When luxury cars were put up against a wall of change, the BMW 5 Series and Mercedes W123 made history. We put them head to head

Words: Aaron McKay Photography: Gregory Evans

The times in which cars are developed always tend to shape them one way or another. For these two, their context remains relevant today. As new cars, they offered clever engineering solutions to the problem of reconciling the executive car with the increasing cost of fuel, and as classics they offer a somewhat conscientious, or perhaps simply just apologetic nod to the environmental pressures of today. But simply as pieces of history, they are each a fascinating insight into the state and direction of Mercedes and BMW.

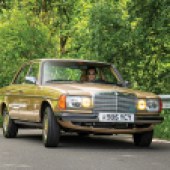

The family resemblance that the W123 has as a Mercedes-Benz is immediate and striking. While the reality is that designers deliberated over every detail during its development, the result is a car that looks effortlessly natural, and one that has proved timeless. When I first saw Jack’s 1982 300D gliding along a little road in the Peak District, my immediate thought was: now that is a Mercedes-Benz, and I think that’s the same for many people. There were nearly 2.7 million examples of this generation built, and over 2.3 million of them were the classic saloon bodied cars. Much like its predecessor, it was a global car and, for many markets, this relatively high-volume Mercedes would become a lasting icon of the marque.

It’s in the design that the W123 really does stand out, then and now. The W116 S-Class may well have inspired its lines, but the smaller W123 appears better proportioned and does the styling more justice. It’s not just distinctive as a whole either, it’s thoroughly clever when you stop to consider the details. The big, wraparound front indicators remove the need for side-repeaters, the taillight design prevents dirt build-up, and the headlights neatly integrate a lower trim piece for the wipers to sit without obstructing the forward beam. The chrome running strip around the edges of the car protects the paintwork from small dings as expected, but also manages to look good rather than just a piece of necessity.

Aerodynamics played a significant role in the external design, too, but Mercedes still managed to keep its vast grille; now lower and wider, met either side by the headlights. It’s also a superb example of the subtlety of Mercedes stylists: it appears at first glance to be lifted from the S-Class, but in fact features a less intricate lattice that visibly reduces its depth, and it tapers inwards at the bottom instead of remaining square. It’s smaller without being small, and that philosophy runs through the car.

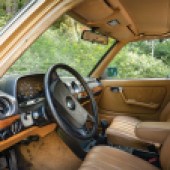

Inside, it’s arguably even more pleasant. Soft touch plastics, high quality vinyl and carpets trim around a modern looking dashboard and centre console that all looks quite normal these days but the whole thing is quite remarkable for its modernity. Little touches are here too, from the neatly stowed inertia reel seatbelts, rear footwell air-vents, to the speedometer that has markings for mph and kph. Whether your seats were fabric, MB-Tex, or leather was a matter of cost and there were of course a variety of colours to choose from.

The 300D was a highly specified car, at the top of the diesel range, and especially so in the UK. Given its exceptionally high price here, it was decided that power steering, central locking, and automatic transmission would be standard equipment. You’ll notice that Jack’s car here is a manual car, a feature that comes with its being left-hand drive and, originally, from Spain. His does have, though, electric windows.

There was an extensive options list that can keep any prospective buyer today entertained or frustrated, playing a sort of Mercedes equipment bingo. Some cars were known to have a heated passenger seat only, just as one example. The option list shifted as time went on, with lower models gradually picking up the nice features either as standard or within cost reach, while later cars could be even be specified with an airbag and ABS. Also as time went by different colours inside and out became available, with the big changes coming in 1980 and 1983. Today, one has to be careful that they know their paint code when restoring a W123 because names can be used twice for different shades.

The five-cylinder diesel 300D was available right from the introduction of the W123 in 1976, and had already been seen in the previous generation W115 ‘/8’ car. Aside from being the most powerful in the range, it was also a leap forward in mechanical refinement. This was thanks not only to the extra cylinder count, but also a heavier flywheel and viscous-coupling radiator fan. Another clever detail is that the glow-plug priming function is built into the ignition barrel, so rather than an extra switch it is automatically part of the start-up procedure. It achieves something that remains relevant today: diesel performance with less compromise.

While its 87bhp and 127lb ft might seem like painfully low figures, the performance can be deceptively close to its petrol-fired siblings and indeed once on the move, its flexibility really starts to show. You also find the engine in a much sweeter state above idle speed, whirring along with silky smoothness only betrayed by the offbeat tune of its odd cylinder count. Performance sits perceptibly in reserve, obeying when called for but never really inviting you to up the revs.

Progress in this car is perhaps best observed using the oversized clock where a tachometer might be, but that’s not to say it’s frustrating. In fact, it’s bewitchingly charming and addictive for its feeling of being unstoppable. You can understand why so many enthusiasts aren’t as envious of the later 123bhp, 184lb ft turbodiesel than you might first expect.

The rest of the dynamic package follows this theme of capability, smoothness and security. The gearboxes are robust, the manual offering tall gearing for what Mercedes calls a 90mph ‘cruising’ top speed, while the automatic’s shift programme could well suit the 300D’s power delivery better than any other model in the range.

The ride and handling package is, as you’d expect, very good and tending towards the firm-riding high-speed stability of the German tradition. The W123 has a wider track than its predecessor, now with zero-offset and anti-dive geometry at the front, just like the S-Class. There’s also the expected worm and roller steering, mounted on a hydraulically damped column.

