When a manufacturer borrows a powerplant from another company to create a new model variant, it can often lead to greatness

Sometimes a car maker is unable to build a powerplant for its latest model, whether because of budget constraints, manufacturing limitations, or simply because another firm’s engine offers a neat shortcut to more prestige and power for a halo model.

Over the years, we’ve seen numerous deals being done to fit engines sourced from other companies and often entirely unrelated models, resulting in some truly unusual and special cars. Some have gone on to become highly desirable, while others have remained a little more under the radar. Here, we pay tribute to some of the most notable.

Sunbeam Tiger

The pretty Sunbeam Alpine had proved popular with European buyers as an MG alternative, but its underpowered 1.5-litre engine limited its appeal for the American buyers that Rootes was keen to gain popularity with. Negotiations took place with Ferrari for the Italian company to tune the standard four-pot and allow Sunbeam to stick a ‘tuned by Ferrari’ badge on the back, but talks ultimately never progressed further.

Instead, moves were made to endow the Alpine with V8 power, in a similar vein to the Carrol Shelby-driven project that had turned the humble AC Ace into the monstrous Cobra. Stories vary as to whether the initial idea came from race ace Jack Brabham or Ian Garrad, then the West Coast Sales Manager of Rootes American Motors, but ultimately it wouldn’t be long before work got underway.

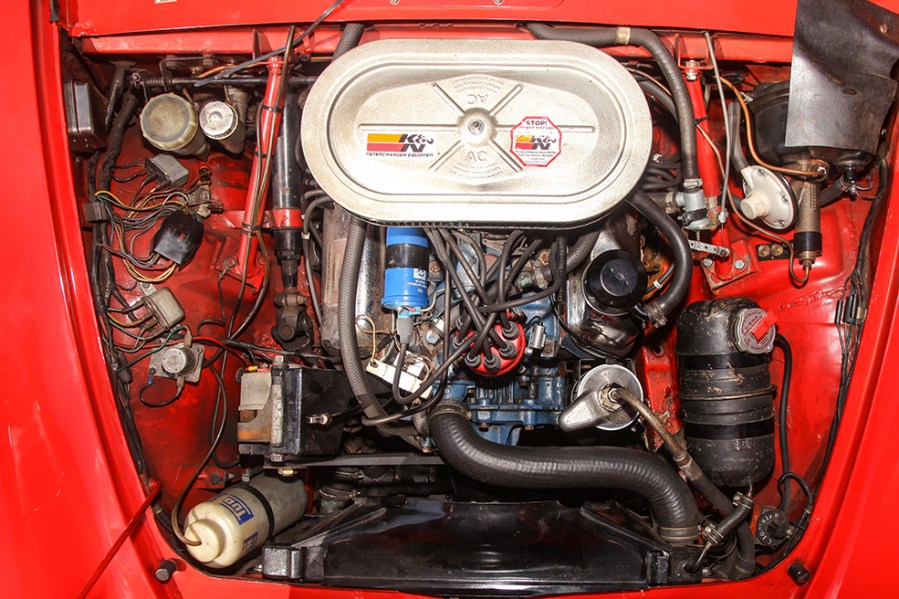

After some very rough eyeballing, the Ford 260 cubic inch (4.3-litre) V8 looked about the right size for the Alpine’s engine bay, as well as being a proven, reliable and powerful unit. Garrad, who conveniently lived close to Shelby American, asked Shelby for an idea of the timescale and cost to build a prototype, which was quoted as eight weeks and $10,000. While the project got underway, an impatient Garrad commissioned racer and fabricator, Ken Miles, to knock up a ‘quick and dirty’ prototype.

Provided with an $800 budget, a Series 2 Alpine and a used Ford V8, Miles produced a driveable V8 Alpine in just a week, proving the concept. By mid-1963, Shelby’s more refined prototype was complete, and when Lord Rootes drove it, he immediately ordered 3000 Ford engines. Jensen was then contracted to build what became known as the Sunbeam Tiger, after Ford insisted it wasn’t built Stateside for fear of compromising its relationship with Shelby.

