The Triumph TR7 is the best-driving and also the most affordable of all the TRs. Here’s how to buy one

The Triumph TR7 used to be considered something of a poor relation: frowned upon by traditionalist enthusiasts of the older TR models, it hadn’t been around quite long enough to gain classic status purely on account of its age, while Harris Mann’s edgy wedge was perhaps a reminder of the decade we were trying to forget as we forged ahead into the 80s and 90s.

Nowadays things have very much changed and while a TR5 might rumble past a group of teenagers without raising an eyebrow, a TR7 – especially a coupe in the striking Triton Green – will turn heads. In that respect the passage of time has been kind to the Triumph TR7, even if the BL-era build quality struggled to shrug off the effects of successive British winters.

In the opinion of many, it’s also the best-driving of all the TRs, the four-cylinder engine giving it handling balance the nose-heavy six-cylinder cars can’t match and its modern monocoque construction doing away with the separate chassis. We’ve taken some stick from TR6 owners in the past for that comment but there’s no arguing that the car’s underpinnings are quite literally from a different era with its MacPherson strut front end and four-linked rear axle.

You’ll also stumble against the suggestion that the Triumph TR7 isn’t a ‘proper’ TR, but in reality the car was designed very much as a continuation of the TR2-TR6 line – and despite its maker by then being part of British Leyland, the TR7 has the distinction of being the last car to be developed independently by Triumph. It’s also acceptably brisk and even the regular four-cylinder car offers pace to match a mid-90s GTI.

Codenamed Project Bullet, the TR7 was originally to have been part of a wider range including a four-seater coupe dubbed Lynx and a four-seater convertible in the Stag mould going by the name Broadside. Both of these made it to the pre-production stage, but were killed off amid the industrial unrest which plagued early Triumph TR7 production and BL’s dire finances at the time: with the need to concentrate on the volume cars, a niche market sports car range wasn’t something time and resources could be diverted to.

A similar fate befell the proposed Triumph TR7 Sprint, with less than 60 of these 16-valve 2-litre cars being assembled before the model was dropped. All of which meant that the TR7 range which made it into production comprised the regular 2-litre four-cylinder, using an enlarged version of the slant-four engine found in the Dolomite, plus the Rover V8-engined TR8. The V8 car was only marketed in left-hand drive form, with the majority going to the USA, although a very few right-hand drive examples did escape.

Such is the ease however with which a TR8 can be created using a Rover engine and all the factory-style parts that you could be forgiven for thinking that the TR8 was a popular seller in its homeland. Over the years, hundreds of ‘TR7 V8’ cars have been built, with engine options ranging from mild Land Rover tune to wild TVR power and if done well, it can be a glorious thing.

For now though, we’ll concentrate on the production models, which launched in January 1975… but only in the USA. Incredibly, UK buyers had to wait until May 1976 to get their hands on the new car, which was produced initially at the Speke facility on Merseyside. It was a troubled time for industrial relations within BL and newly installed head Michael Edwardes duly made good on his threat to close the plant if trouble didn’t stop, production moving from Speke to Canley in 1978. In August 1980, with the planned closure of the Canley manufacturing facility it would move again to the Rover site at Solihull, with production finally ending in October 1981.

The eagerly-awaited convertible was introduced in early 1979, once again in the USA before the UK, with right-hand drive deliveries beginning in early 1980.

Triumph TR7 changes during production were few and related mainly to cosmetics. The signature tartan seat and door trim was introduced in March 1977, while changes required for the convertible version were also applied to the coupe in the shape of repositioned interior lights and smaller fuel filler.

The TR8 also required double power bulges in the bonnet to clear the carburettors and this became standard fitment on all cars built in Canley and Solihull. The interior trim would change again with vinyl outers and tartan centres during Canley production and Solihull cars later received velour trim. The Solihull cars also received plastic badges on the bonnet instead of the adhesive laurel wreath graphic of the Canley cars.

