A large saloon intended to capture the hearts of American buyers, the Jaguar MkX is an undervalued classic today. We take a 1966 example for a spin

Words: Sam Skelton

For Britain in 1961 there was no more influential place than America. We wanted their music, liberal lifestyle, clothes and cars. Even Jaguar – conservative despite its image as the spiv’s Bentley – was briefly captivated, and in that year unveiled the MkX. Coventry’s new flagship owed more in its proportions to Cadillac than to previous Jaguars, and was loved neither in its US target market nor in Mini-Minor Britain.

This wasn’t how it was supposed to be. After all, the smaller Jaguars had been selling well in America, as had its sports cars. While its biggest saloon the MkIX still resembled the MkVII of a decade earlier, that car had caused a sensation in the States too. It seemed that a new big Jaguar would sell equally well, especially if it followed the same stylistic trend as its smaller siblings. Four headlamps were incorporated as a sop to American mores, while the whole thing looked more like an airbrushed brochure image than a real car with its exaggerated proportions.

Development work had begun in 1958, when Jaguar’s range encompassed the small MkI saloon, the large MkIX, and the XK150. The new car, codenamed Zenith, was to replace the MkIX and to take advantage of MkI style unitary construction to save weight. It sat on the same wheelbase as its predecessor, though the front track was slightly wider and the whole car sat over 8” lower. The body was 3” broader, but much of this was contained in its rolling flanks. Despite the aim of reducing weight, the MkX weighed 4.5% more than its separate chassis predecessor according to Autocar, no doubt as a result of Jaguar’s desire to ensure total solidity. Contemporary testers surmised that, given body maker Pressed Steel Fisher’s track record with the MkI, Jaguar had designed in enough stiffness to ensure that PSF’s quality control measures wouldn’t allow an inadequate car through.

Overall, the press liked the car. Its independent rear suspension design would go on to be imitated by Jaguars including the S-type, XJ and XJ-S right through to the mid 1990s, while its styling was deemed purposeful even when at a standstill. Autocar found no evidence of rattles, and felt its stability to be akin to the best sports cars – while its interior ambience was akin to an Edwardian library. However, Motor found fault with Jaguar’s soundproofing, quality and ventilation, though couldn’t fail to praise its space and dynamic abilities. While Motor was forced to apologise to Jaguar, there was no undoing the serious nature of the complaints in the original report.

Plans to fit a 5.0-litre version of the V8 from the Daimler Majestic Major were abandoned; in part because its performance would have embarrassed the supposedly more sporting Jaguars and in part because the Radford plant’s capacity for V8s had been reached. But while the press continued to sing the model’s praises, especially after the launch of the 4.2 litre variant in 1964, the public simply wasn’t buying the car. The Americans at whom the MkX had been targeted found it too expensive to compete by the time it had been imported, while here in Britain it was just too big even alongside cars like the Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud.

Just 25,211 MkXs and 420Gs were sold in the model’s eight year life – one MkX left the showroom for nearly every five MkII-derived models. It seems hard to comprehend in 2021 just how badly Jaguar misjudged its target audience. But while Jaguar had hoped to tempt US businessmen away from their Cadillacs, it was in vain. By 1963, Jaguar’s American distributor had taken to calling the car “the lemon”.

Back in Britain, it was a similar story. Those who had loved their MkIXs were terrified of the sheer size of the new car – until well into the new Millennium it was the widest car Britain had produced, at over 6’4” from flank to flank, and 16’10” long it would take Jaguar 34 years to launch another flagship model of quite such gargantuan length in the shape of the long wheelbase X300 XJ. Leaving aside the sheer size of the thing, the nation which would soon become Wilson’s socialist Britain favoured more parsimonious transport like the Mini and the Ford Cortina. It took bravery to endure the social opprobrium of being seen in the biggest car on the road so soon after the Suez Crisis had caused petrol rationing, and those who could afford it preferred not to advertise the fact quite so flamboyantly.

