Both were revolutionary, sub-10-foot monocoque city cars, but can the chic Fiat 500 hold its own against the faster, roomier Mini?

An influx of tiny, efficient microcars might have made sense amid a post-war drive for cheap personal transport, but for BMC supremo Leonard Lord, it presented an opportunity. With the backdrop of the 1956 Suez fuel crisis upping the ante, he promptly told Alec Issigonis to drop everything and design a proper small car that would drive the “bloody awful bubble cars” off the streets.

The Mini, or the Morris Minor-Minor and Austin Seven to give it its launch titles, emerged in 1959 as a proper four-wheeled car wrapped up in city-sized package less than 10 feet long.

But it had been comprehensively beaten to the post by a diminutive Italian in the shape of Dante Giacosa’s Fiat ‘Nuova’ 500, which had already been on sale for two years and was even shorter at just over nine feet. Admittedly the earliest 500s had only two seats compared to the Mini’s four, but that was quickly remedied. Besides, the blueprint for the 500 was even older, with the four-seat Fiat 600 – itself hardly a giant at 10 feet seven inches – launched in 1955.

While Issigonis went for a revolutionary transverse front-engine layout with front-wheel drive and the gearbox in the sump, Giacosa had opted for a rear-mounted 479cc engine driving the rear wheels. The 500 arguably had an even bigger impact on Italian transport than the Mini did in the UK, with its cheap price getting many off their scooters and on to four wheels for the first time.

Of course, both cars went on to be huge successes, spawning various derivatives and hot performance models, as well as being loved by people who normally wouldn’t give two hoots about cars. They even inspired the retro-styled current-day models we now see just about everywhere. But which makes the best classic buy?

Mini

The Mini was hugely inventive, but got off to a tricky start. Not only was it a bit too radical for the UK’s rather conservative car buyers, it had build quality issues. The early cars were effectively running prototypes, with the first buyers left to discover issues like weak gearboxes and incorrectly lapped floors that caused water ingress.

That could’ve been fatal, but its bacon was saved by trendy London types who wanted something easy to park. Before long, the Mini became a truly classless vehicle that appealed to everyone from blue-collar workers to film stars, and would go on to be built all over the world, from Cowley to Chile.

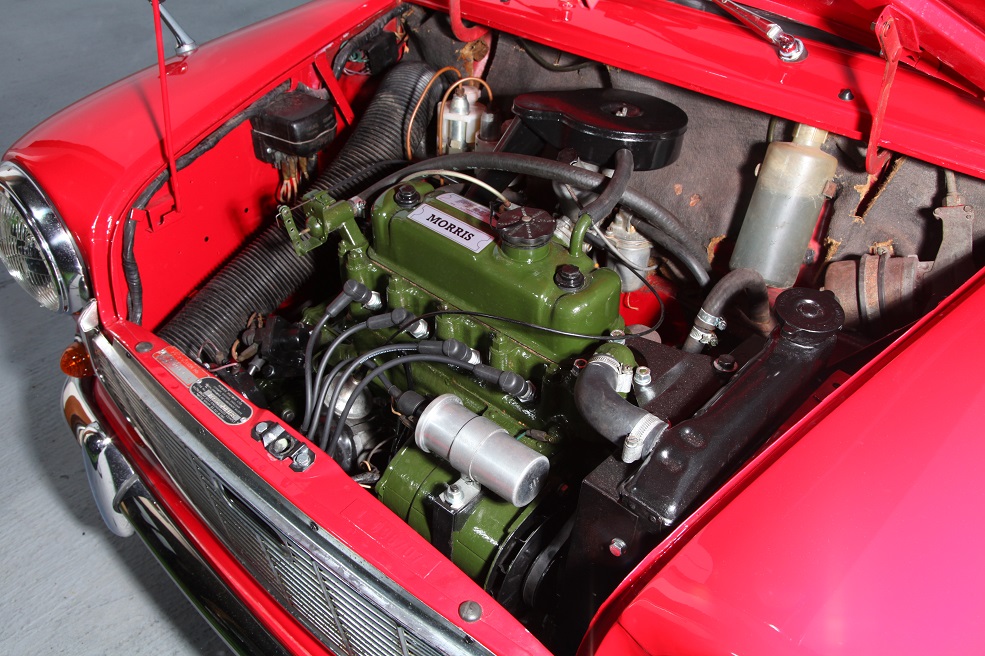

Another major plus was the car’s handling ability, which sent journalists into raptures. Before long the motorsport fraternity had cottoned on too, realising the car could handle more grunt than the 34bhp provided by its stock 848cc motor. So, in 1961, John Cooper persuaded BMC to build a run of 1000 one-litre Minis to homologate them for competition use. The resultant Mini Cooper was a runaway success, with the fun factor turned up to 11 when the even hotter S version joined the range in 1963.

