Who doesn’t want a classic six-cylinder GT car in their life? We’ve chosen some of the best

Words: Sam Skelton

Fiat 130 Coupe

We don’t expect Fiats to be this size – the 130 Coupe is very nearly the size of the Jaguar XJ6 Series 1. And nor do we expect them to be quite so sharp suited; the rectilinear 130 Coupe is a work of art, oozing cravat-wearing 1970s cool from every single panel gap from its oblong headlamps to its sharply angled tail. There’s no attempt here to impart soft, feminine curves to the flanks, no attempt to weave sexuality into metal. The 130 Coupe is sharp, purposeful, and seemingly effortless in form. That makes it, arguably, the coolest looking car in this group by far.

It’s not the quickest car here either, its engine tuned for torque rather than power. But to want to drive this car fast is to miss the point. As a grand tourer, it offers a six-cylinder soundtrack at a comfortable pace, but prioritising a sort of soothing ease above any of that common, vulgar exertion which comes with pushing a car hard up a mountain pass.

Inside, crushed velour in deliciously 1970s colours dominates, though the huge drilled spoke steering wheel and the abundance of orange wood do their best to live up to that ultimate 1970s promise. The automatic transmission selector is a work of art, and the whole cabin oozes a louche, informal opulence. You want one. Of course you do. And if you get a good one, the market suggests that a Fiat 130 Coupe could be as attractive as an investment as it is as a car.

BMW 6 Series

The mighty BMW CSL and ‘Batmobile’ might have dominated the sporting market of the early 1970s, but its successor was a grand tour-de-force. The 6 Series was based upon the architecture of the new 5 Series saloon, topped off with a body which owed more to the theory of evolution than it did to contemporary thinking.

The 633, the first 6 Series, looked for all the world like an updated CSL – not that this was a bad thing. It also handled and went well, but the launch of the 635CSi in 1978 shifted the 6 Series into true bahnstormer territory.

The best thing about owning a 6 Series is the hardiness; many people still use them as everyday cars to this day and if you can afford an average of low 20s fuel economy, the car will thank you for it.

Corrosion, as with anything from the 1970s, can be a concern. But if the lower bodywork is OK, there’s no rot in the pillars and you keep your 6er undersealed and rustproofed, it’ll just keep on going until you stop. 60 in under 9 seconds, space for four, a big boot and rear-wheel drive fun has always been a tempting mix, and while you’ll be paying around £15,000 for a nice 635 these days, it’s not all that long since they were five grand. The upward trend shows no signs of stopping – this could be the cleverest investment here.

Reliant Scimitar GTE

Mechanically, the Reliant Scimitar should be little different to the Capri listed elsewhere here, given that it too uses a choice of Essex and Cologne V6s in 3.0 and 2.8 form respectively. Where the Scimitar differs strongly from the Ford though is in its image. The Reliant, helped by its royal associations – come on, we had to go there – was always seen as a more upmarket proposition, more of a rival to cars like the Triumph Stag and the Peugeot 504 coupe than the everyman hero from Dagenham.

This was backed up by its trim – the Reliant was always plushed, especially in post 1975 SE6 form when Reliant decided truly to target the big boys in the directors’ car park. Most are automatics, but while this will disappoint the more sporting driver it’s a good match and suits the Scimitar’s grand touring leanings.

You might not think it for a GRP car but again rust is the killer – this time in the chassis, which wasn’t galvanised until the launch of the Cologne-engined SE6B models. It’s difficult to check, so receipts for chassis replacements or repairs will stand any Scimitar in good stead if recent. Again, nylon trim can be an issue, though vinyl trim is better-wearing. You’ll find myriad parts bindetails inside and out – all easy to get. But beware the Dunlop composite wheels on late SE5 and early SE6 models – they have a steel rim and alloy centre, riveted together. Galvanic corrosion can kill these wheels, while the chrome plate on the steel rim can be expensive to repair as rechroming involves separating the wheels.