Producing 164bhp, the Tiger was capable of 120mph and could sprint to 60 mph in 8.6 seconds – monstrous figures for such a diminutive car. Stiffer front springs supported the heavier V8 engine and a Panhard rod located the rear axle, but the rest remained unchanged over the Alpine, save for ‘V8’ and ‘Tiger’ badging. It lacked the dainty handling of the Alpine, but for point-and-squirt performance and excitement, the Tiger was in a class of its own in Europe. The epic soundtrack and muscular performance found favour Stateside too, where almost 97 per cent of 1964 Tigers were sold.

Approximately 3763 Mk1 Tigers were built between April 1964 and August 1965 before some mild revisions – these cars termed Mk1A. The Mk2 of 1966 received an upgraded engine; a 4.7-litre 289 cubic inch V8 over the previous 260 cubic inch version. For a time the two coexisted, but Sunbeam Tiger production was not long for this world. In 1967 the final car was built, with its demise brought about by the takeover of the struggling Rootes Group by Chrysler. In all, just over 7000 were produced and you’ll usually have to pay more than £40,000 to buy one today.

Fiat Dino

Ferrari’s motorsport efforts were booming in the early 1960s, but if it wanted to satisfy the new rules for Formula Two racing due to commence from 1967, it would need to homologate its V6 racing engine.

The power units now had to be production-derived and be built to the tune of at least 500 units within 12 months, but Ferrari didn’t have the manufacturing capacity to develop and sell that many engines in a year, so an agreement was reached with Fiat whereby it would be responsible for getting them built and out the door in a new model.

Named in honour of Enzo Ferrari’s late son, Alfredo (whose nickname was Dino), the Dino V6 was a 2.0-litre unit with a 65-degree V-angle. Conversion of this racing engine for road use and series production was entrusted to the engineer Aurelio Lampredi, but to avoid inconsistent engine supply, Fiat insisted on building the V6 in-house, much to the frustration of Enzo Ferrari.

Although also destined for the Ferrari Dino 206 and 246, Fiat’s more mass-produced home for the engine was no less worthy. The Fiat Dino was introduced as a two-seater Spider at the Turin Motor Show in October 1966, before a two-door Coupe version with a longer wheelbase was revealed at the Geneva Motor Show in March 1967. This Spider was the work of Pininfarina, while the Coupe was initially by Bertone’s Giorgetto Giugiaro, before Marcello Gandini finished the job.

Mating the V6 to a five-speed manual gearbox, the Fiat was a gem to drive and for many, deserved to wear a prancing horse on the nose. Curiously, Fiat quoted 158bhp for its car, while Ferrari claimed the Dino 206GT made 180bhp, despite it using the same engine, that was built on the same production line…

Today, the Fiat Dino is held in similar regard to contemporary Ferraris, with coupes rarely selling below £40,000 and Spiders often changing hands for over £100,000. That said, consider that the same engine in a less practical Ferrari body will set you back £350,000, and suddenly that sounds like good value.

Porsche 924

With Volkswagen wanting a flagship sports car and Porsche looking to replace the ageing 914 as its entry-level model, the two collaborated on what became Project 425, VW’s only strict caveat being that it must utilise an existing VW/Audi inline-four engine.

Porsche chose a rear-wheel drive layout and a rear-mounted transaxle, to help provide 48/52 weight distribution. The 1973 oil crisis led to Volkswagen getting cold feet and ultimately prioritising the Golf-based Scirocco instead, while Porsche – who was too far into development at this stage to back out, and needed that 914 successor – persevered with what became the 924. The deal would see it built at the ex-NSU factory in Neckarsulm, north of Porsche’s Stuttgart headquarters. Volkswagen employees would build the cars under Porsche supervision, while Porsche would own the sharp Harm Lagaay design.

Beneath the smart profile and distinctive wraparound glass hatch, the 924 did indeed use a VW/Audi engine, the 2.0-litre four-pot EA831, as first used in the Audi 100 and then the Volkswagen LT van. With Bosch K-Jetronic fuel injection over the LT’s carburettor and a Porsche-specific cylinder head, the 924 produced 123bhp in European guise, enough for a reasonable 0-60mph time of 8.5 seconds – surprising given the 924’s frequent criticism of lacklustre performance.

