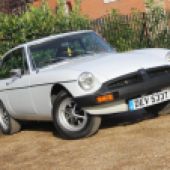

The MGB GT has remained a popular and well-supported classic for decades. But there are still plenty of pitfalls to bear in mind when buying

Words: Jack Grover

The MGB GT was announced at the 1965 London Motor Show. Mechanically it was near-identical to the roadster (which had already marked itself as the best-selling MG model of all time). The 95bhp 1.8-litre B-Series engine was the same, as was the four-speed gearbox. The steering and suspension was the same, bar that the GT came as standard with a front anti-roll bar and it had uprated rear springs to allow for the extra weight. The rear axle was an integral Salisbury-type rather than the roadster’s banjo-type unit inherited from the MGA (which proved rather noisy when mated to the ’B’s monocoque structure and this was not acceptable for the closed GT).

The GT weighed 115kg more than the roadster, which blunted its acceleration, but the streamlined shape did allow the GT to reach a slightly higher top speed than the convertible (104mph against 102mph) and return slightly better average fuel consumption. The balanced weight distribution that was key to any MG’s handling prowess was also retained – while the roadster was very slightly nose heavy, the GT carried a very slim majority of its one-up weight at the rear. The only other difference was that the GT came as standard with a heater, which the roadster would not gain as standard equipment until 1969.

The MGB GT was the perfect package – it was innately handsome with perfect proportions and fine lines. It had sufficient and fully accessible performance to be worthy of the MG badge and still be a sports car. It had fine steering, handling and road holding. It had accurate, weighty steering and a wonderfully slick short throw gearchange. It had a tough, simple, gutsy and reliable engine that could take a lot of tuning work. And yet it also had a cabin worthy of a mid-size saloon with comfortable accommodation for two six-foot adults. The rear bench provided sufficient space for two children or one tolerant adult passenger, but could also fold flat to provide a large, low boot floor accessed through that big lifting tailgate.

The addition of a tin-top roof kept the British weather at bay and allowed long periods of high-speed, long-distance cruising when the buffeting and whistling of a ‘B with the hood up or down would be wearing. It was a unique proposition in 1965 and, despite challenges from the Ford Capri, the Reliant Scimitar and the Volvo P1800ES, remained unmatched for its breadth of capabilities right to the end of production in 1980.

As early as 1967 sales of the GT in Britain exceeded those of the roadster, and by a considerable margin – by 1970 the ratio was ten GTs to every convertible. The export market still preferred the roadster, which always made up the majority of sales in those markets and overall GTs represented about a third of MGB production. There were just short of 65,000 MGB GTs sold on the British home market against just over 60,000 sold elsewhere in the world.

In short, the GT is really Britain’s favourite version of the MGB and the one that we took to heart, and this remained the case even when the ’B suffered the indignities of the rubber bumpers raised ride height in the 1970s as a sop to American safety legislation. Contrary to popular belief, MGB sales remained remarkably buoyant throughout the rubber bumper era, and the GT would have its second best sales year in 1978.

The GT remains popular today for all the reasons it has been popular since 1965 – a quick search of the online free ads will show dozens for sale at any one time and a similar number will probably be found at any decent-sized car show you care to name. But don’t let that familiarity breed contempt. Not all MGB GTs are equal and they can be very expensive to put right if you end up with a bad example – which is doubly frustrating when there are plenty of good ones out there.

Bodywork

As an all-steel monocoque car designed in the 1950s and built in Britain, it is unsurprising that structural corrosion is your biggest concern. The MGB GT is one of those cars that can hide serious rot quite well until it becomes unavoidable…and almost unfixable. All the parts are available, from repair patches to individual panels to complete body shells so anything can be fixed. But it will be costly, and it’s easy to quickly exceed the value of the car when putting right deep-seated rust in multiple areas. Bear in mind that a new GT bodyshell is priced at over £15,000 just for the bare shell and then compare that to our guide prices below.