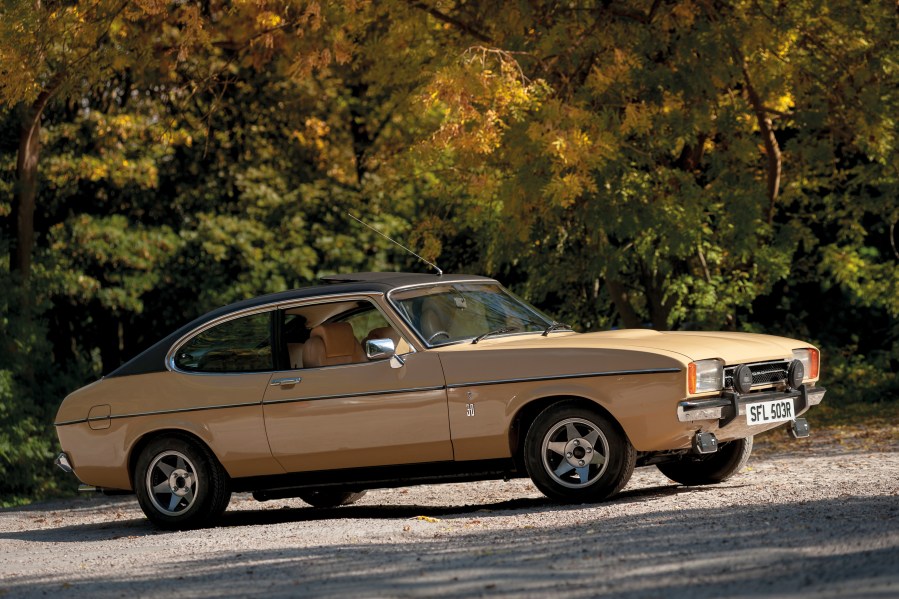

Ford Capri

The Ford Capri is the obvious first choice for any round up of 1970s V6 GTs – it’s the car you always promised yourself, after all. The Capri’s popularity new and now means that it’s one of the best-supported family friendly classics on the market, and with almost everything available and values continuing to rise the Capri seems like an obvious choice for so many. Whether new to classics or looking for a new classic, the Capri should be on your list.

All 1970s Capri V6s came with the Essex V6, which is well-supported on the spares market. Later cars, if the decade doesn’t bother you, were fitted with the Cologne V6 from the Mk2 Granada – this is again a well-serviced unit, so mechanically a Capri should pose no problems.

Corrosion is the primary thing to check for when buying a Capri; as with all 1970s Fords they like to rot. This decade spans all three series of Capri production from Mk1 to Mk3, each of which has its own rot spots – but a general indication can be had by checking sills, valances, the boot floor and the floorpan. Door bottoms can also rot out, as can sunroofs when fitted and windscreen frames. Make sure you find a car with good trim, as much model specific trim can be difficult to source today – poorly paint can be revived but stretched nylon can’t be put right without a lot of time spent browsing samples.

Vauxhall Royale

Sadly, it’s not quite Pulp Fiction. This Royale came with chintz. With its automatic gearbox, carburetted 2.8 litre six, crushed velour and fake wood, the Vauxhall Royale spoke of the aspiring middle classes better than any Volvo estate could have done. And with the Royale coupe, that sense of success was melded with raffishness not found in the saloon – here was a car which brought the grand tourer right into the heart of suburbia.

The Royale range was Vauxhall’s take on the car mainland Europe had as the Opel Senator – and indeed, even in Britain the Opel Senator and its Monza coupe variant were advertised to the sort of people who felt that a prestigious German brand brought respect from the neighbours. But the Vauxhall was better value when both models were new – barring the dashboard the Opel badge bought you nothing but a fuel-injected engine.

Sadly, so few Royale coupes exist that we can’t advise you search for one unless you’re truly committed. Not when the following decade brought a performance evolution of its sister car which still has ardent admirers among the Autobahnstormer community today. The Opel Monza GSE is a big-engined, German-badged Royale with a more contemporary interior, and makes for an excellent classic grand tourer. You lose the oh so ’70s trimmings, but what you gain in terms of power and relative ease of parts availability more than makes up for it.

Datsun 240Z

If the rest of this list seems too sedate, too laid-back for you, then we’ve a treat in store. Datsun’s 240Z might not be the first 1970s six-cylinder sports GT you think of, but it’s one of the best; showing the Triumph TR6 how it should be done. It’s pretty, with its cubist E-type looks hiding a cockpit which is more than capable of handling six-footers, and that 2.4-litre straight six under the bonnet is good for 0-60 in eight seconds dead.

It’s no blunt instrument, either, because the 240Z rides and handles as well as it looks and goes. The steering is responsive, the brakes sharp for their era, and the gearchange perfect. If anyone ever asks what made the Americans jump ship from the British sports car industry, we only have this car and the Mazda MX-5 to blame.

Buying a 240Z can be fraught with danger for those who don’t know the model’s main Achilles’ heel – but then, you’d already guessed that this is rust. Check everywhere – all the forward facing panels including the bonnet and headlamp cowls are prone to stone chip damage, while door bottoms and sills can trap water. Check the rear slam panel for corrosion as a result of chipping paint when the tailgate is lowered, inner wings, suspension turrets, floorpans and chassis rails. If all this is good, check the arches. Mechanically you’ll have few issues with a 240Z and parts aren’t too hard to source if you’re in the Z community, so if you find a solid example you should be set.

Porsche 911

The Porsche 911 has been a hero car for over half a century. Launched in 1963, by the 1970s it had matured from a sports car into a competent tourer, with a longer wheelbase offering greater stability and more power courtesy of an enlarged derivative of its flat six engine. The Turbo added unpredictability and earned itself a reputation as a car which played tricks, though the standard 911 still appealed not only to ardent drivers, but to boys who put pictures on bedroom walls.

Those boys are now men, and the 911 is an appreciating classic. Back in the 2000s, a 1970s 911 could be had for under £10,000, but now the market is more buoyant than ever and the £28,000 a Targa will cost you now is the cheapest you’ll find a usable 911 of this era. Early ’70s examples are now nudging £70,000 in good condition.

Despite the galvanised body from 1975, rust is still the biggest issue on any old 911, not only from stone chips to the nose but also from trapped mud underneath. Check the sills and ‘kidney bowls’ running ahead of the rear arches first, while pillars can be an issue if your 911 has a sunroof fitted.

The boot floor, floorpans and torsion tube are also known rot spots. UK cars have often been restored already and you can’t always guarantee the quality of the job, so many investors are now choosing to buy and restore dry state American cars instead.