While not a tuneful nor exciting lump, the EA831 not only returned excellent fuel economy and flawless reliability, but parts support was excellent given the unit’s humble origins, and even today, maintaining a 924’s engine is a simple task.

The 924 borrows heavily from Volkswagen’s parts bin in other areas, making replacing the likes of CV joints, steering racks and brake cylinders easy and relatively cheap. The subsequent 170bhp 924 Turbo and 2.5-litre 924S (an engine sourced from its 944 big brother) would add kudos to the model, but there’s something quite charming about a basic early 924. They’re not bargain-basement cars anymore though – good ones start from around £7500.

Lancia Thema 8.32

Part of the Type 4 project that also yielded the Saab 9000, Fiat Croma and Alfa Romeo 164, the Lancia Thema offered a wide range of engines that included everything from Fiat’s twin-cam to the Alfa Busso V6, but stood out primarily for its quirky cabin and Lancia charm, rather than anything specific. That is, until 1986. While Saab offered its rapid Turbo model, Lancia wanted a high-performance Thema with a touch of exotica about it, resulting in the Thema 8.32.

Under the bonnet of this fairly anonymous saloon was Ferrari’s Tipo F105L engine, a four-valve-per-cylinder V8 that had seen service in the Ferrari Mondial and 308 – hence the 8.32 name denoting eight cylinders and 32 valves. The supercar engine was tuned for use in a luxury saloon, with a cross-plane crankshaft replacing the typical flat-plane, smaller valves and a different firing order, plus a reduction of the bore and stroke to 91x71mm, giving a capacity of 2927cc. A new subframe fitted the V8 into the Thema’s engine bay surprisingly neatly, helped by the V8 also being used transversely in the Ferrari.

The result was a ferocious 215bhp and 0-60mph in 6.8 seconds on the way to 149mph, all accompanied by a true Ferrari howl that you’d never believe was coming out of a saloon car. Remarkably, this was the most powerful front-wheel drive car in the world at the time, but it was a bit of a sleeper. You got an 8.32 badge and subtle Ferrari badging on the bootlid and engine, but otherwise there was only five-spoke wheels and an electronically adjustable rear spoiler to mark the hot Thema aside.

It received Enzo’s blessing when Mr Ferrari himself bought an 8.32 to use personally, while journalists favourably compared it with the likes of the BMW M535i, Lotus Carlton and Ford Sierra Cosworth. Ferrari power in a front-wheel drive luxury saloon meant the handling could be a bit unpredictable, but the performance, soundtrack, excitement and cachet of the engine were unrivalled. It’s small wonder the Thema 8.32 is a £30,000 collectible today.

Lotus Elise

When Lotus sought to launch an all-new driver’s sports car to turn its fortunes in the 1990s, it had to face the reality that it didn’t have an in-house engine to suit – while the 900-series units were still in production, they were too big both in capacity and physical size to fit the new Lotus Elise. Accordingly, it approached Rover to strike a deal on the 1.8-litre K-Series.

Despite its origins, the K-Series almost feels like it could’ve been a Lotus engine from the outset – it focused on light weight and minimal friction, as well as boasting a revvy nature and high power output for its size. The four-pot suited the lightweight roadster perfectly, encouraging enthusiastic driving to get the most from it, while still possessing enough low-down power to be tractable.

What’s more, the K-Series seemed happier in a Lotus than a Rover, with fewer head gasket failures. Indeed, it would prove to be remarkably reliable even when tuned, a blessing given the mid-mounted layout. Initially, the engine was used in 118bhp guise, but there were more powerful versions too, the Sport 190 track package upped thing to as much as 187bhp, while the 111S of 1999 featured the VVC unit and produced 143bhp.

The Rover K-Series wouldn’t be the only outsourced engine to find its way into the Elise – when Rover’s future looked uncertain in the mid-2000s, Lotus stopped using the K-Series for the S2 Elise and instead struck a deal with Toyota for its 1.8-litre 1ZZ-FE and 2ZZ-GE units. The former was offered in the Elise S and produced the same 134bhp as it did in the Mk3 MR2, while the latter produced 190bhp in the Elise R and made 148mph and 0-60mph in 4.9 seconds possible.

