The ex-GM engine that debuted in Rover’s P5B went on to enjoy an extraordinary career. Here’s a look back at the development of the iconic Rover V8

Words: Andrew Everett

The Rover V8 engine had been a failure for its original American maker, but once adopted by Rover, British Leyland and a cast of many others, the engine became a resounding success, powering a significant chunk of the British car industry with character, sturdiness and a great exhaust note.

The history of this classic powerplant dates back further than you might expect. Work on the new ‘small’ V8 began at General Motors as far back as 1950, the earliest 3.8-litre unit being initially cast in iron but very quickly changed to alloy, along with a capacity hike to 4.1 litres. The idea was to build a smaller, lighter and more economical V8 to take the place of the dismal straight-sixes that powered many American compacts; there was no great hurry to do so, however, and it wasn’t until 1957 that Buick decided to really crack on and develop the unit with production in mind.

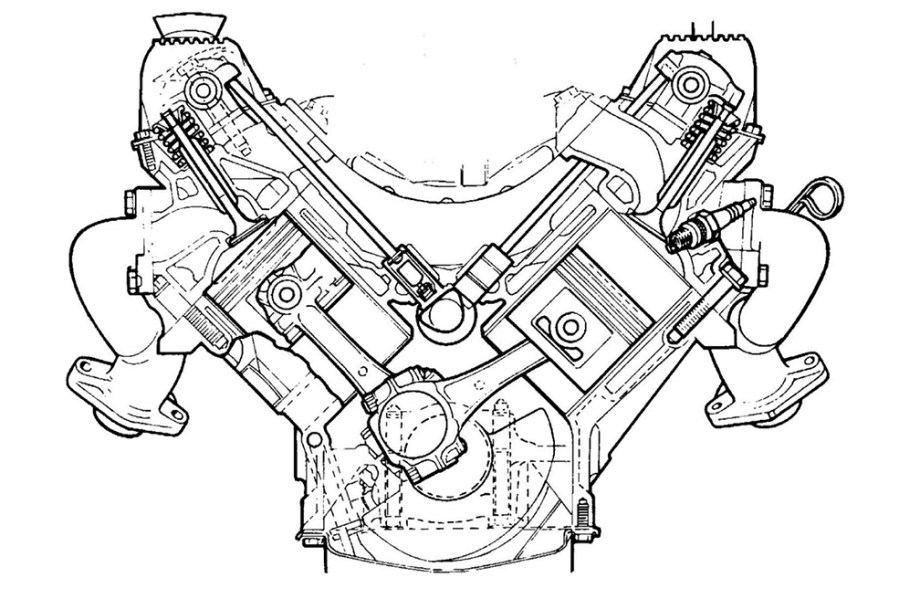

Early prototype engines fitted to development hacks used pure alloy blocks without liners; GM had worked out how to cast blocks with a high silicon content (the first of the ‘Nikasil’ type alloys that would later feature in the Chevrolet Nova, as well as various BMW and Jaguar V8s). However, while a hot engine would run forever, it was found that cold starts were causing serious bore wear issues not helped by the super-rich cold start fuelling that big carburettors gave. So, GM dropped that idea and fitted thin cast iron cylinder liners. These were not pressed in, but were cleverly held in place as the alloy block was cast around it. It’s easy to forget how inventive GM has been in the past.

Despite the troubles and cost of getting it into production, the 215cu in V8 began to be built from late 1960, destined to power the new Buick Special that was to make its debut in early ’61. This new small Buick was based on the latest General Motors Y Car platform that also sired the Buick Skylark (a more powerful upmarket version of the Special), the Oldsmobile Cutlass and F-85, the Oldsmobile Jetfire, and the Pontiac Tempest and LeMans models. In true GM fashion, Oldsmobile, Pontiac and Buick divisions were all very independent and had their own versions of the V8 with different cams, heads, carbs and compression ratios. In 1962, GM even produced a V6 iron-block version of the Buick V8 to power the cheaper versions, and the Oldsmobile Jetfire was (along with the Chevrolet Corvair Monza Spyder) the first turbocharged passenger car to make production, with an impressive 215bhp and 300lb.ft of torque.

