The Triumph Herald and its Vitesse counterpart were examples of how keeping it simple can work wonders. Here’s how to buy one

In the late 50s, Standard-Triumph found itself in something of a tricky position. The firm desperately needed to replace the ageing Standard 8 and 10 models with a new, modern small car, but was facing competition in the marketplace from the mighty BMC – not just for sales but for the attentions of suppliers, too.

Standard-Triumph had traditionally used bodywork supplier Fisher & Ludlow, but when the firm was acquired by BMC in 1953, clearly the Coventry firm was in danger of exposing its entire future model range to a competitor if it continued to work with the firm. Accordingly, they turned to Pressed Steel, but they lacked the spare capacity to produce bodies in quantity. That left only the smaller body makers which individually weren’t big enough to supply large quantities of monocoque shells.

The solution – born of necessity but one of the reasons these cars have survived in decent numbers – was to make the backwards step from monocoque to separate chassis. The brainchild of Standard-Triumph chief engineer Harry Webster, this allowed smaller bodybuilders not up to the challenge of making monocoque shells to provide the simpler bodywork and panels required.

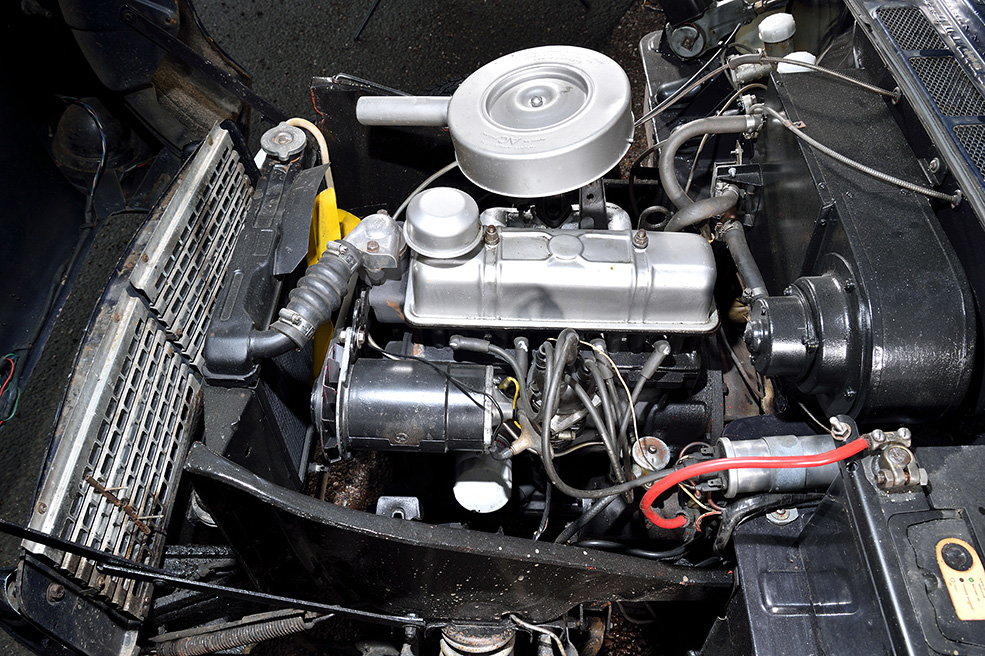

Styling the new body was another issue for Triumph, since none of the in-house proposals were deemed to be suitable. This led Webster to the door of Italian stylist Giovanni Michelotti who styled the sharp-looking car and thus began a long relationship with Triumph. Back in Coventry the Triumph designers did make one crucial alteration though: they added the car’s trademark forward-hinged bonnet and front end assembly which makes maintenance so easy. Under this flip front was to be found the 948cc four-cylinder as previously used in the Standard 10, good for 35bhp.

The new car featured independent rear suspension courtesy of a simple swing-axle set-up with telescopic dampers and leaf springs running transversely in a similar arrangement to the Spitfire and GT6. The front end was suspended by coil springs, wishbones and telescopic dampers.

The car was developed under the codename Zobo and christened Triumph Herald, launched in 1959 as a saloon, with the convertible appearing in March 1960 complete with a twin-carbed version of the 948cc motor which was subsequently offered in the saloon from February 1961 as the Herald S. In April 1961 the Standard motor was taken out to 1147cc for the ‘1200’ model, giving 40bhp and raising top speed to 75mph. An estate model was added in May 1961 and disc brakes were offered as an option from October.

In March 1963, the Triumph Herald 12/50 appeared, in saloon form only and boasting a heady 51bhp alongside other upgrades including revised gearbox, front discs, heater, screenwashers and restyled grille. The 12/50 was replaced in October 1967 by the 13/60, this time ditching the ancient Standard engine in favour of the new 1296cc pushrod motor as developed for the Triumph 1300 saloon. With 61bhp on tap, it was good for over 80mph complete with improved interior.

