The missing link between traditional Saabs and GM cars, the first-generation Saab 9-3 was the last Saab-engined model. Here’s how to buy one

Images: Paul Wager

The world of late-model Saabs can be a confusing place, with the original Saab 900, the ‘new generation’ GM 900 and the first of the 9-3 models all looking at a glance very similar. Once you take a closer look the big bumpers of the classic 900 single it out, but the late-model 900 and the early 9-3 are so similar apart from the rear plate repositioned between the lights that it’s generally assumed they were simply a badge-engineering exercise.

According to Saab back when they launched the original generation (‘OG’) 9-3 in 1998 though, it was far more than a rebadging exercise, the Swedish maker claiming that over 1100 changes were made. Chief among them was a revised suspension to counter criticism of the earlier 900’s rather uninspiring handling, the 9-3 gaining sharper steering, 20% more wheel travel, raised suspension turrets and revised struts.

The uninspiring handling was a legacy of the General Motors platform on which the 9-3 was built, which also underpinned what we know in the UK as the Mk3 Vauxhall Cavalier and the first-generation Vectra. The 9-3 naturally retained the GM platform but in finest Saab tradition the Trollhättan engineers couldn’t resist improving it, notably by improving crash safety courtesy of stronger pillars, sills and doors.

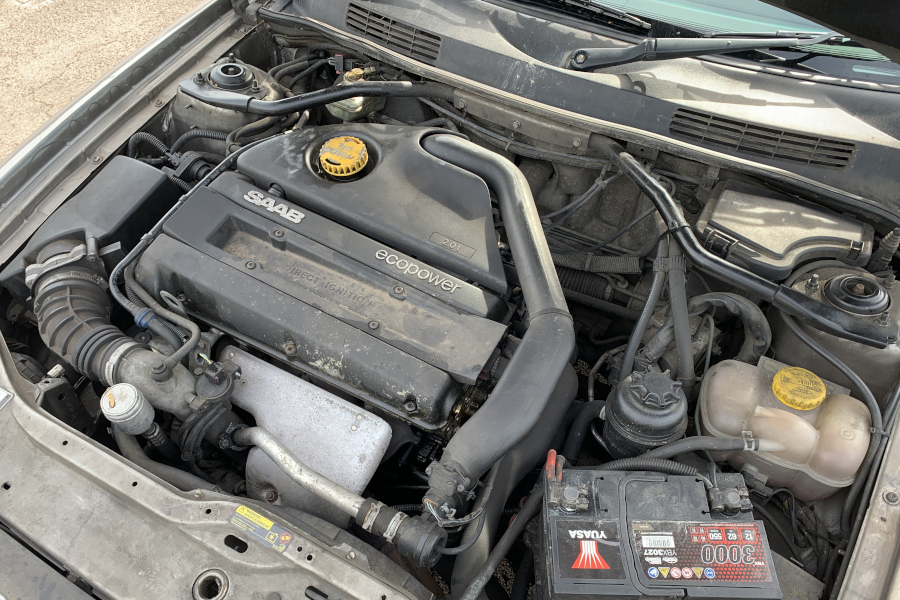

As with the previous 900, the 9-3 used a transverse engine layout but retained the Saab engine, this being the ‘H’ block which shared only distant memories of the Ricardo/Triumph unit of the ’70s from which it had evolved. Driving through a conventional gearbox rather than the unusual gearbox-under-engine layout of the longitudinally engined classic 900, the 9-3 was front-wheel drive and in most respects was pretty conventional.

On the inside some signature Saab quirks survived, including the reverse gear ignition lock, the ‘night panel’ supposedly derived from fighter jets which cut out all the instruments except the speedo and those curiously shaped headrests which actually use an innovative anti-whiplash pivoting mechanism. Plenty of Vauxhall switchgear was in evidence but the 9-3 was nicely put together, as befitted a brand with ‘junior prestige’ status nibbling as it was at the toes of BMW.

At launch, the 9-3 was offered in both three and five-door form with the 2-litre engine in naturally aspirated 130bhp form as the 2.0, 2.0S and 2.0SE, with the 150bhp 2.3-litre engine offered in the 2.3S and 2.3SE. The 185bhp turbocharged 2-litre was also offered as the Turbo S and Turbo SE. The five-door meanwhile was offered with Saab’s first diesel engine as the 115bhp 2.2TiD in basic, S and SE specification.

The convertible was also given the 9-3 makeover, the range including 2.0S, 2.0SE, 2.3SE and the 2.0 Turbo SE.

The move to GM platforms may have tamed the quirkiness for which the brand was famous, but the Swedes weren’t entirely crushed by their new American overlords, as the 9-3 Viggen proved. Developed with assistance from TWR here in the UK, the Viggen (Swedish for Thunderbolt) used an uprated high-compression version of the 2.3-litre turbo engine from the bigger 9-5, running more boost from a bigger turbo and with a bigger intercooler, revised exhaust and remapped ECU to produce 230bhp and 258lb.ft. The transmission received a beefed-up gearbox casing, clutch and driveshafts, while the Viggen sat on lowered and uprated springs with firmer dampers and revised anti-roll bar.