It’s also unfortunately common to find MGBs that are something of a patchwork of quick fixes, ‘temporary’ repairs and previous owners keeping rust at bay where it appears in the more superficial areas while not eliminating it at source. These cars will not only prove to be a headache (and a financial burden) in the long term but will not drive as well as an MGB should and could even be dangerous if shiny and solid outer panels are hiding rotted-out structural innards.

The main trouble spots that must be inspected closely are: the sills, wheel arches, wings, door bottoms, scuttle, the bonnet and the tailgate.

The MGB’s sills provide much of the strength of the body, even on the GT, and are hefty and complex structures. They have inner and outer sections, with a vertical membrane panel in the middle of the closed box section they form when together, while the bottom of the inner section is closed by a separate ‘castle panel’ (so called because of its crenellated shape) which also helps attach the inner sill panel to the floor. At the jacking points a triangular reinforcer is fitted inside the inner sill to spread the load.

This creates a lot of voids and traps, which are in theory kept dry by a number of drain holes: on the outside of the sill there are four drain holes to clear water from the outer sill cavity, while on the underside are two holes to drain the inner sill and castle section near the front of the sill and another towards the rear. These are easily blocked by accumulated mud (especially the front castle section drain holes) and can also be rendered useless when new sill panels are simply welded straight over old originals. Check that the drain holes are present, clear and in solid metal and that the body seams under the doors (the front a continuation of the door shut/wing joint, the rear one running just forward of the rear curve of the door bottom) are visible and not welded up or filled over. Be especially attentive around the jacking points.

The floor panels and footwells need to be checked. Rust along where the floor joins the inner sill can spread to or from the sills depending on where moisture has got in. Lift the carpets and gently tap along the sill to feel for solid metal – the bright metal sill finishers worn by many MGBs are a hinderance here. As built the floor panel was flat and was seam welded between flanges on the inner sill (top) and the castle rail (bottom), but replacement floor panels often include an extra flange to replace the lower part of the inner sill as well – this can be a good ‘tell’ as to what work has been done on a car previously.

Rust in the footwells is more likely to be due to water getting in from a rusted-out heater plenum, leaky windscreen seals (either because the seal has perished and/or because of rust in the screen frame) or a rotten scuttle panel. Damp carpets, musty smells and foggy windows are all warning signs here – by the time rust is visible either on the outside around the scuttle vent or inside around the heater box looking up from the footwells the corrosion will be well advanced. Check the area around the door hinges and be especially cautious if the doors show any sign of dragging or catching on the sills, since this can mean that the bulkhead itself is sagging due to internal rust (it may just be worn hinges but be very sure where exactly the unwanted movement is coming from). Effectively repairing this sort of rot requires a full strip down and potentially a new shell.

The inner wings are also structural. The footwells extend into the inner wing structure, with a box section for the occupants’ feet effectively forming the back of the wheel well. This is braced to the inner wing panel by a triangular ‘trumpet section’, which is also a box cavity. Both the footwell box and the trumpet section have flat, exposed upper surfaces with no drains, so road muck and water accumulate here, sits and rots out the metal. Have a good feel by hand and by gentle taps with a screwdriver or hammer to check it’s all really solid.

The outer front wings go at the bottom rear corners where they abut the sill and the footwell (often spreading rot to both if the area has become packed with debris), the wheel arch and around the headlamp bowls. Repair panels for these areas are not too expensive to put in so long as the rest of the panel, and the inner wing it attaches to, is solid. Glass fibre wing panels are available and are not a bad thing to see so long as the paint finish is up to standard and they’re not hanging off rusty steel.

The door skins go at the bottoms at first, and then at the tops where water gets in from the window gutters. New skins are readily available. The frames usually last longer, but if the windows don’t wind smoothly then they’ve probably rusted out and this is much more expensive to sort out. A lot of MGB GTs have had a sunroof (Webasto or similar style) fitted. This is generally a good thing as it combines the advantages of a roadster and the GT but check around the frame for corrosion and be sure that the roof itself is in good condition, doesn’t have any holes or thin patches and it folds and slides correctly since they can be expensive to overhaul or repair.

