Stylish and capable, the Rover SD1 suffered from a poor reputation but if you’re after a big, comfortable British classic it’s a very appealing choice

Words: Chris Randall

Having become known for its rather fine saloons, including the stately P5 and innovative P6, Rover took rather a different path for its next executive car. The ‘Specialist Division 1’ had become a hatchback with its designer, David Bache, citing the Ferrari Daytona as a styling influence. In development since the early 1970s, the car was launched to an expectant public in 1976 and offered space and comfort in an affordable package.

The SD1 went head-to-head with rivals such as the Ford Granada, Citroën CX and Opel Senator as well as premium models like the W123 Mercedes-Benz and BMW 5 Series – all of which still form the main alternatives. Unfortunately, the big Rover soon gained a reputation for poor quality, reliability issues and a propensity for alarming amounts of rust, although it’s at least possible to get around such things today.

A sound range of four, six-cylinder and V8 engines and increasingly luxurious trim levels would be offered over the years, with the Series 2 of 1982 further improving the design and quality, plus there was the properly sporting Vitesse. By 1986 the 800 was waiting in the wings as the Rover SD1’s successor and production ended with 303,000 having been built.

Bodywork

The Rover SD1’s reputation for corrosion was well-founded, and it’s still pretty much the number one issue to be aware of today. Unless there’s a record (preferably photographic) of a top-notch restoration in the recent past, then you’ll want to spend plenty of time scrutinising the panels and structure. Start by checking the leading edge of the bonnet and the lower extremities of the tailgate and doors, before moving on to the front and rear wings – inner and outer – along with the wheelarches and sills.

The front and rear valances are worth checking for rust, and it’s worth taking a close look at the screen and sunroof surrounds for signs of bubbling as repairs here can become quite involved. We’d also recommend a thorough examination of the bulkhead area, and don’t forget to give the cabin and boot floors a thorough inspection.

Unless you’re looking at a car that’s beyond saving the encouraging news is that Rimmer Bros can supply a wide range of panels and repair sections, although with not everything available do your homework before you consider taking on a major restoration. Such a task can swallow an awful lot of time and money, especially if extensive fabrication is required.

Engine and transmission

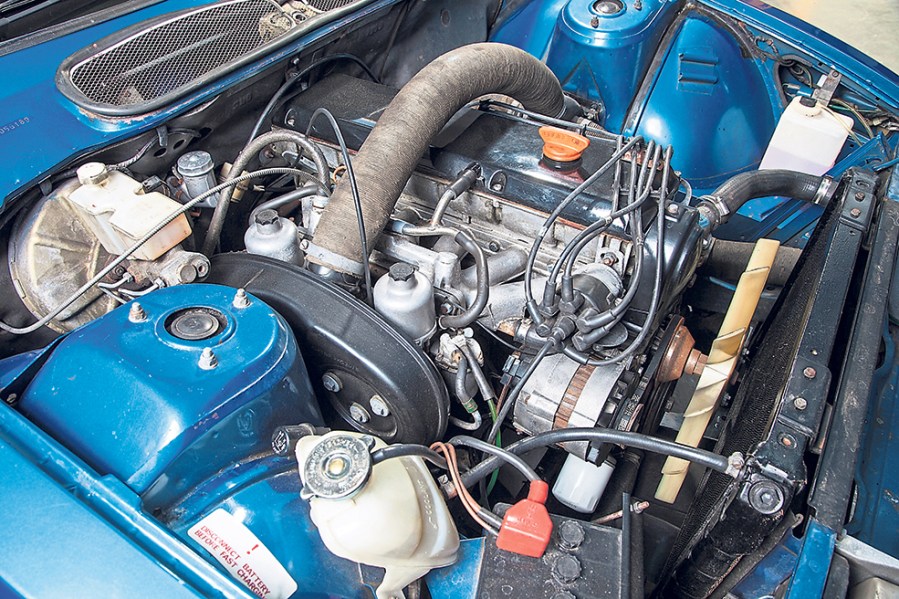

While the 2-litre petrol and 2.4-litre diesel models are perfectly capable, the limited parts availability means you’re better off turning to the six-cylinder 2300/2600 or 3500 V8. The six-pot Rover SD1 models are simple to maintain and have few inherent problems. The most serious is blockage of the camshaft oil feed which, should the shaft snap, will result in mechanical carnage; changing the oil and filter every 3000 miles will help avoid the issue. And if there’s no record of cam belt changes, that’s the first job to carry out. Poor running could be due to carburettors in need of an overhaul but that’s not a difficult job.

As for the V8, its use in so many cars means there’s no end of knowledge out there, and you won’t have any trouble sourcing parts. Assuming there’s no sign of normal wear and tear, such as burning oil or knocks and rumbles, then the key points to watch for are lack of oil changes leading to camshaft wear and sludged hydraulic tappets, any oil and coolant leaks, plus any signs of overheating that will compromise the head gaskets. Fuelling was by carburettors or Lucas fuel injection, and it’s the latter that needs more careful inspection – ECU problems can lead to poor running and specialist attention will be needed. If you’re looking at a complete rebuild then expect to pay £3000–4000 for any of the engines.

