The badge-engineered Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud and Bentley S1 straddled the divide between pre-war coachbuilt cars and the modern Silver Shadow. Here’s how to buy one

Words: Iain Ayre

Around 13,000 Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud and S-series Bentley models were built between 1955 and 1965. The car utilises an old-school separate chassis and features relatively old-fashioned styling; Designer David Blatchley was asked for a traditional-yet-modern design, an entirely contradictory brief.

His early designs were rejected but a quick sketch more or less drawn in a corridor outside a board meeting got the thumbs-up. This was possibly an emotional rather than logical decision: if you look functionally at the body, the back doors are too short for a limousine.

The body shape is actually that of a huge sports car, which is why it’s such a beauty – and why it looks even better as a two-door. The 1955 Silver Cloud was the first car to have both its body and its chassis manufactured by Rolls-Royce, although there were still a good few coachbuilt cars assembled on the same chassis.

The Silver Cloud and Bentley S1 are the same car save for badging and radiator grille treatments, as are all Rolls-Royce and Bentley models from 1946 onwards (ignoring recent BMW and VW models).

The first Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud series, running from 1955 to 1959, used the 4.9-litre straight six in its ultimate, perfected form. The Cloud II and Bentley S2 from 1959-1962 featured power windows and steering, and early versions of the alloy V8 that would power Rolls-Royce and later Bentley models until replaced by VW engines in 2020. The Cloud III and Bentley S3 from 1962 to 1965 used better-developed versions of the V8 engine, and featured quad headlights and a lower bonnet line.

Bodywork

Body rust points to be wary of are the front body mounts, the complex sill/inner sill structure, the rear inner and outer wings, the front wing bottoms and the sidelight pods. Check out the range of body repair panels sold by parts supplier Flying Spares, because that very usefully tells you exactly what rusts! The doors, boot and bonnet are made of aluminium, which helps with body restoration bills.

The chassis is fairly substantial and generally lasts well, although the battery is mounted on top of the rear chassis leg on the right, frequently with unpleasant consequences. The body mounting outriggers are also vulnerable. They are complex fabricated pieces, easier to buy than to recreate. Historic oil leaks mean the front of the chassis lasts better than the back.

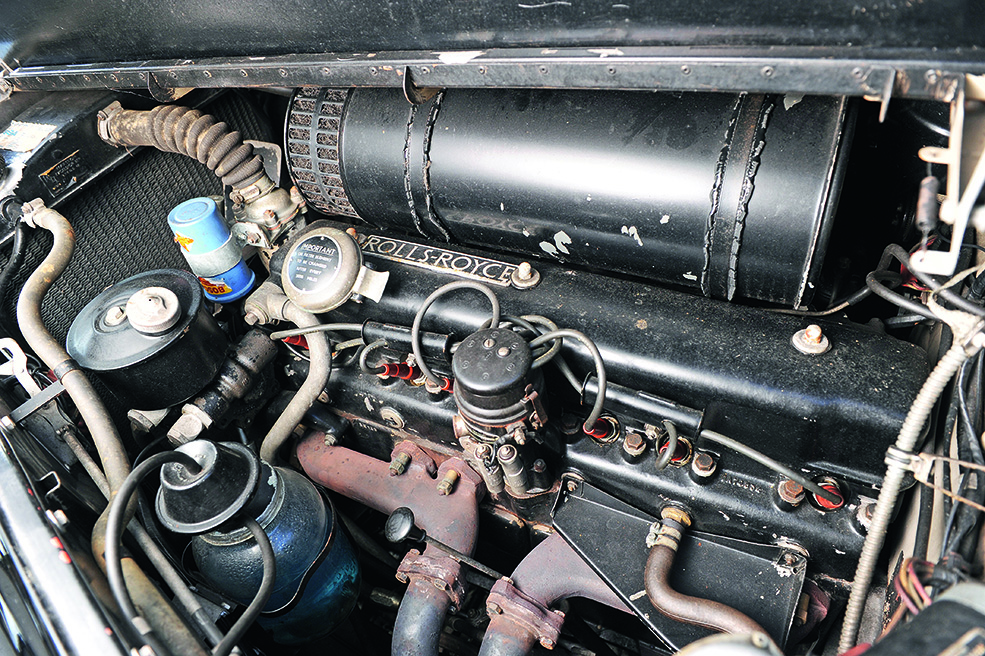

Engine and transmission

The straight-six fitted to the Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud I and Bentley S1 is the final 4877cc version of the post-war engine, with plain bores rather than the unfortunate chrome part-bore inserts that doomed many 1940s and 1950s MkVI engines. If looked after, the Rolls-Royce straight-six is extremely reliable and reasonably economical. Its performance is based on torque rather than horsepower, and while the power is no more than adequate for moving a 4650lb car, it is relaxed and very smooth – at idle you might have to check the oil pressure gauge to see if the engine is running.