Clever use of the wind tunnel isn’t immediately obvious in the 0.42 drag coefficient, but catch yourself in a storm at high speed and the W123’s side-wind stability will impress a deep respect for the work done all those years ago. Just think that this is nearly 50 years old, and you can’t help but have proper respect for those who developed this car.

Next to the Mercedes, the BMW looks small, almost dainty. There’s a delicateness to its lines that carries little of the upstanding weight of the Mercedes, belying a kerb weight some 200kg less than its rival. The E28 also sits lower, its side skirts and lower bumpers as much of a design point as the W123’s huge grille and broad shoulders.

It is, of course, all classically BMW and indeed much of it is carried over from the previous generation BMW E12 which, ironically, was designed by ex-Benz designer Paul Bracq. Keeping the same sharp-edged nose and Hoftmeister kink as the E12 and its predecessors, the E28’s changes were mostly under the skin.

Beyond a slightly shorter wheelbase and some subtle tweaks made thanks to a newly acquired in-house wind-tunnel, there was little to visually point to dramatic change. Except there was big change, and it would point forward the direction for BMW for decades to come. The E28 was one of the first BMWs to chase out weight, employ electronic engineering solutions, and, at the same time, offer the driver an up-to-the-minute cabin.

The E28 managed to ditch a whole 100kg from its predecessor the E12. This was achieved through the use of thinner glass and steel in strategic locations, less use of sound deadening. This was afforded by clever thinking and designing out faults elsewhere, like reducing NVH with new engine mounts.

It also helped that the E28 benefited from the development of the first-generation E23 7 Series, and not only did this help with ride and noise suppression but it also went some way to calming the infamously spiky handling characteristics of BMW’s long-used semi-trailing arm rear setup.

New geometry, links, and much of the 7 Series front end made a massive difference. Handling was more progressive, while retaining high-speed stability and steering sharpness. It would prove to be a philosophy of design for many BMWs’ suspension setups well into the future.

Inside, the dashboard was angled more aggressively towards the driver and we all know how much of a BMW trademark that is today. While not quite enjoying the same level of beautifully crafted attention to detail of the Mercedes, there is a sense of quality about the E28’s cabin and it does have one trump card: toys. The M5 may well have been the most impressively equipped, with things like electrically adjustable headrests, but even lowly 520i models gave drivers a 10-function trip computer.

There’s more: the Service Indicator system judged when the car was due a service based on driving style, displaying progress on a green, amber, to red scale, and also lighting up a dash full of component icons on start up. Not only does it all feel very modern, but it gives the driver a sense of control, something that was right on the money for the customer of the day and quite possibly a key attraction for anyone looking for a fun to drive classic today.

If you’ve noticed that this BMW has a tachometer, instead of a giant Mercedes clock, you may well have also noticed that it tops out at 5000rpm. A diesel, surely? A twist of the key immediately kills that idea, as the light starter brings about the unmistakeable hum of a BMW straight-six petrol. It pulls cleanly, effortlessly, up the revs and then the automatic box slots in a gear early.

At first you think that it’s missing the best bit, but there’s more to this engine than you realise at first. You see, BMW was far more progressive and adventurous in using electronic control in their engines than Mercedes, and in doing so they began to discover ways to optimise the petrol engine for economy.

The 1979 BMW 732i had featured computer-controlled air, fuel, and ignition systems, and in 1983 the E28 525e stepped this up with a specialised high-compression 11:1, 2.7-litre engine, mated to a tall-geared, early shifting automatic gearbox. BMW had found that keeping an engine around the 2000rpm mark not only reduced direct fuel consumption but also kept vacuum losses and engine running pump drains to a minimum.

The whole drivetrain was set up to offer high levels of torque and, with the help of Bosch Motronic engine management, encourage more efficient driving. Figures are 125bhp, 177lb ft, and 28mpg (average). The driver really only notices that the tachometer needle resists the right hand side more than you’d expect. Like today’s ECO PRO driving programme, there is much more clever stuff going on behind the scenes than you realise.

BMW 5 Series vs Mercedes W123: our verdict

Based purely on fuel economy, it’s the BMW that wins. Its combination of low weight, computer-controlled combustion and tall gearing is too much for the surprisingly thirsty Mercedes diesel to match, even in manual guise.

However, the reality is that neither is going to deter you from going on a long classic road trip. Unless, of course, that road trip includes a visit to Paris, or another of the diesel-resistant cities of Europe that are increasing in number these days.

Besides, the real challenge between these two is in their charming characters. The BMW is impressively modern but has a wonderful purity about it that, upon seeing it, you immediately realise has been lost in a mass of bulk in the 40 years since its introduction. Its driving experience reflects that, and with the 525e’s powertrain there is a unique blend of smoothness and direct feel. The seats are soft, but the steering is sharp.

The Mercedes has a stronger sense of purpose, even if it does actually fall down when it comes to the miles per gallon. There is a feeling that it really will drive on forever, that the doors will never fall off, and nothing short of wind erosion will actually spell its final demise. That, and the wonderful character of the five-cylinder diesel engine is enough to endear it to anyone who hasn’t yet fallen for its timeless, just-right shape.

And yet it has to be the BMW that earns top spot here. The 525e has lived to see the petrol side finally push back against diesel, but it’s also that the E28 brings a philosophy of light weight, electronic monitoring, not to mention ergonomics, that makes it a more significant relic of automotive history. Even if I, personally, would have the Mercedes.