The rear wings are welded in, not bolted on, which makes replacement more involved and expensive. The same warnings about the wheel arch and the area around the lamps applies as at the front. The top seam harbours rust, so check this carefully. While in this area, smell for escaping petrol fumes from a rusted-out filler neck; in bad cases the rust can perforate the join between the filler pipe and the fuel tank. In this general area also be sure to check under the rear seat for corrosion in and around the battery tray(s).

Underneath at the back, check the solidity of the floor around the rear spring mounts and hangers and the boot floor, especially around the spare wheel well. The GT’s party piece tailgate is a double-skinned steel affair which can rust at the rear lip if water accumulates inside. This is usually from a perished screen seal, which can also cause bubbling paint around the seal itself. At the other end of the car, the bonnet needs checking for rust around the hinges and corners. Before 1970 the bonnet panel was aluminium alloy, which lasts better but is more prone to being dented and can pick up areas of electrolytic corrosion if the paint is broken, and this is expensive to repair.

Engine and gearbox

You can breath much easier once onto the realm of mechanical checks, since the MGB GT is very much in the MG tradition of sturdy and simple running gear, and few other classics are blessed with such comprehensive parts support. Even the most drastic repair and refurbishment to the car’s mechanical parts won’t be anything like as costly as work to a similar scale on the body.

All MGB GT’s have the five-bearing version of the 1.8-litre B-Series engine, so robustness is not in question. Oil pressure with a warmed-up engine should be at least 40psi at 40mph in top gear, and a really healthy engine should show around 60psi. Regardless of the gauge, listen for rumbling from the bottom end under load. Clouds of blue smoke on start-up and the over-run usually mean the valve guides and stem seals are worn, while smoke on acceleration points to worn cylinder bores. Some quiet tapping from the valve gear at idle is normal, but if it’s more of a chatter or rattle then the valve guides and/or timing chain are probably worn.

Gauge the overall health of the engine by seeing if there is any blow-by being expelled from the oil filler cap with the engine idling (there should be little to none). Check for clean coolant with a good mix of anti-freeze. An MGB should have no trouble keeping its cool in British conditions – on later cars check the electric fan kicks in when it should. Throttle response should be sharp and the engine should pull cleanly at all speed/load combinations. Reluctance, flat spots or bogging down usually mean the carburettors are worn or out of balance, but a full rebuild by a specialist will only be a couple of hundred pounds. Missfiring or difficult starting is more likely to be ignition related – electric ignition is a useful addition to see.

Although the GT could be had with a three-speed automatic transmission very few were sold, so the vast majority will have a four-speed manual gearbox. Broadly the same unit was used throughout production, but very early GTs (before 1967) lacked synchromesh on first gear. An overdrive unit was a optional extra from the start of GT production and became standard from 1977.

None of these units suffer from any particular issues – just check that the gearbox runs quietly (gear whine is minimal in all speeds), shifts up and down smoothly, doesn’t jump out of gear if the throttle is suddenly released and doesn’t rattle in neutral. The clutch is on the heavy side but should be smooth and progressive – ‘swishing’ sounds when the pedal is down indicate a worn thrust bearing. The overdrive unit is cycled electrically. If it doesn’t engage at all the problem is likely with the electrical circuit or the activation solenoid, while if it struggles to stay engaged under load the issue is more likely to be the clutch or the unit being generally worn. It may be that the wrong gear oil is used – multi-grade engine oil should be used in gearboxes with an overdrive, with EP90 in those without.

The rear axle is as durable as the rest, although with age and miles the final drive unit can start droning. This is not indicative of any immediate or serious problem but could be a haggling point on an otherwise decent car, and equally a car with a silent differential is probably in tip-top condition. Check for signs of leaks around the drive pinion and the differential rear casing plate – the gasket here often perishes and drops oil. Listen for rumbling or other sounds of protest from seized or worn universal joints in the driveshaft, and ideally get under the car (with it properly supported) and twist the shaft back and forth to look for slop in both the joints and the splines.