Like the attractive styling, which was simply a by-product of its engineering, the Mini’s legendary roadholding was a somewhat accidental consequence of its compact rubber cone suspension and wheel-at-each-corner layout. Early cars on crossplies aren’t quite as nimble, but the car’s ability to perform above its station is legendary. It’s no surprise the Mini enjoyed so much competition success, beating much bigger and more expensive cars – something it’s still doing in historic motorsport.

Over the years we saw the loss of the Cooper, the birth and demise of the slab-fronted Clubman range, a period of ‘stickers and trim’ special editions during the 1980s and the rebirth of the Cooper name in 1990. When the last classic Mini rolled out of Longbridge in October 2000, almost 5.4m had been built.

Nowadays, the Mini is firmly established as a global icon. What it isn’t anymore, however, is cheap. It’s now routine to pay £3000 for a project, while a decent 1960s Cooper S can make £50,000. Even the once-maligned 1275 GT can attract £20,000 or more, and a good Mk1 850 around £12,000-£15,000. Bits are still cheap, but the days of £500 runners are long gone.

Fiat 500

Smaller than the Topolino and 600 models that preceded it, the 500 is largely recognised as the genesis of the proper city car, but just as with the Mini, the public reaction following its launch in July 1957 was less than spectacular. As well as being overshadowed by the success of the 600, it was hamstrung by being an incredibly basic two-seater.

However, Fiat quickly improved it without upping the price. It added rear seats and extra chrome, while the door windows – previously fixed save for the quarter glass, were given a proper opening mechanism. Mechanical tweaks also boosted power from just 13bhp to 15bhp.

The 500 Sport introduced in mid-1958 saw an even bigger boost, with the enlarged 499.5cc motor good for 21.5bhp. What’s more, the ‘Cinquecento’ had been noticed by a certain Carlo Abarth – a relationship that began with an Abarth-tuned 500 breaking six speed records at Monza in 1958 and would go on to see hundreds of race victories. There were other hot versions too, such as Steyr Puch 500 from Austria.

The Nuova 500 was replaced by the D model in 1960, which brought in a 18bhp version of the 499cc motor. The subsequent F model of 1965 then saw the original ‘suicide’ doors replaced by front-hinged items, but it was the 500L of late 1968 that ushered in the biggest changes. Sold alongside the F model until 1973, it was mechanically identical but featured external nudge bars, plusher trim and a trapezoid instrument binnacle rather than the basic round one.

The final incarnation was the 500R, which dialled down the L’s equipment but got the same 594cc motor fitted to the 500’s boxier Fiat 126 replacement – although still without a full synchromesh gearbox. By 1973 the R had become the sole remaining 500 saloon model, running alongside the 126 until the final car was produced in 1975. With total sales of around 4m, there was no doubting the 500’s success.

Like the Mini, the 500 has long enjoyed iconic status. They’re a hoot to drive, with that little air-cooled twin wailing away in the back as it encourages you to wring every last bit of performance out of it. And though the positive camber at rear and skinny tyres seem frightening on paper, they’re perfectly commensurate with the car’s power output.

The same goes for the drum brakes, too – here’s a car that allows you to give ten tenths without breaking the speed limit, grinning from ear-to-ear as you do so.

But there are limitations. What seems joyous and characterful in the centre of Florence isn’t quite so fun on a hilly motorway in the rain. What’s more, with the engine leaping about all over the place, a refined experience it is not.

In contrast to the Mini, 500 prices have remained quite static in recent years. Around £3000-£4000 will get you a project, with runners between £5500 and £9000. Good cars can exceed £12,000 and exceptional examples, especially the earlier models, can pass £20,000. Abarth models, meanwhile, are on a par with Cooper S prices. Note that many cars will be left-hand-drive, but it barely matters given their tiny size. Engine transplants from the later 126 are also common.

Verdict

In some ways, the 500 and Mini stand on an equal footing. Both like to rust heavily, but both have a massive specialist and enthusiast backing, meaning there are very few examples that can’t be revived. They’re also similarly valued and can both be uprated courtesy of a thriving aftermarket.

As a city car making short trips and buzzing around, the Fiat 500 still works brilliantly. However, the Mini redefined what a city car was capable of. It might not look as chic as the little Italian, but it can do all the things the 500 can do with a useful injection of interior space, better handling, more power, greater refinement and a bigger tuning potential.

In mitigation, the intentions for the Fiat 500 were more modest in the first place, and it was around 20-25 per cent cheaper than the Mini, which itself was not exactly a money maker. You’d have to have a heart of stone not to like the 500, but in truth it’s much closer in spirit to a microcar than the more versatile Mini is. Whether the Issigonis car would have been as good as it was without the 600 and 500 to draw experience from, we can only speculate.

I’d like to think my dream garage would feature both cars, but if pushed I’d have to pick the Mini. I wouldn’t want to do without the Italian styling though, so the ideal solution would have to be an Innocenti Mini built under licence in Milan. Not the boxy De Tomaso one you understand, but the earlier Issigonis design enhanced with subtle Italian flair. For me that’s where both worlds collide, and wonderfully so.