The development of the Jaguar XK engine has been covered many times, but its history still has a few secrets that might surprise you

Words: Ian Seabrook Images: Chris Frosin, Jaguar Heritage Trust

Ideas for the XK engine famously began being formulated during fire watch sessions at the Foleshill factory in Coventry. William Lyons and his chief engineer Bill Heynes were the key instigators, but it was Walter ‘Wally’ Hassan and Claude Bailey, both of whom had been lured to Jaguar, who were really instrumental in making the XK leap from a fond dream to a production reality.

Once the war was over, thoughts could readily turn to the new engine, which Lyons initially wanted for a new range of saloons. Wary of competition, he realised there were greater profits to be had through the high-volume sale of saloon cars, so a sports car was not his main priority. But, with Heynes and Hassan both being huge fans of motorsport, it’s perhaps not very surprising that thoughts of a sports car began to brew in Coventry.

The initial thinking was to have four and six-cylinder versions of the new engine, and many four-cylinder versions were constructed. It is via Hassan that one such XJ4 engine became available for ‘Goldie’ Garner to use in his MG land speed record car in 1948, as it was constructed by Thomson and Taylor. It was powerful, pushing Gardner to 176.694 mph, setting a new record for a 2-litre engine. But, there were refinement issues; not much of a consideration when setting land speed records, but important for a road car of the type Lyons wanted to build. Ultimately, these issues could not be overcome.

What drove the need for a new engine? Simply Lyons’ desire to build a true 100mph sports saloon. That would require substantial power for the time, and it was quickly realised that the existing Standard-based six-cylinder engine then being used would not be able to provide it. With 160bhp considered the required figure, thinking turned to how best to achieve it. Hassan and Baily were initially sceptical of the overhead camshaft plan, perhaps because both had previous experience of such units and the difficulties such set-ups can create.

Heynes was more bullish, realising the advantages in terms of breathing and efficiency that an overhead camshaft layout would allow. He was no doubt backed up by Harry Weslake, a consultant engineer who had improved the cylinder head design of the Standard unit and now also lent his expertise to the XK project.