Suspension, steering & brakes

Your first priority with the suspension should be the front kingpins. These need greasing every 3000 miles or so to prevent rapid wear, and even with that they work hard and they rarely last more than 50,000 miles even when fastidiously maintained. With the front wheels off the ground, rock the wheels and feel for excessive free play. If the pins are dry then a good load of fresh grease may take up the slack, but if not then replacement will cost about £150 for both sides at a specialist, or about £40 in parts to DIY.

After that, check the lever arm dampers for signs of leakage (and ideally get the filler plugs out to check the quantity and type of oil in them). While body control won’t be as firm or immediate as a modern sports car, good dampers should still arrest any bouncing in a single up/down cycle. Telescopic damper conversion kits are common, especially for the rear units, and offer more modern-feeling road manners. Check the wishbone and location link bushes are in good condition.

At the rear, make the same checks of the dampers (whether original lever arm or aftermarket telescopics) and be sure that the shackles and shackle bushes are in good condition. The springs themselves can seize up from age and lack of use, and if very old can lose their spring and go flat – the leaf spring should have a definite curve in it and an MGB GT should sit level.

The steering is beautifully simple – an unassisted rack and pinion. The rack itself barely wears. It will be heavy, especially at low speeds, but should be smooth and accurate once on the move. Stiffness or binding spots are more likely to be due to ungreased kingpins than any issues with the steering itself. Any MGB should exhibit good stability and roadholding – if it’s wandering all over the road or there’s any shimmying through the wheel then look for worn kingpins, tired wheel bearings or sloppy steering joints. Clonks and knocks going over bumps will usually be worn out anti-roll bar mounts (accompanied by a mild kicking at the wheel if it’s the front bar that’s that issue).

The MGB GT always had front disc brakes and rear drums, with a servo optional from 1970 and standard from 1973. Upgrades in the shape of bigger front discs or adapting the rears to discs as well are widely available but superfluous so long as you’re sticking with the standard power output and the original system is in good condition. Be sure the brake fluid is clean and up to the correct mark. Feel for sponginess or ‘pumping up’ at the pedal, pointing to worn master cylinder seals. Look for signs of leaking brake fluid at the back of the wheels, especially on the rears of little-used cars where the cylinder seals and dust rubbers can perish. Look at the discs for signs of scoring, wear or excessive rust (again a sign of a car standing with little use). Drumming or vibration through the pedal points to warped or rusted discs. None of these issues are difficult to fix but a full rebuild of the brake system will run to several hundred pounds.

Interior, trim & electrics

The interior of the MGB GT developed a fair bit through its life, from the simple black leather and crackle-paint dashboard of the early examples to the 1970s glory of the last of the line with the deckchair seats and plastic dashboard. In general the later interior’s aren’t as durable as the earlier ones, both in terms of the materials and the switchgear. A full new set of seat covers and carpets for a GT will be around £800 for the most common mid-period vinyl. The vibrant but fragile synthetic seat fabrics of the mid-1970s are more expensive so you really want to see these in good condition.

The chrome bumpers and grille of the original MGB GT remain the most popular, and it’s common to find later cars that have been cosmetically back-dated to this appearance, with rubber bumper cars also receiving the lower suspension height. Converted cars only really gain the value of the genuine article if they are period-correct in all respects, while most are something of a mix of old and new, which is no bad thing from a useability point of view and many owners like combining the exterior looks of the pre-1970 cars with the better gearbox, standard overdrive, more user-friendly heater controls and servo-assisted brakes of the later ones. Be sure that whatever chrome is carried by the car you’re looking at is in good condition as re-chroming a car with plated bumpers, grille, headlamps bezels and bodywork beading can become expensive.

