So much more than a stopgap, the short-lived Triumph TR5 is now arguably the most sought-after model in the TR range. Here’s how to buy a good one

Words: Jeff Ruggles Images: Simon Goldsworthy

The TR5 simultaneously marked the end of one era and the beginning of another for Triumph’s TR range, retaining the handsome Michelotti-designed body of the TR4 and TR4A but with a more powerful six-cylinder punch that paved the way for its TR6 successor. Manufactured from July 1967, the TR5 was a one-year wonder, but its relative rarity and ‘best of both worlds’ slot in the range means it’s a highly desirable classic.

In truth, its roots extend back even further than the TR4 of 1961, as that had essentially taken the underpinnings of the TR3 and clothed them in a new body. A big change came in 1965, however, when Triumph unveiled the revamped TR4A. These were badged ‘IRS’ in reference to a revamped rear-end chassis set-up that allowed the fitment of a fixed differential unit and fresh mounting points for the semi-trailing rear suspension – which now used coil springs.

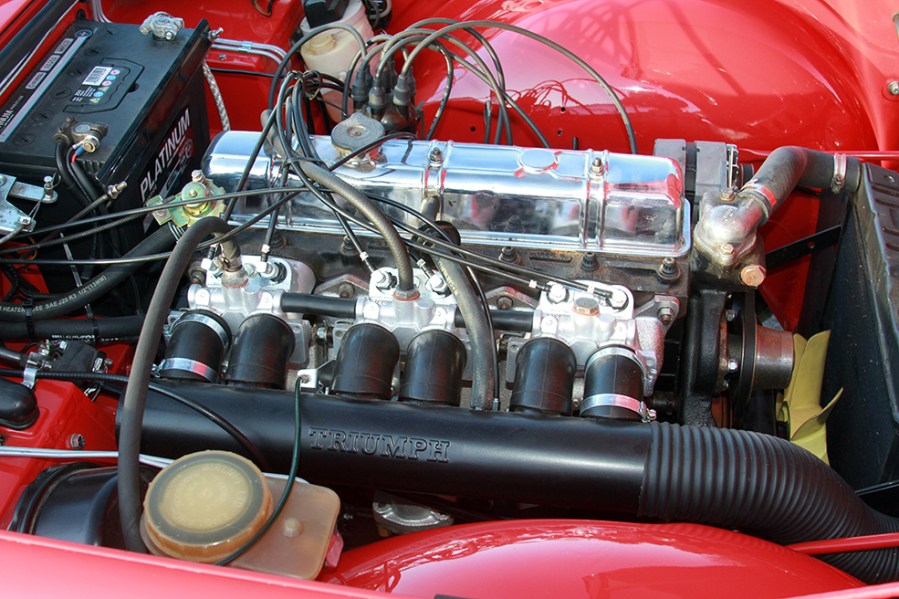

After the body change and suspension change, it was the TR5 that ushered in an engine change that gave it genuine sports car performance. As well as receiving two more cylinders and a capacity boost from 2138cc to 2498cc, the new model gained Lucas fuel injection. However, the TR5 couldn’t be sold in North America because of the USA’s new exhaust emission regulations. Instead, there was the TR250, which had a 104bhp version of the six-pot with twin Stromberg carbs. This was the first and only occurrence of a separate TR name being used for such markets.

September 1968 would see the end of production for both models, with fewer than 12,000 produced in total. However, survivor numbers remain healthy. Here’s what you need to know when looking for an example for this iconic British sports car.

The US-spec TR250 was made in far greater numbers than the TR5 – 8484 cars to 2947. Do note, however, that the carburettor engine is not only less powerful and rear axle ratios were lower to compensate, plus they are left-hand drive of course. On this note, converted cars tend to be worth a bit less than a home-market TR5.

Before buying, make sure that you’re acquiring a proper TR5. Because they are worth more than TR4s and TR4As, it’s not unknown for a six-pot engine to be dropped into a TR4 and passed off as a TR5. A TR5 chassis number will start CP, while CT means it’s a TR4, CTC is a TR4A and if it’s a TR250 it’ll start with CD. The commission plate is located on the nearside front inner wheelarch.

Bodywork

Panel alignment is the first thing to check. Gaps should be uniform, and if they’re not, accident damage, a drooping chassis and/or poor repairs could be the culprit. Corrosion can strike pretty much anywhere, but pay particular attention to the A and B posts, floors and sills. There may be a separate chassis, but sills are still vital to hold the body together properly. New Heritage sills cost around £110 each, but that bill can zoom up to £1200 per side once you factor in the inevitable further restoration work as rot is chased out of the floor, plus preparation and paint. Door fit is the real giveaway to how well a restoration has been carried out. If they’re difficult to open or close, that’s a mark against the car.

Other areas to check for rot include the battery tray and bulkhead, all four wings – both inner and outer up front – the boot floor and sides, the bootlid lip, the front panel and the bonnet skin. Look carefully for bubbles in the paintwork that hint at corrosion beneath, and make sure the beading is in place in the seams between the top of the rear wings and the deck; it’s sometimes substituted for filler during a restoration.