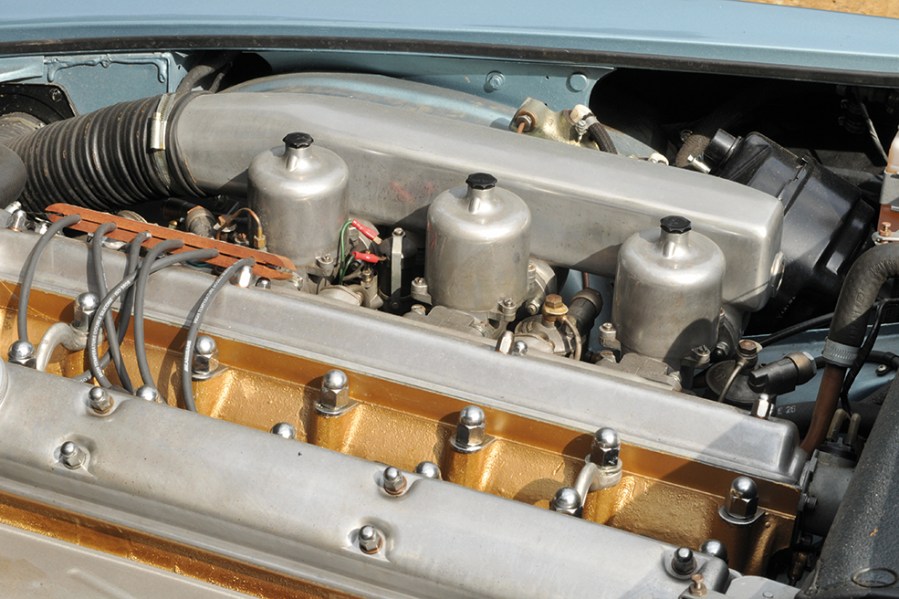

Ordered new by the likes of the Kray twins, T. Dan Smith, Angus Sibbet and Ken Dodd, who would have paid £2291 in 1964 – which would have bought you an E-type and change – the MkX came with the same XK engine as the E-type, initially in 3.8-litre form but succeeded by the torquier 4.2 in 1964. While the E-type gave you speed, the MkX gave you a boot big enough to carry a spare car should you break down, along with comfortable accommodation for half a dozen six footers in the cabin.

To try to shore up flagging sales, Jaguar updated the MkX for 1966. It got a new name – the 420G – new hubcaps, indicator repeaters on the wings, a padded dash top, and chrome swage trims to try to disguise the excessively bulbous body. But it wasn’t enough. Jaguar chose to slim down its confusing 1960s model range into a single saloon for 1968, the XJ – and the 420G was the only model to survive this rationalisation.

The 420G was produced until June 1970 – but by then sales really were slow, with only about 30 MkXs per week being sold from the end of 1969 onwards. By then, prices sat only just above those for the XJ6 4.2, which was the Jaguar saloon everybody wanted. Nobody mourned the loss of the 420G when Jaguar withdrew it – Browns Lane replaced it two years later with a long wheelbase version of its new XJ12 saloon, but it didn’t make the mistake of courting America so slavishly again.

Interestingly, the MkX did sire the company’s longest-lived single model, and the one which saw the XK engine soldier on into the 1990s – the Daimler DS420 limousine was based on a lengthened variant of the MkX floorpan, and the drivetrain was taken lock, stock and barrel from the giant Jag.

As the MkX turns sixty, it seems that it’s only fair we re-evaluate it away from the context of its market failure, and look at the car as the classic it has now become. So we borrowed this Opalescent Silver Blue example from friend of Classics World and classic car dealer Kim Cairns, of Snettisham, Norfolk. It’s a 1966 4.2, which just predates the changeover from MkX to 420G. Kim also had a dark green 420G in stock, and two more MkXs in his workshop – we had scoured the country looking for one for our road test and then four turn up in the same location! At our first stop of the day, we were approached by an admirer – and this set the tone for a photoshoot interrupted by several members of the public expressing admiration for the car which was so reviled when new.