It may have been quicker than the cooking Heralds but the 12/50 was still not exactly a sports car, which lends some credibility to the story that the Vitesse was born from Harry Webster’s personal desire for a faster version capable of cruising the new M1 motorway. The development workshops craned a Standard six-cylinder engine into a Herald coupe and the result attracted a favourable response from the board, the idea of a more sporting Herald coupe or convertible receiving development priority over the four-door version of the car which had proved to be tricky to engineer.

Initially available as a 70bhp 1600cc unit – a six-pot engine this small being something of a novelty – the Vitesse received a rakish twin-headlamp front end to set it apart from the Herald.

In 1966, the Vitesse engine grew to 2 litres, sharing the powerplant with the 2000 saloon and the GT6, then in 1968 the Mk2 car turned up the wick to 104bhp in which form it was a 100mph car at last. Unsurprisingly, the lively swing-axle rear suspension was modified at the same time with double-jointed driveshafts, wishbones, relocated trailing arms and Rotoflex couplings. The Mk2 cars also received a revised grille and dashboard, plus Rostyle-look wheel trims and a silver painted rear number plate panel.

Incredibly, the Triumph Herald lasted until 1970 (although some bodystyles carried on into 1971 for a few months), with the Vitesse ending production in 1971. For a ’50s car which was old-fashioned even at launch, this wasn’t bad going at all and in fact part of its chassis carried on underneath the Spitfire until 1980.

Today the Triumph Herald and Vitesse make very practical classics, their separate chassis construction and that flip-front design making them easy to work on at home. “There’s nothing you can’t do on them,” advises long-term Herald owner and Editor of our sister title Classics Monthly, Simon Goldsworthy who reckons the cars still stand up as an easy-to-own entry into the classic car experience.

In Mk2 form with the more powerful engine and revised rear suspension, the Vitesse is a brisk car too, with a superb sound especially with a performance exhaust. Here’s what you need to know.

Bodywork

These cars may have used a separate chassis but that didn’t stop them rotting. The outriggers which carry the weight of the body are critical, especially at the rear where they extend under the boot floor. Severe corrosion here can affect the radius arm mounts, compromising the axle location.

You’ll also want to check all the points on the chassis where the suspension and running gear are bolted in place.

The body mounting points are also critical for obvious reasons. The mounts behind the sills are harder to get to, but on the plus side, the sills aren’t structural like they are on so many cars.

Chassis repair sections including perimeter rails and outriggers are available and they’re not expensive, although repairs where the chassis rails curve up around the differential will need fabricating. To do the job properly will entail removing the body which isn’t too tricky but can get expensive when you discover all the other repair jobs which are suddenly worth doing at the same time…

If the doors are sagging, suspect a rotten A-pillar but repairing this can get labour intensive. Elsewhere, the front end can be tricky to align properly, and wing bottoms can get crusty, especially on the convertibles where water runs down the B-pillar and they rot from the inside out.

Repair sections for the lower edges of the front end are available and door skins are also available new but those familiar with these cars advise against spending too much time and effort trying to achieve perfect panel gaps. The way these cars were constructed means they simply weren’t that precise when brand new. Indeed, even the cars in period press photos don’t boast perfect panel gaps. Note that Herald body and chassis parts were changed in May 1962 and the two versions are not interchangeable.

If you’re looking at a convertible, check that it’s an original factory-produced example, as the bolt-on nature of the roof means there are plenty of conversions around. A genuine convertible will have a commission plate with the letters CV, while a saloon will be DL.

Engine and transmission

With both four and six-cylinder engines check for bottom end noise and for good oil pressure if there’s a gauge fitted. A common Triumph issue from this era was crankshaft end float, so have an assistant push the clutch pedal while you watch the front pulley – anything more than minimum movement needs attention. Catch it early enough and it’s simply a question of replacing the thrust washers but if ignored, the thrust washers can fall out and then the crank will be running against the block, rendering it scrap.

Blue smoke on the overrun indicates valve guide issues, while smoking under power means piston ring issues. On the other hand, these aren’t expensive engines to rebuild and there are also used items around for the more common models.

The Vitesse engine tends to exhibit some timing chain rattle, but is generally pretty robust. The 1600 can sometimes suffer from detonation since they were designed to use high-octane fuels but this shouldn’t be too pronounced and using higher-octane Super Unleaded can often cure it.

All the gearboxes are generally reliable and a car which jumps out of reverse may simply need the linkage adjusting. If the shift action seems unduly sloppy, Triumph specialists can supply a bush kit to tighten it up again.

Overdrive was standard on the Vitesse and optional on the Herald. It’s electrically operated so if it doesn’t engage, then suspect a simple wiring problem.