By 1964, however, GM had abandoned the all-alloy V8. Stung partly by the Corvair nightmare (largely brought about via Ralph Nader’s controversial book, ‘Unsafe at Any Speed’), the company retreated back to simple, cheap-to-make thin-wall cast-iron V8s and left it at that for decades. A shame, but the US public wasn’t interested in small-engined domestic cars yet. Fuel was cheap and if you wanted a small car, a Volkswagen was what you bought. GM had made almost 750,000 ‘Buick 300’ 5.0-litre versions of the ‘small’ V8 with a cast iron block, but you’ll struggle to find one now.

Pre-British Leyland, Rover’s managing director was one William ‘Bill’ Martin-Hurst, who discovered the Buick motor on a trip to the USA. Bill had, the year before, been driven in a Buick Skylark and was suitably impressed. US cars may not have handled so well but they were solid, quiet and had tremendously smooth and powerful drivetrains. His famous meeting with the V8 was not, as is often claimed, at GM but at a company in Wisconsin called Mercury Marine. He was there trying to push Rover’s efforts in gas turbines as suitable boat power. On the floor in the workshop was a Buick V8 that belonged to Mercury’s director; it turned out that he’d used it in a racing power boat.

Intrigued by this shiny alloy V8, and knowing how old and heavy the 3.0-litre straight-six Rover engine was, Martin-Hurst had it shipped to the UK. He was also introduced to Ed Rollart at General Motors, in order to begin discussions. Back in the UK, the V8 engine was unpacked but was cold-shouldered by Rover engineers, including Peter Wilks.

Ed Rollart could not himself grant Martin-Hurst the licence to build the V8, but by this time Rover’s competitions department had installed the engine into a prototype 2000 hack – and the end result was so impressive, Rover couldn’t back out now. To reinforce opinion in the right places, Martin-Hurst drove the V8-powered 2000 to a Rover board meeting and tricked Spen King into driving it back from London. As he expected, King was extremely enthusiastic.

Meanwhile, General Motors appeared to be doing very little about the potential deal, not imagining that a small British firm was really serious. Martin-Hurst needed to go all-out to show GM just how committed he was. In the end, GM agreed not only a deal to sell the design and all rights to the engine, but also allowed Buick’s chief engineer, Joe Turley, to come to England to set up the manufacturing facilities and get the V8 into production.

In the end, Turley re-engineered the V8 to become a more European, higher-revving unit. Many changes were made to the production process, including sand casting the block and shrinking liners in. This was done by chilling the liners, sliding them quickly into a heated block and, once everything had expanded and contracted into one unit, machining and sending for assembly.

Many other things were changed as well. SU carburettors were felt to be more suitable both for economy and also to prevent fuel surge. While Triumph was using AC Delco ignition parts, Rover was still firmly in the Lucas camp, which meant the Birmingham-based firm had to develop its first ever eight-cylinder distributor.

September 1967 saw the UK launch of the Rover 3.5 Litre, codenamed P5B (with the B standing for Buick). Coupled to a Borg Warner Model 35 automatic gearbox and giving a claimed 140bhp, the newly revitalised P5 was an instant hit. This was joined in 1968 by the 3.5-litre version of the Rover P6 2000, known as the Three Thousand Five, a manual version of which appeared in 1971 badged as the 3500S. Not that the engine in the V8-powered P6 was identical to the P5B’s, as fitting it into the smaller P6 bodyshell meant using different exhaust manifolds and a re-routed exhaust.

The arrival of the S saw a small hike in power, with a new exhaust system that featured both downpipes (now of bigger diameter) merging into one pipe further back. The S model also replaced the original SU carbs with the new HIF6 types, with the float chambers in the base of the carb body. Rover’s output claims were now more realistic, and the S engine developed 152bhp at 5000rpm and 203lb.ft of torque at 2750rpm.

The engine was also finding a home in other BL products, notably the 1970 Range Rover, for which the compression was dropped from 10.5:1 to 8.5:1 to allow use of two-star petrol. The front timing cover and water pump position were also altered to allow the use of a starting handle, while the SU carbs were replaced with a pair of Stromberg CD2 units.

Inspired by the success of Ken Costello’s bespoke conversions, the MGB GT V8 was the next British Leyland model to use the powerplant, although fitting it into that sportster proved both costly and difficult for Abingdon’s engineers. In the end, the inlet manifold was revised to move the carburettors back enough to avoid an MGC-style ‘hump’ in the bonnet. To keep power down, MG used the low-compression Range Rover unit but with the Rover P6’s twin SU HIF6 carbs to give 137bhp.