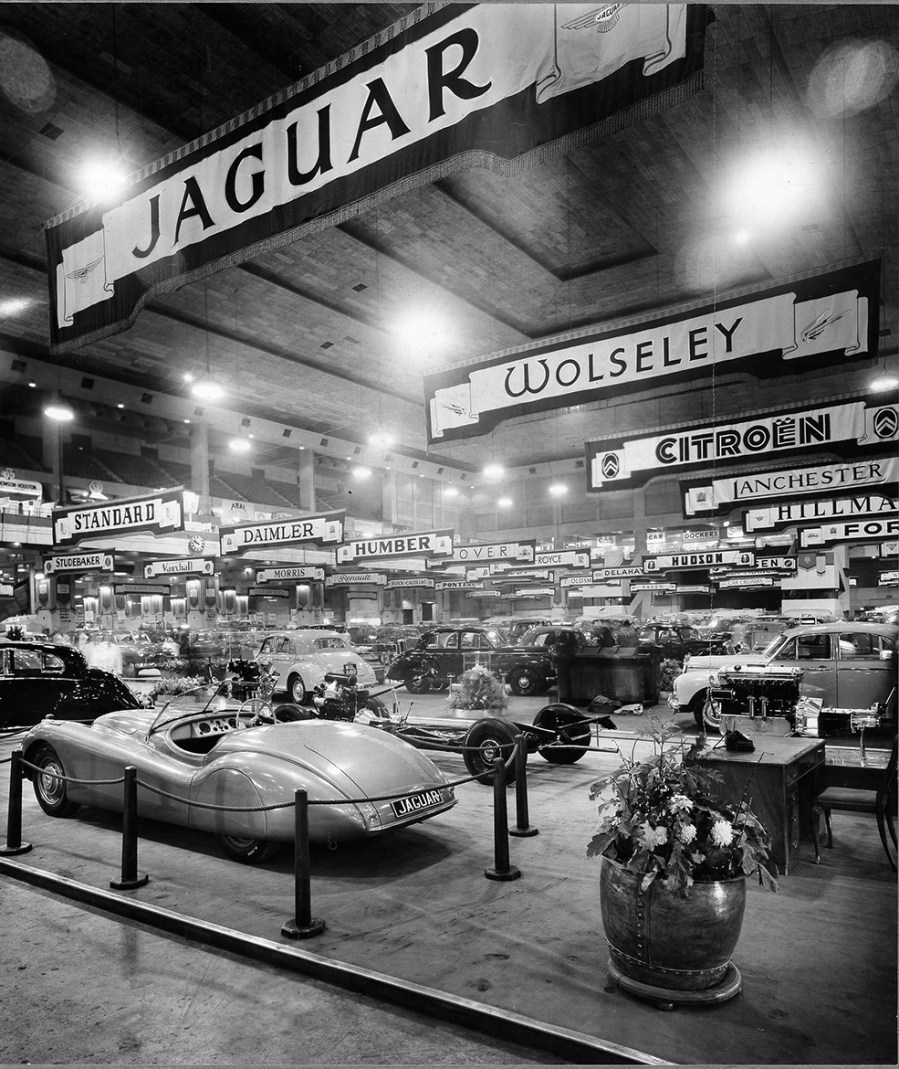

As the Earls Court Motor Show date of October 1948 was fixed, it became a real target. Lyons realised that his saloon plans were not sufficiently developed to reveal Jaguar’s next step, so the 3.5-Litre had been reworked into the MkV, with independent front suspension. But, Lyons wanted to create a greater buzz, and his engineers were only to happy to provide it. Maybe, what was needed was a sports car concept?

That this was a fairly late decision is revealed by the chassis structure of the XK120, a cut-down saloon chassis using torsion bar front suspension; Heynes was one of many British engineers influenced by the Citroën Traction Avant.

By September 1948, the final shape was getting close to the final design, but there was just one month until the Motor Show. Certainly, this first car, resplendent in bronze, was not a runner. There are rumours it may even had had a four-cylinder engine at the show, but the bonnet was not for lifting. Jaguar certainly did display four and six-cylinder versions of the new engine, with promotional material claiming that the sports car would appear in production as the XK100 and XK120 depending on power unit. But, vibration issues continued to plague the smaller engine, so four-cylinder engines were quietly shelved.

The Jaguar XK120 ‘Super Sports’ was seen by the motoring press on Friday 22nd October 1948, with one newspaper calling it superior to anything the Italians had in their arsenal. As well as the looks, there was further amazement at the price, for what was going to claim to be the fastest production car you could buy. Even before it turned a wheel, the XK120 was grabbing headlines around the world.

The potential was proven in Jabbeke, Belgium on 30th May 1949, when HKV 500 was driven by Ron ‘Soapy’ Sutton at 132.6mph. That was a simply remarkable figure for a sports car at the time, and now Jaguar was planning to put it into series production. The timing could not have been better, with the US market desperate to get its hands on British sports cars after the Second World War.

Such was demand that the XK120 was forced to go from limited to full production, which meant a switch from aluminium-over-ash to steel for the main bodywork in April 1950. The range was broadened too, with a delightful fixed-head coupé arriving in 1951 and the pretty drophead coupé in 1953.

Sure, the XK engine isn’t perfect – it did like a slug of oil on a pretty regular basis in the early days, and never did its business without liking a decent slurp of fuel either, which is why the AJ6 was developed. But it powered Jaguars for over four decades, found uses in the military world and, most importantly, found fans all around the world. People fell in love with its low-down pulling power, its punchy mid-range and the glorious noise – not to mention the fact that with the earlier cam covers, this remains a beautiful engine just to look at.

The fact that you could buy a road car, from sporty XK or E-type to luxurious saloons with the ‘same’ engine that had won Le Mans several times was the icing on the cake. Sure, those race engines were substantially tweaked for power, but the growl of a D-type can be heard even within the refined confines of a Daimler DS420. It’s the sound of genuine heritage, and a very exciting one.

