The Elan M100 may not have been a sales success but it certainly didn’t lack for talent. Here’s how to buy a great example

Words: Chris Randall

When Lotus wanted to introduce a model that sat beneath the likes of the Esprit they decided on a re-boot of the Elan name. But there was a surprise for the marque faithful, with the new wedge-shaped design adopting a front-wheel drive layout. It was a decision some traditionalists struggled to accept, but in practice the handling was superb and remains a high-point of Elan M100 ownership today.

Launched in 1989, the Series 1 was offered in normally-aspirated or turbocharged form, although the modest price difference ensured most plumped for the latter. Clothed in a body designed by Peter Stevens, there was a lot to like about the new Lotus even if a rival in the shape of the Mazda MX-5 arguably contributed to limited sales. Just 3855 – and only 129 non-turbo cars – were built before production ended in 1992, but it would restart a couple of years later under Bugatti ownership; essentially a way of using up remaining engines, 800 Series 2 cars were made up to 1995.

In an unlikely move, Kia bought the M100 tooling and continued production for a few more years with its own 1.8-litre engine, but these were never sold in Europe. Fast-forward the best part of three decades and the M100 Elan remains sought after today, and with good reason.

Bodywork

The usual caveats apply to the M100’s GRP bodywork, and while it’s not prone to cracks or crazing, spend time examining the panels for damage or ham-fisted attempts at repair. Specialist skills are need to do a good job, which doesn’t come cheap, and while replacement body sections are available they are predictably expensive. Panels were either bolted or bonded in place depending on location, and gaps between them were pretty tight – anything noticeably awry could indicate previous accident damage. It’s also worth checking for stone chips around the front end (and resulting paint rectification) and faded paintwork; red cars tended to be more affected by the latter with a full respray the only answer.

Of greater importance is the condition of the steel chassis. which was Dinitrol treated when new. This protection should have been topped-up periodically but, if missed, the result could be extensive corrosion. A specialist we spoke to said it tends to affect the rear section so look for repairs, but he also warned of serious rot affecting the steel members that run through the sills. They aren’t easy to inspect even after removing interior trim, so tread carefully if you’ve any doubts about condition. It’s also worth checking the condition of the front longerons/underframe that bolts onto the front of the chassis; it can be damaged by impacts or incorrect jacking.

Some exterior bits are still available new and with a number of cars having been scrapped there’s a decent supply of used parts, too. Watch for damaged rear lights units, though, as replacements are around £500 each. The final check is the hood which was never known for being watertight, although things improved for the Series 2. Replacements are available if the cover is badly split or abraded, and although original ones are pricey there are more affordable alternatives.

Engine and transmission

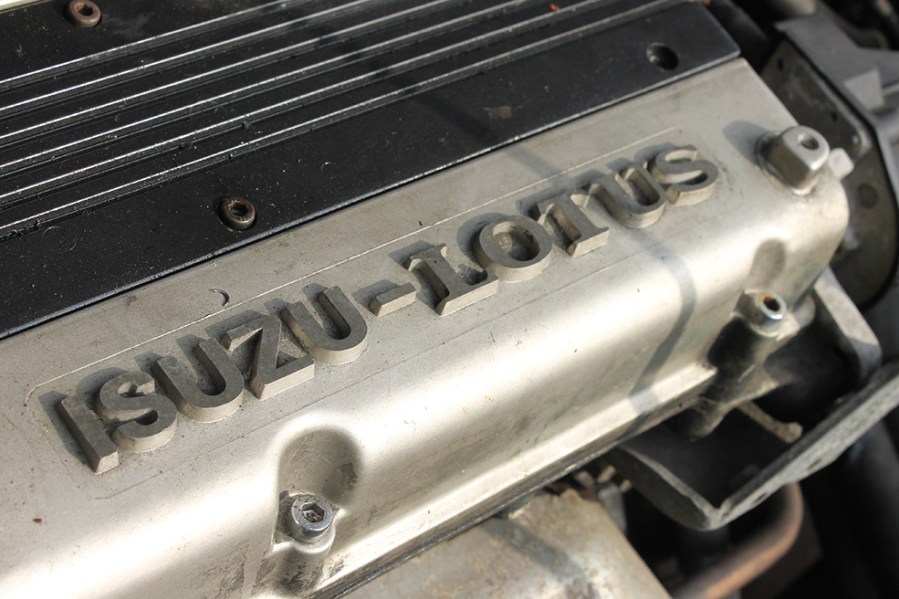

The Isuzu-sourced 4XE-1 engine made 130bhp or 165bhp in SE-badged turbocharged form (detuned to 155bhp in the Series 2 thanks to a catalytic convertor), the latter proving enjoyably punchy with 0-60mph despatched in 6.5 seconds. With careful maintenance the unit is considered pretty much bulletproof and can easily cover in excess of 200,000 miles, so look for a record of oil and filter changes every 5000 miles.