Transmission-wise, the LT77 five-speed manual is pretty robust so you’re really just listening for whining bearings and the crunch of ailing synchromesh. A specialist rebuild is around £600 with a reconditioned unit costing £1000 or so. The latter is similar for the three-speed automatic, although rebuilding one is a little costlier, and it’s mainly a case of ensuring that it shifts ratios promptly and doesn’t thump into gear. A whining differential rarely fails completely but oil leaks from the axle are a common issue, and should the worst happen you’re looking at around £900 for a reconditioned one.

Suspension, steering and brakes

The Rover SD1’s suspension comprised MacPherson struts up front and a live axle with coil springs and telescopic dampers at the rear, with the Vitesse getting a lower, stiffer set-up. Replacing tired parts isn’t prohibitively expensive, but the original Boge self-levelling units fitted at the rear aren’t available so you’ll need to convert to a conventional arrangement; heavy-duty dampers and springs are often the best bet but you may need to experiment to find the set-up that suits you. Renewing all of the bushes will be time consuming and could rack up a hefty labour bill, but if you can tackle it yourself then a complete kit is £130 or so with polyurethane items about twice that. Lastly, it’s well worth checking for any signs of corrosion around mounting points, especially at the rear trailing arms where rot can make a bit of a mess.

Brakes were a straightforward arrangement of discs and drums, with the Vitesse getting uprated ventilated items at the front. Wear and neglect will be the main problems, so check that everything’s in order, and just watch for leaking rear wheel cylinders and corroded or seized calipers. Parts are inexpensive and easy to source, and if you’re considering a Vitesse it’s worth uprating the front discs and pads for improved stopping ability.

The rack and pinion steering should feel accurate on the road, so anything else will need investigation. Worn ball joints are easy and cheap to replace but if the rack itself is worn then budget around £400 for a reconditioned item. Most examples will have power assistance, and it’s a case of checking for fluid leaks and for a worn pump. Lastly, where alloy wheels are fitted give them a thorough check for corrosion or damage – refurbishment is around £75–80 per corner.

Interior and trim

Don’t underestimate the importance of finding a Rover SD1 with a good interior. It’s particularly important for the Series 1 where the trim wasn’t very robust and is now extremely hard to find. Plenty of trim sections were constructed from cardboard, and once damp got in it wasn’t long before it started to disintegrate. That includes the backing for the headlining but Aldridge Trimming sell a fully-trimmed fibreglass board for £354. Damage to the dashboard and instrument binnacle will prove a real headache when it comes to tracking down replacement bits, too.

The Series 2 wasn’t always a great deal better, so a really decrepit cabin really is best avoided. In any case, you’ll want to check for threadbare carpets (leaking windscreens ruined them) and seat trim – sourcing the material for models like the V8-S is nigh-on impossible, and it’s easier to repair or replace leather. Extensive use of wood and hide arrived with the Series 2 when interiors became more traditional, and Vanden Plas models really did feel very luxurious, but the costs of major professional re-trimming will soon mount.

Electrics were never a Rover SD1 strong point so it’s going to be a case of systematically checking that all of the gauges, switchgear and warning lights operate as they should. Conscientious scrutiny is even more important on more lavishly-equipped models, where you’ll have the likes of electric windows and mirrors, central locking and air-conditioning. With time and patience you can eradicate many of the niggling problems, but be prepared to learn to live with the odd random fault.

Rover SD1: our verdict

It became fashionable to simply dismiss the Rover SD1 as an unreliable, rust-prone money pit, and while such a reputation wasn’t entirely undeserved the passing of time means it can be viewed more kindly. OK, so buying one needs care if you want to avoid a wallet-wilting restoration but find a cherished, well-maintained example and you’ll discover the big Rover to be a very enjoyable proposition. V8s in particular blend luxury and performance in a way that’s mighty appealing, although don’t consider the six-cylinder models as poor relations as they are more than capable.

A good Rover SD1 will more than hold its own when compared to the rivals mentioned earlier on, and when it comes to ownership the excellent club and specialist support and a generally good supply of parts are real pluses. Not to mention the fact that relative mechanical simplicity means there’s little to fear for the competent DIY mechanic.

Values of these big Rovers have been rising but you still don’t need to break the bank to get your hands on a nice, usable example. Even at a couple of thousand pounds you’re in project territory where a bit of caution is needed, but closer to £5000 should bag a six-cylinder car in nice condition, or a V8 that requires a bit of ongoing fettling. Double that budget and you’ll get an excellent V8 with a few thousand more needed for a nice Vitesse. It’s the Twin Plenum versions of the latter that are in most demand, and the very best of those can command in excess of £20,000.

As for the 2-litre and diesel variants, they’re rarer but fetch broadly similar money to the six-cylinder cars. It’s tempting to just focus on the V8s and while they do add extra appeal you certainly shouldn’t dismiss the 2300/2600. Prices are more accessible and if you find one that’s been cherished it’ll prove a more than satisfying ownership proposition.