Not every car using Rover’s highly praised V8 was an in-house model, of course, as Morgan had also employed the 3.5-litre unit to create the new Plus Eight of 1968 – a model that was typically Morgan in style but with the kind of power and performance the marque had never offered before. It was, of course, a big hit for the Malvern firm, and the Plus Eight went on to be the longest-running car to use the V8, finally ceasing production in 2004 after a 36-year career, outdoing the 32 years that the Range Rover racked up with Rover V8 power between 1970 and 2002.

A big year for Rover was 1976, when the exciting new SD1 finally went on sale, featuring a revised version of the venerable V8 that had been part of the British Leyland line-up for almost nine years by then. Rover’s first objective was to raise the rev limit, and it did this by improving the ports, manifolding and re-valving the hydraulic tappets to prevent them from pumping up at high revs. New extractor-type exhaust manifolds were used along with stronger valve springs and Lucas electronic ignition. A higher-capacity oil pump was fitted, the piston rings were made slightly thinner, and the water pump impeller was revised to prevent cavitation at high speed.

The result wasn’t so much about higher power (it gave 155bhp at 5250 rpm) but a better spread of torque, with nearly 200lb.ft at just 2500rpm. This was an engine that could buzz up to 6000rpm to make it really fly, but also lug a heavy Rover along with a five-speed gearbox and tall gearing.

The next major change to the V8 came in late 1982 with the introduction of the SD1-based Rover Vitesse. Power was raised to 190bhp thanks to the use of Bosch Lucas L-Jetronic fuel injection. At this point, production of the V8 was moved from its traditional Acocks Green facility to Land Rover in Solihull.

The SD1 was usurped in 1986 by the new Rover 800, BL’s latest model to be co-developed with Honda, but the famous V8 engine was far from dead. Morgan was still using it, as was Blackpool-based TVR, which had offered its customers the Rover V8 since 1981 as an alternative to Ford’s V6. The biggest user of the V8 in ’86, however, was the Range Rover, with the original version still selling strongly thanks to a range of updates and extra versions, enabling it to remain in production until 1994. Just as the SD1 was being phased out, the Range Rover received its Lucas fuel injection system.

The V8 saw its first capacity increase in 1990 with the introduction of the 3.9-litre unit. This new 3946cc format was achieved by retaining the standard 71mm stroke but boring the block out to 94mm (up from 88.9mm). That in turn was joined by the 4.2-litre version in 1992, with the longer-stroke crank for this engine being developed for an ill-fated attempt at making a diesel version of the V8 in the late 1970s and early 80s.

Just two years later, a new generation of Range Rover was announced, codenamed P38A – a model that would eventually replace the long-running original, which was now badged as the Range Rover Classic. The 3.9-litre engine was revised and renamed the 4.0, although its capacity remained the same as before. Revised inlet and exhaust valves, extra block ribbing, bigger cross-bolted main bearing caps and lighter pistons were used, with the new engine producing 190bhp and 236lb ft of torque.

Although the 4.2 V8 wasn’t used in the P38A Range Rover, a new 4.6-litre version was. Launched in 1996, the new unit combined the 94mm bore with a new 82mm stroke to produce 4552cc, 225bhp and 280lb.ft. of torque. A change from the old-type injection system with the square top plenum chamber (called the GEMS system, a revision of the old L-Jetronic) to Bosch Motronic came in 1999, with an all-new and very modern looking alloy inlet with eight rounded pipes. Production of the 4.6 engine ended in 2002 with the launch of the new BMW V8-powered L322-generation Range Rover. The 4.0 finished in 2003, that final version of the engine giving 188bhp at 4750rpm, plus 250lb.ft of torque.

A 5.0-litre version of the V8 was built for TVR from 1992, achieved by combining the 90mm bore with a new steel crank with a 90mm stroke. Power from these engines was anything up to 340bhp with 350lb.ft of torque – more than twice the power of both the 1961 Buick original and the 1968 Rover version.

Production of the V8 finally ended in 2005, when the Land Rover Discovery was facelifted and re-engined. By this time, TVR had moved away from the Rover V8, and Morgan had discontinued the Plus Eight. With its alloy rocker covers and modern fuel injection system, the final version was a world away from the carburettor-equipped original, with its pressed steel rockers covers and pressed steel fan. And yet it was essentially the same engine. The ex-GM unit that Rover had adopted and developed over many decades had become the proverbial legend in its own lifetime.