Offered only as a manual, the Viggen was famed for its rapid if rather unruly pace, the chief impression it left with most road testers being its dramatic torque steer. As Saab tuner Ed Abbott recalls, the car could leave a 20-metre long stripe of smoking rubber from the unloaded inside front wheel and on bumpy surfaces was hard work to control, even with the electronic torque reduction in the lower gears fitted to preserve the gearbox. Curiously, the US importers fitted standard traction control while it was optional in the UK.

In 1999, the engines were given the newest version of Saab’s own electronic engine management, Trionic 7 and the non-turbo engines were dropped. Renamed the B205 and badged Ecopower, the 2.0 ‘low pressure’ turbo was good for 154bhp as the 2.0t or 2.0t SE, while the 2.0T SE managed 185bhp and the full fat version in the range-topping Sport (renamed Aero from 2001 and often known as the High Output Turbo, or HOT engine) produced 205bhp. Meanwhile, the 2.2litre diesel was uprated to 123bhp.

In summer 2003 the first-generation Saab 9-3 was replaced by an all-new second generation which finally severed all ties with Saabs of old, powered by a range of GM engines and remaining in production until Saab itself closed its doors.

Today the 1998-2003 Saab 9-3 represents incredible value with respectable examples around for well under £1000, but should you be wary of buying a performance car from a brand which expired over a decade ago? Read on and find out.

Bodywork

Saabs were traditionally built to withstand the Scandinavian climate and the same is true of the later models like this, but with the youngest now 20 years old it’s not unusual to find examples where our British winter road salt has started to make itself known.

Bubbling wheelarches and festering stone chips will be obvious and the four-door cars can suffer from rust in a panel joint behind the rear doors, just behind the side moulding. It’s worth checking inside the door shut to get an idea of how far it’s spread. Otherwise these cars tend to last pretty well and are certainly as robust as contemporary BMWs.

One big issue though stems not from corrosion but from a Saab design flaw. Both the GM900 and the first-generation 9-3 have the steering rack mounted on the bulkhead and the flexing can cause cracking. Back in the day this was a known problem with the convertible models and many were repaired under warranty, with Saab even supplying a repair plate for the purpose.

It’s reckoned by Saab specialists that as the cars have aged, all the Saab 9-3 models could suffer with the problem so it’s worth checking for visible cracking and also whether the pedals move when the wheel is turned. It’s not a massive welding job to sort the issue but there’s a fair bit of dismantling involved.

If the car seems sound, it’s reckoned that the steering rack mount brace sold by Abbott Saab will prevent it happening and will have the side effect of sharpening up the entire driving feel.

Elsewhere, look for the usual old car issues like tired gas struts, dropped doors and missing trim. In the case of Saabs though, be aware that some trim details can be hard to source, with used parts your best bet. Indeed, we even 3D printed some trim bits for our own 9-3 project car.

Engine and transmission

With its chain-driven cams and long development history, the Saab engine is a tough unit which if maintained properly can cover big mileages without catastrophic failure.

They do tend to be a bit oily in old age though, with several minor leaks combining to look unsightly. Suspect the usual culprits like the cam cover, although the early Saab 9-3s were known back in the day for the cylinder head bolts loosening and causing oil leaks. The dealer fix back then was to re-torque the bolts to spec and it’s worth doing that as a first step. Oil can also seep from the exhaust camshaft at the end of the cam cover and an aluminium bung and O-ring is available to seal it.

On the subject of oil, it’s reckoned that the turbo engines are happiest on a diet of fully synthetic and tend to suffer from sludging up when anything else is used, or simply when changes are neglected. This can lead to the oil strainer in the sump getting blocked and oil pressure dropping significantly – which in turn can lead to noisy cam and balance shaft chains.

Remember, most of these will be running a turbocharged engine, so make the usual checks for white smoke and the tell-tale whistles which point to boost issues. In extreme cases a replacement turbo is around £500 and fitting isn’t a massive job.

Turbo engines also use the direct ignition system rather than a distributor, but unlike conventional coil-on-plug systems from other makers it’s not possible to buy an individual coil, meaning you’re stuck with the £250 cost of the DI cassette. It’s also recommended to replace all the plugs at the same time, so a car with a misfire can be unexpectedly costly to sort out.

If you want to know which version of the engine you have, then check the colour of the DI cassette: it’s red on Trionic 5 engines and black on the later Trionic 7 engines. The non-turbo engines meanwhile use Bosch Motronic engine management with a conventional distributor.

If the performance on an earlier (Trionic 5) engine seems inconsistent, then suspect a failing boost control valve. These are no longer available but a manual bleed valve can be substituted and adjusted to suit.