No MGB had much in the way of electrics. An alternator was fitted from 1968 and the old double six-volt batteries were replaced by a single 12-volt battery in 1974, both of which are desirable features for cars that will see a lot of use. As is typical with British classics of era, most electrical gremlins are caused by bad earths at the components themselves rather than in the wiring and the system is rather under-fused. Check that any equipment fitted works as it should, that there’s no ‘leakage’ from one circuit to another (especially prevalent on the rear lights/indicators) and the wiring loom is in good condition. Be sure that the wiring insulation hasn’t gone brittle and that it’s not a mess of odd-coloured wire and Scotch Locks.

MGB GT: our verdict

The MGB GT ticks all the same boxes that it did in 1965 – few other cars combine classic sporting character with such everyday usability. The added bonus is that the MGB is now probably better supported in terms of parts, knowledge and specialist expertise than it was when it was in production. The sheer number of GTs still around, and the lingering image problem of the later rubber bumper examples perhaps creates a certain prejudice that prevents us from recognising what a great all-rounder the model really is. It’s been said that had the MGB GT been built in Italy and only 50 had been made it would be one of the most desirable classics in the world on the strength of its styling alone – it’s only because it was built in Abingdon and they made 125,000 of them that it seems so ordinary.

That does at least pay dividends when it comes to values. The once-yawning chasm between chrome and rubber bumper cars has closed significantly over the past decade but overall any MGB GT still offers great value for money and a very accessible means of classic motoring. GTs are still tracking at a little less than equivalent roadsters. Solid, average but usable late rubber bumper GTs can still be had for £3000-4000 or so, and even the very best, original low-mileage examples of these will not breach the £8000 mark. At the other end, pre-1970 chrome grille/bumper GTs can go for £15,000 if they are restored to extremely high standards and to original specification. Less exceptional but still excellent cars come in at £12,000, good but average ones at £8000-10,000 and anything up for less than £5000 is best treated as a project. The 1970-1974 cars fill in the gaps between those values, with a budget of £6000-8000 being perfect to pick up a very good but entirely useable example.

MGB timeline

1965

The MGB GT is announced in October at the London Motor Show, with sales beginning in the 1966 model year.

1967

The Mk2 MGB is introduced, featuring a four-synchro gearbox and a three-speed automatic gearbox as an option. Other changes include the fitting of two-speed windscreen wipers, an alternator with negative-earth electrics and reversing lights as standard.

1970

Alloy bonnet replaced by steel and leather seats replaced by vinyl upholstery. Chrome grille replaced by black-painted recessed type. Rubber inserts fitted to bumper overriders. Rostyle wheels become the standard fitment with wire wheels now optional. British Leyland badges fitted on front wings just ahead of the doors and italic ‘BGT’ tailgate badge introduced. New colour palette with bolder, brighter colours launched. Head restraints and a brake servo become optional extras.

1972

Dashboard modified with twin fresh air vents in centre and a transmission tunnel console with hinged armrest added to interior.

1973

Original-style grille reintroduced but with black honeycomb rather than chrome slats. Engine colour changes from maroon to black. In August the automatic transmission option is discontinued and the brake servo is now standard, as are hazard lights.

1974

September sees the introduction of the rubber-faced ‘5mph impact bumpers’ to comply with American legislation. Ride height increased by 1.5 inches. Collapsible steering column fitted. Single 12-volt battery replaces previous twin 6-volt batteries.

1976

GT badges fitted to rear quarter pillars to hide the roof/pillar joint which had been lead-loaded up to that point.

1977

Significant alterations made to the MGB GT: Uprated front anti-roll bar fitted, and rear anti-roll bar fitted for the first time to restore handling to similar level to pre-1974 cars. New high-flow radiator mounted further forward with separate expansion tank and electric fan. Tinted glass becomes standard on GT. New seats with nylon ‘deckchair pattern’ cloth introduced. Dashboard altered with plastic fascia, new instruments and layout, two-speed heater fan, four-spoke plastic steering wheel and new door cards incorporating radio speakers.

1980

MGB ‘LE’ models built, including 580 GTs in Pewter metallic grey with unique alloy wheels and side graphics, plus front air dam and new red/silver MG badges. These are the last MGBs built. Total MGB GT production is 125,323.