Oil changes will also help protect the IHI turbo, which has proven to be very reliable. Equally important is renewing the cam belt every five years or 50,000 miles – budget around £650 at specialist if you replace auxiliary belts at the same time. Oil leaks can be a bugbear and it’s wise to spend time checking the health of the cooling system as overheating can lead to head gasket failure, and fixing that is a time-consuming job. We’ve also been told that cracks can occur in the cylinder head and that turbo wastegates can seize although neither are all that common.

Fuel injection and engine management systems aren’t known to be troublesome, either, but look out for warning lights and uneven running just in case. And while we’re on the subject a remap can take the engine to around 200bhp without any deleterious effects. Ensure that such a boost hasn’t taken its toll on an already tired clutch, though.

That leads us on to the transmission. The five-speed manual gearbox in the M100 is usually trouble-free unless abused. Problems usually relate to the shift cables which can break at their ends; replacements are a few hundred pounds but they are fiddly to fit, which bumps up the labour bill. They might just need adjustment by someone who knows what they’re doing.

Suspension, steering and brakes

The suspension in the M100 comprised unequal length wishbones and coaxial springs/dampers at both ends, and with careful attention to the geometry it resulted in a fine-handling car. Unless the example you’re considering is at the project end of the spectrum it should all be in good shape; check for weeping dampers and bushes and ball joints nearing the end of their life. Everything is available for an overhaul, although costs will soon mount up. S1’s could suffer from corrosion in the rear lower wishbones – they were galvanised for the S2 – and the front items are also prone to rot, but it’s likely previous owners would have tackled this by now. In any case, improved items are available but they aren’t cheap so replacing them at either end will result in a four-figure bill.

Brakes were ventilated discs at the front and solid items at the rear and are more than up to the job. Look for corrosion on little-used examples, and while upgrades are available there’s not much need to take this route unless you’ve notably increased the power output. Standard discs and pads are easy to source and aren’t expensive.

As for the steering, the S2 got power-assistance as standard and it’s the better option; make sure you’d be happy with a manual system before you commit. The assisted set-up needs a check for any leaks from the hydraulics, and bear in mind that replacing the rack is fairly time-consuming. A new one can cost in excess of £1000 but you can source reconditioned items for a more reasonable £300-400. The original 15-inch alloys fitted to S1s could prove a bit soft so don’t be surprised to find aftermarket wheels fitted instead. The S2 got 16-inchers.

Interior and trim

We’ve already mentioned that the hood struggled to keep water out, so the first check is for signs of damp in the cabin. Examine the condition of the window seals, with a particular focus on the header seal at the top of the windscreen – a replacement kit is around £350 but it can be a pain to fit. Some of the other seals are becoming tricky to source, too, so don’t assume this will be a quick and easy fix. Expect a few rattles from the interior, although the Elan fared reasonably well in this respect, and the leather trim generally wears well, too. The driver’s seat can get a bit saggy but it’s not an especially difficult job to tackle.

Assuming the cabin is in good shape it’s a good idea to spend a bit of time ensuring that electrical items all work as they should. It was all reasonably reliable, but checks should focus on items such as the electric windows – a new regulator assembly is around £260 – and the central locking. And make sure the pop-up headlamps do just that as motors can fail, although reconditioned ones can be sourced for less than £100. The standard fit alarm and immobiliser can go on the blink, too (check the operation of any aftermarket items) and one specialist told us that hazard light switches are hard to find.

Air-conditioning was a rarely specified option but if it’s fitted check it’s working. On the whole, the cabin of an Elan was a comfortable and well-equipped place to be with decent levels of build quality. Trim and equipment changes between the two versions were generally of the detail variety, so it shouldn’t have any impact on which you might choose.

Lotus Elan M100: our verdict

We’ve all heard the clichés about Lotus’s being troublesome, but that’s not something to worry about if you’re tempted by an Elan M100. And tempted you should be. Not only does it perform and handle superbly – ignore any guff about it being front-wheel drive – but it also makes for a very practical proposition given its two-seater sports car credentials. The cabin is comfortable and usefully roomy, and with a decent boot it makes for a car that can handle long-distance touring with impressive aplomb. It’s abilities on more challenging roads will certainly put a smile on your face, too. And you can enjoy all of this safe in the knowledge that there’s excellent club and specialist back-up on hand.

Combine an element of rarity with a fantastic driving experience and it’s no surprise that values are buoyant, though nowhere near as high as they probably deserve to be. Ignoring projects and timeworn cars that hover around the £2000 mark, nice examples span the £6000–9000 bracket, and even the very best can be found for £14,000–16,000. There’s usually a reasonable number for sale, too. Normally-aspirated cars are worth less, but they are few in number and you’ll almost certainly want the turbo anyway. It’s reasonable to expect that the increasing demand and prices for the Elise will see attention turned to the Elan, so now’s the time to buy.

Lotus Elan M100 timeline

1989

The M100 Elan is launched in Series 1 form. Initial sales were strong, but just 3855 would be made before the plug was pulled in 1992.

1994

With Lotus under new ownership and a stock of spare engines to use up, production is restarted. The Series 2 is only sold in the UK.

1995

Production ends for good with 800 Series 2’s built. Tooling is sold to Kia who make another 1000 or so between 1996 and 1999, although they aren’t sold in the UK.