Clutch life will vary depending on driving style but it’s generally reckoned that they’re not terribly long-lived. Replacement can be up to £900 at a general garage and if the pedal action feels very stiff then the job is on the horizon.

It’s also recommended to change the clutch hydraulic pipe at the same time, since the originals are known to split at the join between the rigid and flexible hoses. Abbott can supply an uprated part.

If the car jumps out of gear under acceleration or when lifting off, then be wary as rebuilds won’t be economically viable on a cheaper car. Dramatic movement of the lever when engaging the clutch in reverse however will simply be the rear gearbox mount which is easily sorted.

Despite Saab’s disappearance, service parts for the cars are still freely available.

Suspension, steering and brakes

Sadly, despite the claimed 1100 revisions which turned the GM900 into the 9-3, the handling in standard form is distinctly underwhelming and even when they were new was well off the pace of even a mid-range Mondeo.

It’s a soft set-up with plenty of body roll but also noticeable pitch and dive which is paired with a tendency for slightly unpredictable torque steer on the more powerful turbo models. Quality tyres will help, but even a well set-up example can be hard work to drive fast on a challenging road. The trade-off is that they feel pretty stable and comfortable at motorway speeds.

Upgrades are available, although specialists warn that simply fitting cheap super-stiff lowering springs will often make things worse. Abbott Racing has designed its own British-made springs which are 30mm lower than standard and just 20 per cent stiffer which are reckoned to transform the car, especially if paired with Koni dampers and the judicious use of polyurethane bushes.

Brakes on the other hand are perfectly conventional and any issues with seized calipers can be fixed with a remanufactured part.

Interior, trim and electronics

The Saab 9-3’s cabin has a distinctly Vauxhall ambience to it, not helped by the hard plastics but it’s nicely put together for the most part and problems are more likely to be a result of damage and neglect.

The standard column stalks are where the GM cost-cutting really shows: they feel cheap and are annoyingly noisy in operation but on the other hand they do seem to last. Like so many cars of this era, the pixels in the information display can start to disappear, but can be repaired.

The headlining was supposedly padded in the 9-3 as a safety measure but can tend to droop like an old Jaguar. It can be fixed up temporarily but will need replacement cloth eventually and this can be a satisfying DIY job.

High-mileage cars can suffer from the leather covering peeling off the gearknob and it looks terrible but is easily cured by pulling it all off. Similarly, the knob can pull away from the lever but a squirt of silicone sealant can fix it in place well enough while still allowing it to be removed. Remember to position it correctly so that the reverse gear lift-up collar still operates.

The standard-fit audio system isn’t the best but is integrated into the dashboard, so the best way to beef it up is to wire in a speaker-level amplifier. Audio channels or individual speakers can drop out, sometimes coming back to life after 10 minutes which indicates ‘dry’ joints inside the unit. If you’re handy with a soldering iron you can use a magnifying glass to find and reflow them.

Cars with the manual heater controls can suffer with the control shaft breaking off. The part can be replaced but expect it to fail regularly unless you dismantle the entire dash to access and lubricate the valve at the heater box end.

Parts

The big worry for most potential Saab 9-3 purchasers will be over parts supply for a 20-year old car from a marque which disappeared over a decade ago but having spoken to specialist parts suppliers it appears you don’t need to be too worried.

Marque specialist Saabits points out that service parts are readily available, while they can also supply repair panels for rot-prone areas like the rear arches.

Trim parts meanwhile aren’t too tricky, with some badging even still available from Saab’s successor parts company. The popularity of the cars in Europe and the USA means that there’s a sufficient market for parts to be remanufactured but some right-hand drive-specific parts can often be scarcer than their LHD equivalents for this reason. Having said that though, at the time of writing Saabits could supply a complete right-hand drive (genuine Saab) steering rack for just £80.

Certainly the situation for the first-generation 9-3 isn’t anything like as perilous as the last of the 9-5s. Built only in small numbers for two years, there’s a delightful urban rumour that no two are alike.

Saab 9-3: our verdict

The GM influence may already have made the cars more mainstream by the time it appeared but there’s still just enough Saab in the first-generation 9-3 – including the Saab engine of course – to make it an appealingly different choice while still being modern enough to use as a daily driver.

The Saab 9-3 is also as cheap as it’s going to get, with usable MoT’d examples around for well under £1000 and lovingly preserved enthusiast cars at the other end of the market.

Buy on condition, make sure all the tricky trim bits are present and undamaged and you’ll have a modern classic which will always be a talking point.

Saab 9-3 ‘OG’ timeline

1998

The Saab 9-3 is launched

1999

Engine range is revised, non-turbo models dropped. Choice of light-pressure 154bhp, the full-pressure 185bhp turbo or the 205bhp ‘HOT’ engine plus 125bhp diesel

Viggen announced with 230bhp

2001

205bhp model renamed from Sport to Aero

2002

The Viggen is discontinued

2003

The ‘OG’ 9-3 is replaced by the all-new model