Ideally, you need to raise the vehicle so the chassis can be inspected, as although it’s a sturdy affair, it can still corrode. The front is usually protected by leaked engine oil, but you need to check for stress cracks around the suspension mounts as well as kinks from accident damage. The rear is more of an issue, though: Inspect the chassis all around the suspension and differential mounts very carefully. Watch also for rot in the front crossmember, gearbox and engine mounts, and outriggers.

Engine and transmission

The six-cylinder suffers from heavy wear to its crankshaft thrust washers, not helped by disengaging the clutch for long periods in traffic. This causes a drop in oil pressure and can result in costly internal damage. Check by getting someone to depress and release the clutch pedal while you watch for fore-and-aft movement of the bottom crankshaft pulley. It should be barely detectable at worst.

Also check the engine for coolant leaks and a rough tickover, and perform a compression test if possible. The fuel injection has had a bad press over the years, and is prone to running rich to the detriment of fuel consumption. As so often though, many of the issues stem from poor maintenance and lack of understanding of the system. It works well if set up properly and can be made reliable.

Before consulting the experts though, there are simple DIY checks you can make. The system relies on both engine vacuum and ignition timing to function properly, so check the timing is spot-on and that the vacuum hoses are intact and connected. It’s also useful to check that the valve clearances and camshaft timing are set correctly. A common modification is to use a Bosch injection pump in place of the barely sufficient original and a fuel pipe coiled to increase its surface cooling area, which helps cure troublesome vapour locks.

Transmission-wise, the four-speed gearbox is a refined unit, but any excessive whining or jumping out of gear when on and off the throttle is bad news and signals the need for a rebuild. Overdrive was a factory option, with the Laycock A set-up operating on second, third and fourth. It can be retro-fitted, but this can be an expensive job, and beware of weaker saloon car overdrives being used that only work on third and fourth. If the overdrive won’t engage, it’s often just an electrical fault or even low fluid in the gearbox. Note that overdrive on TR250s is very rare.

Meanwhile, baulking when changing gear can be down to the clutch hydraulics not being bled properly. Sometimes the slave cylinder is fitted upside-down, so the bleed nipple faces in the wrong upwards direction.

Suspension, steering and brakes

Listen for a noisy differential, which could need reconditioning or replacing. The propshaft and driveshaft universal joints can wear too, so listen for clonks. They’re not hard or costly to replace, but wear in the driveshaft splines is more expensive. Upgraded replacements are available that are more durable.

The steering should be free of play and be very accurate. A worn rack will cost around £100 to replace, but note that the TR5 used rubber rack mounts, which degrade and allow some sogginess to creep in. A worn rack usually creates clunks, but free play is usually down to tired trunnions. These need regular attention with a heavy oil – not grease – and can seize if they’re not lubricated properly. This then puts a strain on the suspension, mainly the drop link on the wishbone.

All TR5 and TR250s had the independent rear suspension set-up – the state of the large trailing arm bushes and the security of the metal around the mounts should be carefully checked. Also check the dampers for leaks, and pay attention to the rear hubs. Any play means they’ll need replacing.

Braking is courtesy of discs at the front and drums at the back. Make sure the car pulls up swiftly without pulling to one side. Handbrakes were always on the feeble side so don’t worry if it seems a little weak, but do leave the car in gear when parked.

Interior, trim and electrics

All interior trim is available on a reproduction basis, while cracks or discolouring to the wooden veneered dash can be sorted within the scope of a keen owner. Plastic dash tops and the lower padded crash bars can crack and wrinkle with age, but replacements are available.

Everything can be also bought to fix any electrical issues, but be wary if the windscreen wipers don’t work properly – motors can be easily replaced but replacing a tired or seized linkage entails removing the dashboard for access. Carpets need checking for dampness – expect a £200 wallet hit if it needs replacing.

Both the TR5 and TR250 were offered as soft and hard top models. If a soft-top hood is worn, you can expect to pay £250-£600 for a replacement depending on what material you fancy. The hardtop cars had a fixed rear window and a removable metal roof section. This set-up is often referred to as a ‘Surrey Top’, but in fact that nametag only originally applied to an optional fabric section that could be used in poor weather if you had left the main roof panel at home. On cars equipped with a hardtop, take a look at how neatly the panel fits and check the seals are in good condition.

Triumph TR5: our verdict

The TR5 is the most expensive of the TR range, but it is a particularly tempting package with its rounded good looks and excellent performance. The short production run ensures exclusivity, but there’s excellent parts availability thanks to the number of parts shared with other models, and strong club support from the likes of the TR Register. Of course, there’s also the option of the TR250, which can be tuned to give similarly strong performance and is generally more affordable. Either way, you’re getting a muscular sporting icon with established classic credentials and a strong helping of aural pleasure.

Due to its rarity and performance, the TR5 tends to command higher prices than its TR4/TR4A predecessors and its TR6 successor. Prices rose during the middle of the last decade and seem to have returned to similar levels after a lull, meaning than example that’s useable but in need of work is likely to cost around £20,000, and one that’s in excellent order but not concours costs around £40,000. For immaculate cars, expect to pay north of £50,000. TR250s tend to be cheaper, with the best examples usually available for under £40,000.

Triumph TR5 timeline

1967

The TR5 supersedes the TR4A, with a fuel-injected straight-six. North American cars have twin carburettors and are badged TR250.

1968

TR5 production ceases ahead of the TR6 launch.

Production of the TR6 begins in September