That wasn’t the end, however – the Elise SC gained a supercharger on the 2ZZ-GE, resulting in 217bhp and a 4.3-second 0-60mph time, as well as a blower whine to accompany the raspy four-pot. Durable, tuneable and economical, the Toyota units not only proved the perfect fit for the Elise, but were the ideal successors to the K-Series.

Rover 200 (R8)

Rover’s collaboration with Honda to create the 200/400 ‘R8’ and Concerto duo yielded fantastic results – a sharply-styled, practical, nimble-handling family car that was well-priced, safe and well-equipped. Broadening the appeal was a wide range of body styles: in addition to the 400 saloon and subsequent Tourer estate, the 200 would be available as a three- and five-door hatch, with later additions including the Coupe and Cabriolet.

However, the range of engines also helped to cement the R8’s success. As well as the new K-Series engine in 1.4-litre guise and Rover 2.0-litre T-Series, the car would make use of the 1.6-litre Honda D-Series in both single- and twin-cam form. In addition, Rover recognised the need for a diesel engine to appeal to both fleet buyers and the European market. However, it was also acknowledged that the Perkins Prima unit used in the Montego would not be appropriate, given its age and lack of power and refinement.

A deal was therefore struck with PSA for its critically acclaimed XUD diesel engine, a unit that was every bit as frugal as older Perkins units, but far more refined, quieter and more powerful. True, you wouldn’t mistake it for a petrol engine, but the XUD was a noticeable step-up over the Perkins Prima and offered all the attributes the key fleet and European markets were after.

A naturally aspirated 1.9-litre XUD9 was the cheaper diesel option for the R8, but the turbocharged 1.8-litre XUD7T was the favourite, combining an ample 87bhp with an impressive claimed 50.4mpg. It lacked the revvy character of the petrol engines, but those who opted for diesel wanted smooth, economical torque, and the XUD offered exactly that. Over 945,000 R8s sold, not accounting for the Honda Concertos that used the same engine. Of course, the wide range of engines means we can’t attribute all of the success to the XUD, but it played an important part.

MG ZT 260

Nobody could’ve imagined the results when MG Rover created performance variants of its worthy but uninspiring 25, 45 and 75 models. What resulted were the MG ZR, ZS and ZT respectively, and while the two smaller cars got all the attention for being fizzy driver’s cars, the ZT in both saloon and Tourer guise got on with being a suitably subtle gentleman’s express.

That is, until late-2002, when management decided that some halo models would lift the brand’s image, resulting in the ill-fated SV coupe, as well as a V8 being shoehorned into the 75 and ZT. Specifically, a Mustang engine – the 4.6-litre Ford Modular V8 as used in the Crown Victoria and ‘S197’ fifth generation of the iconic pony car.

Doing this would be outrageous enough, but MG Rover also opted to totally reengineer the 75’s neat-handling front-wheel drive chassis to make it rear-wheel drive. As part of a modest £30 million budget, Prodrive was commissioned to adapt the floorpan, resulting in a rear-driven chassis for what would be coined the MG ZT 260, after its 260bhp output.

The single-cam, two-valve-per-cylinder V8 wasn’t a sophisticated lump, but with 302lb.ft of torque and a lovely deep rumble, it gave the ZT shove and character in abundance. The performance was no-way shabby, with the 0-60mph dash over and done in 6.2 seconds before an electronic limiter pegged it back at 155mph.

Visually, some subtle badging, quad-pipes and unique wheels on the facelift cars is all that set the 260 apart, making it a true sleeper. However, 22mpg was all you could hope for and despite its hefty £28,000 price tag that put it squarely in-line with the BMW 330i, typical MG Rover rattles and dissolving trim weren’t uncommon.

The firmer springs and dampers required to support the heavy V8 and compose the handling meant the ZT 260 was no relaxed wafter, but responded well to aggressive driving. Obviously, this suited the sporting image of the MG rather more than the stately Rover 75.

It should come as no surprise that the expensive, thirsty, firm-riding MG ZT 260 was not a runaway success – just 720 MGs and 167 Rovers were built in total, and some attribute the costly project as part of MG Rover’s demise. However, consider the lunacy of investing tens of millions into shoehorning a Mustang V8 into a humble Rover 75-looking saloon, let alone the fact you can buy one from £7000, and you can’t help but love the ZT 260.