From the moment you open the door the solidity of the Jaguar is made abundantly clear. Before you settle down on the individual sofa that is the driver’s seat, you have to navigate a sill that’s several inches wide. Once in, it feels like any other Jaguar of its era might feel to a Borrower – there’s the same exquisite woodwork in front of you, the same Smiths gauges, the same lovely soft leather – but instead of everything falling closely to hand as it does in a MkII, it’s all a stretch away. Once belted in, it can be hard to reach some of the minor controls in the centre of the dash including the vital fuel tank switch. Turn the key and press the starter button – if you can reach it, and the familiar XK starts. There’s nothing here that’s new to 1960s Jaguar drivers, except the sheer size. Put it into D and set off, and this is where things begin to deviate.

Navigating the roads around the Sandringham area, you’re always deeply aware of the sheer size of the car – in a way that more modern Jaguars of similar proportions manage to hide from the driver. Perhaps it’s the fingertip light steering that confers the sense of sheer size – in a car with more weight to its controls, you have to focus less upon keeping it exactly where you want it to be, where the MkX will willingly respond to the smallest of inputs.

Perhaps it’s the tumblehome nature of the body, meaning that from the cabin you’re never quite sure where the extremities of the wings sit. But as you get used to placing the car on the road, you begin to appreciate the qualities that Autocar raved about back in 1961. The ride, for instance, is utterly faultless, a combination of a large footprint and well-designed suspension making this every inch the equal of anything this side of a Citroën DS.

0-60mph in a smidge over ten might not seem quick today, but remember that it’s a sixty year old design weighing in at almost 1900kg, pushed along by a three speed automatic box. Performance that could shame sports cars like the Triumph TR4 and MGA Twin Cam was nothing to be sniffed at; and rivals such as the Bentley S1 toward whose customers Jaguar aspired were left standing at around 100mph on the M1, when the Coventry Cathedral on wheels could blast past at a quarter as much again.

For a car of its size it turns in sharply, and while you’ve little feedback through the steering the grip ensures you’re not going to get into any sticky situations unless you’re driving like Ronnie and Reggie with a boot-load of bullion. But while the MkX will keep you out of trouble, it’s far better to keep yourself out of trouble by slowing down and wafting, sitting back, enjoying the atmosphere and the admiring looks. Our colleague Paul Wager said as we were shooting the car that “it’s the sort of car you could sit back and drive all day, if you could afford the fuel” – and it’s as an A road cruiser that the big Jag excels.

And the MkX has always been the forgotten Jaguar saloon – overshadowed by the earlier separate chassis flagships, passed over for the later XJ, and ignored in favour of MkII derived models with their Great Train Robbery cool. This means that the MkX has always been cheap, and so many of the 25000 originally made have been cut up to provide engines for E-Type restorations or scrapped because restoration wasn’t financially viable. This makes them exceptionally rare today – we spent weeks searching before we found this car to test.

And values, relative to other 1960s Jaguars, are criminally cheap. The car which embodies Grace, Space and Pace like no other Jaguar can be had from as little as £10,000, and even the very best examples struggle to fetch more than £30,000 in today’s market. Contrast that with the MkII, with dealers asking up to £100,000 for the very nicest 3.8s and £40,000 being the norm – even a 2.4 will outsell the best MkX. MkX values haven’t risen as significantly as other 1960s Jags, but that means they’re due to go up in the near future. It could, on the eve of its 60th birthday, prove to be a canny investment.

Finding rivals to the MkX is difficult, as by dint of its size there are few which could match it at its price point new. On the same day we tested the car pictured we drove a Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud, which by comparison to the Jaguar felt narrow and easy to thread down country lanes. It’s a genuine six seater too, so rivals are best selected from Detroit – at which point you lose the gentleman’s club atmosphere. Arguably the closest alternative would be something like a Lincoln Continental, though arguably even that is more visually restrained than the big Jag.

Let’s face it, if you’re interested in a MkX nothing else will do, so it’s pointless to list alternatives. Despite its many flaws, the MkX is astoundingly good value and makes you feel special, both of which make it a compelling classic purchase today.