As for the running gear, the car would retain the carburetted 1998cc ‘slant four’ engine throughout its life, producing 105bhp and 119lb.ft on twin SU HS6 carbs and driving initially through a four-speed box, with a five-speed fitted to the Canley and Solihull cars.

It was reckoned by BL at the time that over 200 detail improvements were made during the shift from Merseyside to Warwickshire, some of which include better weather sealing of the pop-up lamps, a hot air feed to the carburettor intakes, improved electrical system, revised cooling system and better rust protection.

Bodywork

With the youngest Triumph TR7 now a good few decades old and production having been carried out under BL, clearly structural rust will be the big issue. It’s thought that Canley and Solihull cars were better protected by the factory but there’s still plenty of scope for rot and unlike older TRs the unitary shell can’t be lifted off the chassis to make repair easier.

As usual, the sills are critical and on the TR7 they run behind the front wings, meaning that a quick repair with the dreaded ‘over sills’ may have left weakened rotten metal hiding in that critical area. If cover sills have been welded on to the outside, then lifting the carpets to check the inside can give a better idea of the car’s solidity, but since they were glued down originally this isn’t always possible.

Elsewhere, check the strut tops under the bonnet carefully and at the rear, examine the boot floor and spare wheel well.

All panel edges need a look, while rust between floor and sills will indicate problems and bubbling in the seam along the top of the rear wings can also be expensive to fix, as can rot in the joint between sill and rear wing. Inner arches can also let go, but less obvious is a corroded screen surround. This can get costly to repair but isn’t always obvious, and can cause other issues when it starts to leak. Check for bulging or distorted rubber seals and chrome inserts.

While inside the car, pull the carpet off the rear bulkhead if possible and look for stress cracks which can indicate rot where the trailing arms mount to the body. If in doubt, get underneath and have a look too.

Don’t be alarmed to see paint peeling off the headlamps as they’re aluminium so it’s a paint issue rather than rust. The good news is that although entire bodyshells are no longer available, repair panels are sold for most of the areas you might need to work on.

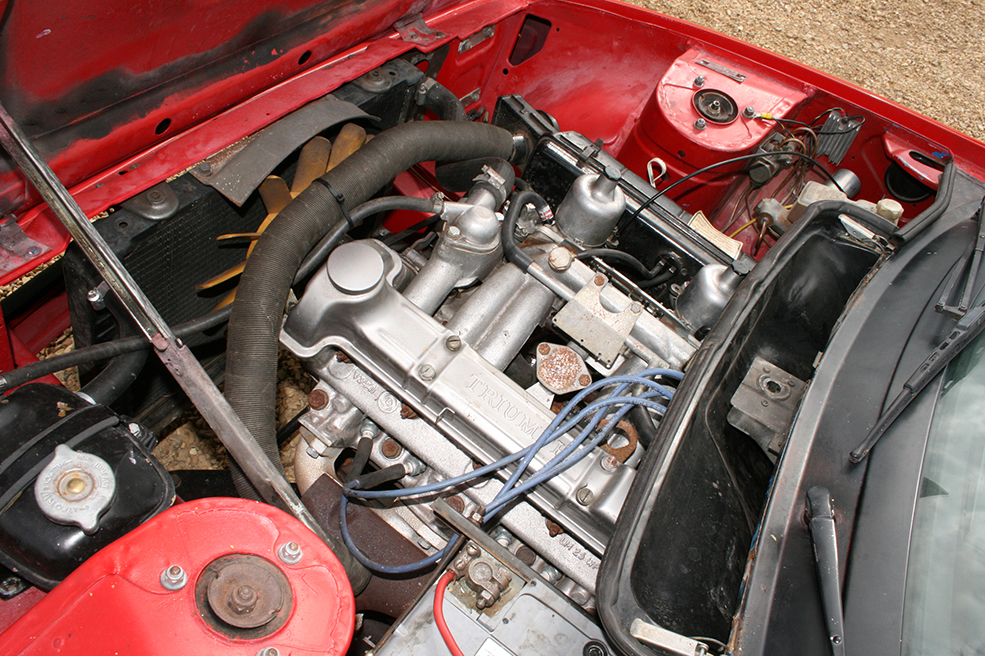

Engine and transmission

The slant-four Triumph motor is a well-known unit and generally pretty long lived when maintained properly. The stumbling block of course being that many weren’t looked after at all in the years when values were very low.

