals, perished speedo cable sealing grommets, failed wiper spindle seals and poor windscreen seals (usually happening on cars that have been stripped and restored) can all cause water to get into the front footwells and behind the dashboard, where it wreaks havoc on the fusebox and electrical relays.

Speaking of, electrical parts are also often from other common classics (S2s use Triumph TR7 headlamp mechanisms for instance) but they’re often not easy to find – you can’t walk into a motor factor and buy Hillman Hunter or Rover SD1 lamp units any more. Check that the heater and fan blows properly (it’s a common failure). Many of these cars came with air conditioning – whether it’s working or not is a priority is up to you, but if the car is top money it really should. If a car has a perpetually misty windscreen and a damp smell then check the heater plenum drains are clear.

Lotus Elite, Eclat & Excel: our verdict

For three models that are fundamentally the same, the Lotus Elite/Eclat/Excel cover a lot of ground, from the commercially unpopular and oh-so-1970s Elite to the rugged and handsome late-model Excel. They’re all filled with Lotus pedigree and are joyous to drive, and none really deserve the ‘Lots of Trouble Usually Serious’ reputation these days, so long as you avoid thoroughly tired and neglected examples. In terms of desirability, these cars follow the familiar inverse bell curve, with the very early and very late ones being the most prized. Collectors and Lotus diehards will prize the purity and rarity of an early Elite or a basic four-speed Eclat, while for practicality, performance and reliability a late Excel is hard to beat for a car that offers Lotus dynamics with surprising practicality. What models gain in practicality they lose in collectability so, for instance, despite their many improvements, there is not a noticeable premium on S2 cars over S1s.

While not as spurned as they once were, prices for all three models are surprisingly low at the moment – for what would buy you a good but not exceptional MGB GT or Reliant Scimitar you could be driving a really nice Lotus Elite – in fact £5000-7500 would get you a solid, driving but unexceptional example of all three. But at that level they would probably have faded or bleached bodywork and tatty interiors. Go up to £7500-10,000 and you’re getting into the realm of cars without any stand-out faults, all mechanical parts in good condition and presentable interiors. In five-figure territory comes the very best examples, with Eclats and Excels topping out at £15,000 or so and Elites going up to £17,500.

Lotus Elite, Eclat & Excel timeline

1974

Lotus Type 75 Elite introduced, with 2.0-litre 155bhp Type 907 engine and a 2+2 shooting brake body. Available in three trim levels – 501 (base), 502 (with air conditioning) and 503 (with air conditioning and power steering).

1975

Lotus Type 76 Eclat launched, with the same chassis and drivetrain as the Elite but in a more conventional fastback coupe body. Basic Elite 520 had four-speed transmission, steel wheels and smaller front brakes. 521, 522 and 523 models were specced as per equivalent Elite. The 520 and 521 were also available in Sprint form with unique black/white paint scheme and various engine and running gear upgrades.

1976

Three-speed Borg Warner automatic transmission introduced as an option, available on new range-topping 504 (Elite) and 524 (Eclat) models.

1980

Series 2 Elite (Type 83) and Eclat (Type 84) introduced with 2.2-litre Type 912 engine of the same power but usefully more torque. Getrag five-speed manual gearbox now fitted as standard, plus a galvanised chassis frame and electrically worked headlamps.

1981

At the end of the year the Elite is withdrawn from production after 2535 examples are made.

1982

The Type 89 Eclat Excel is launched – a heavy re-engineering of the Eclat requiring a different chassis and incorporating a restyled, more rounded body of the same basic shape. Type 912 engine is retained, but now with numerous Toyota-sourced drivetrain and running gear parts such as 5-speed gearbox, differential, driveshafts and four-wheel disc brakes. This replaces the original Eclat, of which around 1500 had been built. Same options/model structure as the Eclat.

1983

New body-coloured bumpers, a louvred bonnet, rear spoiler and optional (Toyota Supra) alloy wheels more clearly differentiate the Eclat Excel from the previous Eclat.

1984

The new model simply becomes the Lotus Excel. Front arches are reprofiled with more flare and the boot aperture is enlarged.

1985

The Excel SE is launched in October with a higher-compression engine with tri-jet carbs and 180bhp, identified by red cam covers. All Excels gain redesigned and more upmarket fascia with improved heater. Toyota-sourced windscreen wipers and headlamp motors fitted.

1986

Excel SA with four-speed automatic transmission added to the range, also coming with cruise control, central locking and a wood-panelled dashboard.

1988

The Excel is facelifted with reprofiled bumpers, spoilers, bonnet panel and new door mirrors (from the Citroën CX) plus revised suspension giving better ride and body control.

1992

Lotus Excel production ends with 2075 built.