Jaguar XK engine: the landmark vehicles

Jaguar XK120

Built in November 1953, towards the end of XK120 production, this is one of just 107 Open Two Seaters built for the right-hand drive market that year.

To this day, the XK120 is a remarkably pleasant design, and one which turns heads everywhere you go. There is such delicious purity to the design, with very little to spoil the lines. The dainty bumpers, lack of indicators and spats over the rear wheels create a clean shape that’s still achingly pretty. But, the beauty extends under the bonnet, where the XK engine looks beautiful and purposeful at the same time. It’s the perfect hand to fit in this stylish glove.

Tellingly, Jaguar Heritage volunteer Christian Sharland, who was fortunate enough to be driving the car said, “It’s just so nice to drive. It just doesn’t feel like a 1953 car.” That’s probably due to the refinement, meaning that time at the wheel is not jarring and uncomfortable. The suspension is supple and the huge reserves of torque from the XK engine mean progress is effortlessly brisk. There’s no need to extend the engine to make good progress, though one always has to remember the limitations of those drum brakes: use them harshly through a sequence of bends, and they can still begin to fade alarmingly.

Daimler DS420

Jumping straight to the end of the XK story now, the very last car built that used XK power was the final Daimler DS420. Following Jaguar’s purchase of Daimler in 1960, the DS420 was the only new design not shared by both companies. The Daimler badge and grille would be used on plusher versions of Jaguar’s saloons right up until 1997, but the DS420 had no Jaguar equivalent.

There’s plenty of Jaguar within though, as the structure is simply a lengthened MkX. The rear styling was developed at Browns Lane, where Lyons maintained a keen eye on the project, having successfully lobbied within British Motor Holdings for the Daimler to be the chosen project, ahead of in-house rival Vanden Plas.

As it was, DS420 final production initially took place at the Vanden Plas works in London, but all elements were moved to Browns Lane in 1979, when the Vanden Plas works was closed down. Just over 5000 were built, with over 900 in chassis form to become hearses.

The DS420 here is the very last one built, one of just 22 in that final year – a far cry from the 428 of 1970. It is also the final car built with an XK engine and was kept by Jaguar, passed straight to the Heritage Trust on completion. That may explain the slightly-odd specification, which includes manual windows all-round, and a rather eye-catching metallic red paint job, in stark contrast to the sombre tones of most. The drinks cabinet inside was added later, constructed at Browns Lane and perhaps to give a more exclusive feel to the interior.

Given the choice of travelling to the photoshoot aboard the windswept XK or the capacious Daimler, I must concede I chose comfort. I soon settled into the part, atop the luxurious rear bench. The ride is as pleasant as you’d expect, though the XK engine is more vocal than seems ideal. It never seems to be working too hard, even as it briskly gathers pace, but it is always makes its presence known.

The interior is a remarkable mixture of old and new worlds, though. There is a mixture of 1960s switchgear, and 1990s. The centre of the dashboard is pure MkX, but with a 1990s cigarette lighter in the middle. The driving compartment is quite cramped, but that’s all the better for the motoring editor sitting in the back, who can truly stretch out his legs.

Jaguar Mk2 3.8

Representing the compact saloons, Terry Birt’s Jaguar Mk2 3.8 MOD more than fitted the bill. Originally, the powerplant was meant to be the four-cylinder XK engine, but when Jaguar put the 2.4-litre into production in 1955, it had opted for a smaller version of the six-cylinder powerplant.

When the compact saloon evolved into the Mk2, things got even better, with the largest 3.8-litre version now offering a stunning 220bhp SAE. Compact it might be, but the Mk2 was not short of power in this form and it built up a reputation as one of the finest sporting saloons

These are still exciting cars to drive, and seemingly in demand like never before. Sure, the legendary XK grunt is a huge part of that, but credit must go to Lyons, for skilfully turning Mk1 into Mk2. The slim pillars and curvaceous lines combine to create one of the most handsome Jaguar saloons of all time.

The Mk2 was the real volume car for Jaguar, selling over 90,000 units including the later 240/340, but not the V8 Daimler version.