The Herald and 1600 Vitesse used a non-synchro first gear, with an all-synchro box fitted to the Mk2 Vitesse. Although the gearbox was strengthened for the Vitesse, the synchromesh does tend to get weak with age on all these cars – especially on second – so learn to double-declutch your way around it.

The Herald and Vitesse benefit from simple running gear, and anybody with a modicum of mechanical aptitude should be able to keep one in fine fettle armed only with a Haynes manual and a selection of hand tools. Access is generally superb, too; with the large combined bonnet and front wing assembly raised up, you can even sit in comfort on the front tyre while fiddling in the engine bay. Gearboxes can be accessed from inside the car once you’ve taken out the removable tunnel, and can also be taken out that way should you need to change a clutch.

Triumph specified routine maintenance tasks for 6000 miles/six–month intervals and 12,000 miles/12–month intervals, but most owners these days will get by with a single annual service.

Steering, suspension and brakes

The swing-axle rear comes with its own reputation but to be fair you do have to drive the car pretty hard for the dreaded camber change and wheel-tuck to become an issue. Having said that, many Herald owners report that retrofitting the ‘swing spring’ as fitted to the later Mk4 and 1500 Spitfire will make a big difference to the feel of the car and reduce the camber change. Many Vitesse owners also report useful improvements from replacing the rear lever arm dampers with telescopics.

At the front end, the main issue is regular greasing of the trunnions. It’s due every 2000–3000 miles and if it does get skipped then the results can be dangerous. If the steering feels sloppy then it’s often likely to need just a simple set of column bushes, while polyurethane rack mounting bushes can sharpen things up even further.

The Vitesse has standard discs on the front and apart from issues like leaks, perished flexi-hoses and seized callipers if cars have been stood around, it’s all very conventional and for the most part reliable. With the Herald’s all-round drums you’ll want to check for leaky wheel cylinders. Brake hoses and pipes should be examined regularly, not because they are particularly prone to failure but because Heralds only had single-circuit brakes, so a single fluid leak that goes unchecked will take them all out.

Any service should include attention to grease points, though just how many will vary from car to car as things like UJs and track rod ends may be sealed for life or contain grease nipples. One critical point to remember is that while the trunnions on the rear suspension take grease, those on the front suspension must be lubricated with Hypoid oil instead.

Interior and trim

Thanks to specialists like Newton Commercial, there’s virtually nothing you can’t buy for the interior. Seat diaphragms, foams and straps are all available alongside cover sets in the original colours and patterns, while proper moulded carpet sets are also available. Door cards and rear quarter trims are also available in the original colours for both saloon and convertible, as are headlining kits.

It can get expensive to do the entire car though and professionally re-veneering a scruffy wooden dashboard can be an expensive job, so consider the state of the inside carefully, especially on convertibles where weather has taken its toll.

Some interior parts can be harder to source, however. Not many people realise, for example, that the 948cc cars had a compressed fibreboard dash painted black with grey flecks rather than a wooden plank, that the switchgear was grey and the dial faces white rather than the black of later cars.

Triumph Herald and Vitesse: our verdict

It might have moved away from the trends of the time via its separate-chassis layout, but there was little else dated about the Herald when it made its debut. It was a stylish, modern and very practical car when launched in 1959; Six decades on, its unusual pairing of style and practicality is virtually unrivalled on the classic scene; and while it can for obvious reasons no longer be described as modern, it is surprisingly easy to jump out of your daily driver and into a Herald with the minimum of mental adjustment.

This great looking saloon provided practical, economical family transport and nowadays is still a great choice. With oodles of charm and charisma, it’s a likeable and interesting alternative to a Ford Anglia, Austin A40 and others of that ilk, while the six-cylinder Vitesse is an entertaining and decently quick sports saloon (or four-seater convertible) for keener drivers.

Whether you opt for a Herald or a Vitesse, you’ll enjoy all the usual classic Triumph benefits, including one of the most vibrant club scenes in the UK, as well as superb back-up from a plethora of independent specialists when it comes to parts and upgrades. With values steadily rising, perhaps now is the ideal time to join the Herald-based family?

Triumph Herald and Vitesse timeline

1959

Triumph Herald launched in April as saloon and coupe

1960

Triumph Herald convertible arrives

1961

Herald 1200 introduced

Estate variant arrives

1962

Courier van variant introduced

Triumph Vitesse introduced

1963

12/50 arrives with 51bhp 1200cc engine, folding sunroof, Vitesse front brakes and a mesh grille

Herald 1200 gets 48bhp engine upgrade

1964

Courier and coupe production ends; Courier continues in knock-down kit form in Malta until 1966

1966

Vitesse engine grows to two litres

1967

13/60 arrives with 61bhp 1300cc engine and Vitesse-style bonnet.

Vitesse Mk2 arrives

1970

Saloon production ends

Triumph Toledo introduced as Herald replacement

1971

Herald estate and convertible production ends