The Silver Cloud II’s 6230cc V8 offered more power at the cost of poorer fuel economy, and 113mph rather than 103mph, but early versions of the V8 suffered from cam problems, piston scuffing, liner leaks and premature wear.

By 1962 the design was sorted out, and it stayed sorted for the next 58 years. Waterways can clag up over the decades, leading to overheating and head gasket issues. If you’re not a purist you can backdate a 6.7-litre V8 from a Shadow, and if you’re a hooligan you can backdate a cheekier version from a Bentley Turbo R. The 1959-on retro-fitted V8 barely fits in the car: the rear right spark plugs are changed via a detachable inner-wing sub-panel, with the wheel removed.

The automatic transmission is basically a General Motors Hydramatic four-speed automatic in a Rolls-Royce version with a mechanical brake servo clutch assembly on the side. Don’t buy a car with the early semi-automatic, as the available internal rebuild parts don’t fit and the rebuild invoice will be monstrous.

The fully automatic Hydramatic box is tough enough to be a favourite with drag racers but doesn’t like being ignored, so barn finds may require a rebuild. The transmission is unconventional, with a fluid coupling rather than a torque convertor. It also has adjustable bands: thumping into 3rd gear often indicates maladjustment (usefully, adjustment is external) rather than a serious problem.

Suspension, steering and brakes

This is straightforward, with a live axle on cart springs at the back and a very good independent coil system at the front, copied from a 1930s Packard. The shocks are lever-arm, adjustable at the back between a smoother ride or sharper handling. The one-shot pre-war Bijur pedal-operated chassis lubrication system is partly replaced by additional greasing points at the front. If looked after, the components last very well; if not, repair costs are substantial.

Optional power steering is genuinely optional: many owners don’t bother upgrading it. The later Silver Cloud models have possibly too much power assist on the steering, like the Silver Shadow. It initially feels weirdly disconnected and lifeless, although you quickly get used to it and may grow to like it – it’s part of the remoteness from your surroundings that the Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud offers. Like the MkVI and the later Silver Shadow, handling on the Silver Cloud is not bad at all: it gives a good account of itself when thrown around, although it’s hard work and not really the point.

The braking system is a complex semi-hydraulic, semi-mechanical system with useful redundancy: even a total hydraulic failure leaves the back brakes fully functional. There is a mechanical servo on the gearbox, and adjustment is complicated but achievable.

If you enjoy fiddling and fettling, these cars offer plenty of that. In comparison with their original cost, which was about the same as a semi-detached house, mechanics’ time was worth nothing, so no effort was made to make any maintenance or repair tasks easy or quick. The brakes are powerful, and do not need updating to discs.

Interior, trim and electrics

The interior is walnut veneer and Connolly leather, but it’s not much different to any other high-quality car when it comes to restoration. Seat-back picnic tables aside, the acreage of expensive materials is not much more extensive than a Rover or a Riley, as most of the car is bonnet and the cabin is not particularly big.

One thing to watch is the tendency shared with Porsche for everything appertaining to Rolls-Royce to cost a lot more. A seat is a seat is a seat: point that out until you get the right price.

The electrics are both good and bad. The wiring is of heavy gauge and the electrical system is very well made. It’s also very extensive and complicated, with over-the-top flourishes: one of the controls should be a simple rheostat, but instead it comprises a dozen separate contacts set in a ring, hence twelve wires in the sub-dash spaghetti rather than one.

The chain-operated electric windows can be tricky, and need maintenance: it wouldn’t be a bad idea to mix and match back and front mechanisms to locate the least-worn bits inside the driver’s door. The heating and air conditioning system is complex and vulnerable to corrosion, cracked old hoses and incontinent matrices. It’s huge, and like the V8 has been stuffed into the car as an afterthought, wherever it would fit. One fan is mounted inside a sill!

If the radio works, it will likely be AM-only. Many plaintive posts on the Rolls-Royce forums concern attempts to fit aftermarket electronic ignition. Don’t do that: the twin ignition points system, once set up, works perfectly and retains three working cylinders if a contact point fails.

Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud: our verdict

While its the more modern Silver Shadow that has captured the imagination of enthusiasts in recent years, there’s still plenty to be said for the older, arguably more regal Silver Cloud. It remains a great expression of ultimate luxury, is packed with solid engineering and could even be a DIY project if you have the requisite funds and skills.

The good thing about most older Rolls-Royces is the abundance of specialist support; there’s no need to get your hands dirty if you don’t want to and you can be confident that your investment can be well cared for.