Aside from the obvious oil leaks which are common in any case, the biggest issue with the engine will be a warped cylinder head due to differential expansion between the iron block and alloy head – not helped if owners have neglected to keep up the anti-freeze concentration, vital for its corrosion-inhibiting properties. Before long this will manifest itself in head gasket issues and a serious problem will be easy to spot via the oil and water mixing. If the engine quickly starts to overheat when left idling after a run this can be a sign that all is not well in the head gasket department.

Although it’s not a complex engine by modern standards, head removal can be tricky thanks to the steel studs tending to corrode into the alloy head. They’re also fitted at an angle which makes removal of the head impossible with the studs in place.

Many owners will have fitted an electric fan as a preventative measure so don’t be suspicious of a car which has one fitted.

Elsewhere, timing chains can get noisy although they will carry on perfectly well for many miles but the factory’s recommended change interval was 25,000 miles.

In recent times, tricky-to-diagnose engine issues have been traced to water in the fuel, something encouraged by the location of the filler cap which tends to gather water in the recess. In time the problem will be bad enough for the tank to rust out and replacement involves dropping the rear axle.

Usefully, the TR7 engine was fitted with hardened valve seats from the factory, meaning the cars can run on unleaded fuels without additives.

On both four and five-speed boxes the synchromesh can become weak in old age but most owners simply live with it and the shift action will generally improve when the engine and gearbox are properly warm. Triumph specified automatic gearbox (ATF) fluid for these boxes which improves the shift quality.

Parts for the five-speed box are generally available through the usual specialists, while a clunk on hard acceleration can be nothing more sinister than a worn propshaft joint or simply the bushes in the trailing arm mounts.

Rear axles tend to be louder on five-speed cars but unless it’s outrageous don’t be too worried.

Suspension, steering and brakes

Over the years the TR7 has become known for a wheel wobble at speed, which has sometimes been put down to cheaper aftermarket steering racks. Otherwise, check the bushes throughout the front end and the condition of the brake discs which need to be mounted squarely to the hubs. Aftermarket wheels can also cause the issue if they’re not perfectly centred on the hub.

The TR7 is no Lotus admittedly, but should feel reasonably precise so if it seems baggy then you’re looking at replacing suspension bushes in stages until you sort it. Poly bushes are available for many locations which will make a big difference.

Interior

Being a Triumph, the supply of trim is excellent and Rimmers for example can supply door cards and seat trims in most colours apart from the garish tartan of the early cars. Budget on £350 a set. Carpets sets are also available to replace originals rotted out by all those water leaks and it’s an easy DIY way to massively improve a car’s appeal.

Don’t forget to view a convertible TR7 with the roof up! It isn’t a complex affair though and if it looks tatty it’s not the end of the world: specialists can supply a PVC outer cover or a full replacement mohair item. Frames can also be replaced separately if bent or damaged.

Triumph TR7: our verdict

As a classic today, the TR7 really comes into its own: parts support is simply superb thanks to the specialists and there’s precious little you can’t obtain. As for the choice of model, it’s no surprise to learn that the elegant convertible has survived in greater numbers than the coupe but there are plenty out there who prefer the hard-topped Seven simply for its looks and rarity means prices of the once-unloved coupes are now strong.

And if you want performance above all else, there’s always the option of a V8 – either in an official TR8, or one of the many engine-swapped examples.

Ignore the nay-sayers: the Triumph TR7 is a fine classic sports car that’s fun to drive, great to look at and relatively easy to fix. What’s not to like?