What is it about those iconic models that appeals so much and drives lofty values? We break it down to the mechanicals and sneak in some extra doors, to see if you can have your saloon and race it too.

The sleek bodywork propelled through idyllic geography at a rate of knots by an engine – oh what an engine – that burbles, fizzes, sings, wails and inspires the drama that you felt missing until this very moment. It’s what many spend their tens, hundreds, multiples of thousands of pounds on – curved metal and mechanical marvel. Almost every exotic, super, iconic car is made by its engine – the beating heart, the metaphors never end – but what if you don’t have an open-ended chequing account? Are you destined to be without? We don’t think so.

BMW E3 vs E9

For all the visual spectacle and exclamations of Batmobile that the BMW 3.0CSL generates at car shows, it will really struggle to prove its £100,000+ price tag once leaving. It remains a seriously quick car, a lovely looking thing too, but for £70,000 less you can add a couple of doors and enjoy all but 5% of the racing-legend’s performance.

In fact, you add more than just doors. As a homologation special, the CSL’s purpose was less as a road car than a facilitator of motorsports and was set up appropriately; luxuries thrown out, ultimate performance pursued. Various bits of trim were discarded and thinner steel was used where possible, alongside new doors, boot lid, and bonnet made of aluminium alloy. Concessionaries in the UK decided to keep the sound proofing and glass windows that cars on the continent did without, thinking that we’d perhaps rather some refinement over extra mechanical noise and race-car-like Perspex windows.

Since we’re adding refinements, why not go the whole way? The so-called ‘City Package’ that UK cars were all fitted with added a good 134kg, bringing CSL’s weight up to 1300kg. This is actually heavier than the more humdrum, care not for aluminium alloy doors or low rooflines 2500 E3 saloon, and these are available today on the budget side of £10,000 – quite the difference to the CSL. But if the simple fundamentals of the New-Six generation’s drive – balanced handling, sharp responses, and excellent rolling refinement – aren’t enough and you want CSL-like performance, then the range-topping 3.0S, 3.0Si and later 3.3Li models are the ones to consider.

Those later 3.3Li models don’t add much beyond torque (up 12ft.lb to 213ft.lb from the 3.0Si), badge arrogance and an inflated price, so the top sporting choice is the shorter-wheelbase 3.0Si. Capable of pushing over 130mph, passing its carburetted 3.0S predecessor at 127mph, it is hot on the heels of the CSL. With the larger engine, it does weigh in at 1440kg and, along with slightly less tyre, drops an nth degree in the corners. However, the 3.0S and Si were upgraded to better handle the extra performance, with revised front geometry adding more negative camber and four-wheel vented disc brakes. The effect was successful enough to remove the need for the self-levelling suspension of the 2800, and produced a truly rapid sports saloon with neutral, balanced handling.

Arguably the levels of performance available in this format are all the more impressive considering the car’s ability to waft four passengers around in comfort. The 100mph+ image thundering down upon lesser motorway cruisers is barely different to the coupe, but there is a big difference for the bank account. While the E9 coupes, designated CS, can easily take £40,000 and CSLs more than double this, even top 3 litre E3 saloons hardly go for much above £20,000, with the very best struggling for £30,000 – the beginning of the coupe market. Why spend more for less? Or at least spend more for more, if only you could find an Alpina B2-S E3.

Jaguar XJ vs E-Type

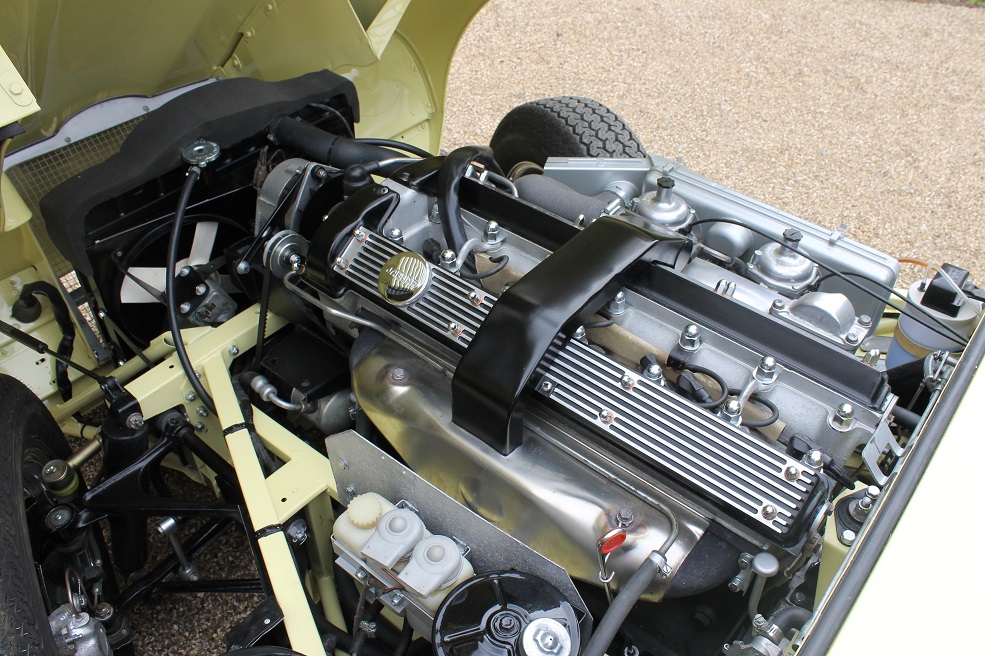

The E-type had the two key ingredients of a sports car perfected: gorgeous bodywork and a fine engine. It helped that Jaguar was skilled in setting up ride & handling compromises better than most, and so the E-type quickly gained status as the finest British sports car available, perhaps the world over. It even did remarkably well in the US market, where so many other British cars fell flat.