Jaguar E-type 3.8 FHC

Given the sensation that was created when the XK120 was launched, following on from it would take something special. The evolution of the XK line hadn’t really done more than just keep that formula going, but the E-type broke new ground. Choosing a completely new body construction type, and vastly different styling was certainly a bold step, though one confirmed by the work of Malcolm Sayer with the D-type race car. This remarkable machine used monocoque construction and smooth lines to help it do better with its relatively feeble XK engines than the heavier, more powerful V12 Ferraris.

Again, it’s the cleanliness of the lines that really do the shape justice, from the smooth open grille, to the dainty front and rear lamps, and those delicate bumpers. The row of three windscreen wipers is just the icing on the cake.

The E-type’s skills were not just skin deep though. At the rear, new independent rear suspension boosted handling without compromising ride, and this design would soon be fitted to the saloons too.

While friendly relationships with the press and possibly-tweaked test cars helped promote the myth of the E-Type being a genuine 150mph car, it was the looks that really sold it. That and price. Wily Lyons, as ever, didn’t push the price up too high. Whether the E-type actually delivered effective profits is an argument for another day, but it certainly helped maintain Jaguar’s reputation for sporting excellence, even as the E-type gently evolved into rather less pretty versions of the original.

Alvis Scorpion

Yes, you may have noticed that one vehicle in this group rather stands out. It’s an Alvis-built Scorpion Combat Vehicle Reconnaissance (Tracked) or CVRT. Well, we couldn’t get together a group of XK-powered vehicles without something a bit different.

Different this military vehicle certainly is, being the only one of our five that is front-wheel drive for a start. The engine actually sits back-to-front, to drive the seven-speed gearbox and front-most wheels in those impressive tracks. There is also a gun, though it’s quite small in, er, tracked military vehicle circles. I’m trying desperately not to call it a tank, because otherwise owner Andrew Baker will tell me off, and if I’ve learnt anything in life, it’s don’t upset someone who has a, er, tracked military vehicle.

But how did the XK engine end up in a military vehicle? It turns out the military had a fleet of MkIX saloons, and took the engine out of one to try in a prototype military vehicle. The military-spec already included special pistons to reduce the compression ratio to 7:1 and allow it to run on poor fuels. The trials were successful, and led to the 4.2-litre engine being used in a range of vehicles. It wasn’t Jaguar’s first military experience – it had developed a V8 for military use prior to this, but it wasn’t taken beyond the prototype stage.

Andrew has owned the Scorpion for around 18 years, since it was de-mobbed. It has been fully rebuilt, including the XK engine, the transmission, tracks and wheels, though it still has its night vision equipment, even if the gun has now (thankfully) been decommissioned. Remarkably, Alvis built about 3500 vehicles in this family, of which the FV101 Scorpion is just a 300-odd part. There is the similar Scimitar, Sultan command vehicle, Samaritan ambulance, Striker anti-tank guided missile platform and the Samson armoured recovery vehicle.

To fit in the transport planes of the time, there was a width restriction, which ruled out fitting a vee formation engine. With Alvis being sited in Coventry, it looked locally for a solution, and opted for what is known in military circles as the Jaguar J60 engine. Fitted with a single Solex carburettor, the J60 produces around 195 bhp, enough for a top speed of around 50 mph. Pretty brisk for eight tons of CVRT. Andrew also reckons the brakes are Jaguar items, with them being necessary to make the skid-steer system work. Rather than a steering wheel, the driver pulls on two brake levers to stop, or one to turn. The right foot operates the throttle, while the left operates a gear-change pedal.

Scorpions notably saw action in the first Gulf War, but by the time of the second, Scorpions (and others) still in use were converted to Cummins diesel engines. No Scorpions remain on the British Army fleet, though many of its siblings do.

As the Scorpion accelerates, there is a great cacophony of noise, from the tanks and transmission especially. Yet, there is a growling petrol engine in there with a recognisable beat. Few could have imagined in 1948 that the XK engine would be powering military vehicles in the 21st century.