First equipped with the same XK6 engine in 3.8 litre form, it was bored out to 4.2 for the 1964 model, increasing torque by 43lb.ft to 280ft.lb. Power remained the same 265bhp and so did the E-type’s 150mph top speed. In 1971, the 5.3 litre V12 replaced the XK6 engines in the new Series 3 model, endowing the Jaguar with the mystique of 12-cylinders if not much extra performance. Today, it’s the early cars with the straight-sixes that have the most interest and lofty values, but even the later V12 models are still around the £50,000 mark – there’s no denying the value of that bodywork.

But if we put that bodywork aside for a moment, and simply look to how to access some of Jaguar’s finest chassis work and high-performance engines, the E-type begins to look excessive. The XK6 4.2 engine also saw duty in the Series 1 XJ, the car that ultimately replaced the famously fast Jaguar Mark 2 3.8, albeit with only two rather than the E-type’s three SU HD8 carburettors. XJ 4.2 power was therefore lower by 20bhp, at 245bhp, but the E-type-matched torque was delivered 250rpm lower down the rev-range. Trouble is, a 4.2 powering a fixed head coupe E-type only has 1315kg to shift, whereas the carb-down XJ installation is surrounded by nearly half a tonne more Jaguar.

Performance, then, is hardly comparable. However, the XJ isn’t without talent. It may lose around 3 seconds to the E-type on the way to 60mph, and another 6 to 100mph, but once up there its weight disadvantage is less telling, so composed and balanced is the chassis. The XJ also had in-board rear brakes, a feature shared with the E-type and continued in the XJ series until the XJ40 in 1986. The 4.2 XK6 continued its service for even longer, but it was the V12 that most appropriately brought E-type performance to the XJ.

With the 5.3 fitted it was a truly fast car by any standards, cracking 150mph if given the space. It may not look like an E-type, but there is a feeling to a fast Jaguar that transcends the sports car to sports saloon genres. Thanks to Jaguar’s work on the dynamics of the XJ, providing precise steering, near-infallible responses, and well-judged balance, the spirit of this fine British sports car is alive and well within its relative’s four doors. To afford this spirit is far more achievable too, since Series Jaguars are readily available for between £2000-£15,000, including the V12s.

Triumph TR6 vs Big Triumph

As the 1960s drew to a close, so was an era of British motoring. Standard was gone, absorbed into Triumph, and the TR6 found itself increasingly lonely in the medium-weight British sports car market. A final gasp of the Standard-Triumph six was provided by Lucas mechanical fuel injection, even if it ultimately proved nearly as unreliable as the British Leyland corporate structure. So equipped, the TR6 was not only given a healthy performance boost but also a velvety smooth character that had been hiding within the aged six-cylinder. The aggressive cams of the TR6 couple well with the more responsive, free-revving nature of the fuel injected engine, and finish that amplified Triumph-six howl with an enthusiastic zing at the top end.

This was the finishing touch for the sports car that had always been strong on its brutish torque and approachable handling. Fuel injected or not, the TR6 is a desirable car today and commands a range of five-figure prices for those interested. Priced between a GT6 and Stag when new, clearly the TR6 has exceeded its contemporary marketing shackles. So too has it soared past its saloon sibling – the Triumph 2.5PI – which was a good £200 more expensive at the time.

Outright performance is unsurprisingly ceded by the big Triumph saloon to the TR6, owing to a small weight disadvantage and more conservative camshaft profile. Total engine output is down by about 10bhp, but peak torque is delivered 1500rpm earlier at 2000rpm. With gear ratios very similar to the TR6, this gives the saloon a more relaxed gait but still quite impressive performance. It only gives up acceleration in seconds to its sportier relative as they approach 60mph, the gap opening further beyond 90mph where the saloon starts to plateau towards 110mph, while the TR6 charges onto 120mph.

When Triumph quietly phased out the troublesome fuel injection – and some continue to convert their cars to carburettors today – the highest performance option for both cars was the twin carburettor 2.5-litre six, designated 2500 for the saloon. In this specification it made 106bhp, 139ft.lb of torque, both representing a reduction of about 20% on the fuel injected arrangement. This compromises the big-Triumph’s ability to quietly cruise at 100mph; retaining the tall gearing shared with the TR6 presents more of a challenge to comfortably hold such speed at 4000rpm. But what it doesn’t lose is the silky delivery of torque and that distinctive Triumph-six howl under load, just as you would in the finest example of a high-output TR6, if not quite as clearly.

Except you’ll have spent something like £10,000 less. Mk2 Triumph 2000, 2500, even relatively rare 2.5PI models are available in the region of £2000-£8000, while the lower-volume Mk1 cars are still a way off competing with the lower reaches of the TR6 market. As a value prospect then, the big-Triumph with the big-six is a remarkably affordable way into a genre of sporting British cars that has since been elusive from the modern market. The rarer Mk1 2.5PI was perhaps the better controlled car in terms of handling, but any model – even the lowly 2000 can provide proper charm for the money. Against the savings from the TR6, any of the Triumph sports saloon range could be brought up to BMW 2500 level – as it was considered a budget rival at the time – with the popular fitting of polyurethane bushes or even retrofitting the optional power-steering.

For some though, the magic of the TR6’s more focussed setup and sporty shape will have undeniable appeal. The extra pace and spark of character of the sports car are things that here can’t quite be matched by the saloon, even if by class standards the big-Triumph, particularly the PI, is a strong package.