It took a long time for Standard-Triumph to successfully break into the post-war sports car market, but the Triumph TR2 was worth the wait. Here’s how to buy one today

Words: Rod Ker

Triumph’s post-war range had rather inauspicious beginnings. In 1945, when the Standard Motor Co took over the remains of Triumph, John Black, its uncompromising boss, decided that the recovering world needed a sporty car that would tempt Americans to hand over their precious dollars. ‘Export or die’ was the government’s mantra, applicable to British industry in general, and especially the automotive division. There were no military orders to fulfil, so the huge unused factories dotted around the Midlands would be making cars.

MG had been doing exactly that when the War Department handed back control after the Second World War, having launched the somewhat quaint TC within weeks of the end of hostilities. This was possible because the TC was essentially a 1930s car, wooden frame and all. Even then, steel unitary construction – as per the Morris Minor – had been recognised as the future.

Meanwhile, Standard had a couple of designs taking shape, its sporty model being known simply as the Roadster. Like the MG it had a distinctly old fashioned air, and relied on obsolete mechanical parts. Initially, power came from the 1800cc four-cylinder unit previously supplied to SS (Jaguar), but after a year that was supplanted by the all-new wet-liner engine most often seen in Massey Ferguson tractors.

Or, at least, it was a close relation of the ‘Little Grey Fergie’ power unit. Chicken-and-egg arguments continue about which came first, but it seems that the two were developed simultaneously, then followed different paths (the tractor version was actually a ‘monocoque’, as reinvented by F1 and not to be confused with unitary construction) and ended up on different production lines. As it happened, there was far more need for tractors than cars in the post-war climate; this was reflected in sales figures over the next decade or so.

The Roadster was put out to grass in 1949 with around 4500 made. Not a huge success, but expectations were modest. Sir John Black once again requested that his minions would construct a proper sports car. The goalposts had been moved by then, leaving a clear gap in the market between the new Jaguar XK120 and MG TD. There were others as we moved into the ‘50s, including the Austin Healey, of course, as created by a former Triumph luminary in conjunction with Len Lord of BMC.

As an aside, evidence that Sir John was less of a tyrant than imagined arrived in 1949 when he agreed to supply the new wet liner engine to Morgan, despite – or because of – his attempt to buy the Malvern company being rejected.

Things became complicated after that, when three part-complete TRX prototypes materialised, although it’s said that Black denied any knowledge of at least one! Moving swiftly on, the succeeding 20TS ‘2litre Sports’, (often referred to as TR1) took shape, borrowing suitable parts from the Mayflower saloon, including the front suspension and brakes. Time and money were in short supply, but somehow the new sportster was finished by 1952 and made its debut at the Earls Court Motor show in October.

‘Finished’ apparently isn’t the right word, as was discovered when the prototype was inspected and driven by the Press a few weeks later. The styling was typical of post-war Triumphs designed by Walter Belgrove, which all came with a dollop of Marmite, but beauty is in the eye of the beholder. The wet-liner engine had already proved itself, and could soon be persuaded to produce more than the initial 75bhp. On the minus side, the handling was reported as dreadful, demonstrating that a bodged and weak pre-war chassis just wasn’t fit for a 100mph roadster. As things stood, perhaps the limited power available was a blessing!

Back to the drawing board went Triumph, with help from newly-employed race and development ace, Ken Richardson. The would-be Triumph TR2 was extensively modified, both on the surface (e.g. lengthened tail) and underneath, where the ladder chassis was much stronger. Virtually the same hefty chunk of welded steel lasted until 1961, when the Michelotti styled TR4 arrived, complete with avant-garde wind-up windows. These are outside the scope of this guide, but briefly, 1965 gave us the TR4A with its more complicated Independent Rear Suspension, followed by the six cylinder TR5/250/6 models, which survived until 1975, when the totally new Triumph TR7 wedge materialised.

Body & Chassis

In the early classic era, circa 1980, it was commonly assumed that TR chassis were virtually immortal and usually required minimal repairs even when the external body panels were flapping in the breeze. Not so. But 30 to 40 years later the situation has changed again, as most Triumph TR2 examples have been restored at least once, and it’s highly likely that some of the main box sections will be touched by the tin worm.

The possible exceptions are genuine ‘dry state’ export models. You might have to suffer sun damage and the steering wheel on the wrong side (although that can be changed, at a price), but any car that spent its early life in southern California is likely to be worlds better than one that stayed in the vicinity of Coventry for a quarter century. Having said that, there are plenty of American states that have worse weather than soggy Britain, so make sure you know what you’re looking at, backed up by paper history.

The best way to inspect a car (not when wet) is to circle it gradually, noting how the panels fit, or don’t. Ripples are bad news, and on any convertible the doors give the game away as the body sags through weakening by rust. Then open the bonnet to look for signs of damage and peer into the spare wheel slot (which was intended to house a 5.50-15 crossply, modern 165-15 radials are a tight fit). Athletic types will be able to lie on the ground with a torch and see what might be afoot. Tapping with a blunt instrument will identify corrosion.

Then inspect the commission number plate, Triumph’s quaint version of a VIN, which shows coded information relating to the original attached vehicle (eg. ‘O’ for overdrive, ‘L’ for LHD), but doesn’t include a chassis number. It should tally with the car’s apparent credentials, but in a way that doesn’t mean much. Anyone can rivet an alloy plate to a bulkhead, after all!

It’s fortunate that Triumph ditched the ancient pre-war chassis used in the prototype, because it would almost certainly have rotted away and distorted in a few years. Instead, the production Triumph TR2 was based on thick steel main rails, aided by round cross-tubes at the rear, with extra bracing from a cruciform section brace in the centre. The sills in particular were part of the strengthening structure, not just cosmetic, and six pairs of engine/body/suspension mountings were welded along the rails. Again, it was never the case that a TR was roadworthy so long as the main rails were solid. It’s all structural really, and can’t be ignored!

The slightly better news is that engine oil leaks accidentally preserve the front chassis. Alas, the differential and lever-arm dampers couldn’t muster enough leaked lube to do the same at the back, where spring shackles could part company with rotten brackets. Both ends of the Triumph TR2, with its minimalist attitude to bumpers, were vulnerable to accident damage and misalignment, which didn’t help the handling, as one can imagine.

If that sounds bad, think what it’s like when the bracket spot welds start to split apart and the entire front end begins to break free, which can happen. MoT testers would have spotted potential disasters like this until recently, but 60 year old sidescreen TRs are exempt now. Still, while we can point out potential problem areas, putting a car on a proper ramp and viewing things from below will likely reveal plenty more. Some of this could be serious, and might explain why the car is for sale, and its price. While there may be no obligation for 40 year-olds now, a car with no MoT might raise suspicion. If you were selling an expensive Triumph TR2, surely it makes sense to spend about £50 on a test first? It might make thousands of pounds of difference.

On a general note, prospective buyers of alleged cheap or bargain restoration projects should be wary – at some stage the decision will have to be made about whether separating the body and chassis will be necessary. Obviously this is a major commitment, requiring hundreds of person-hours, a large workshop, plenty of expensive kit and some friends who like weight lifting.

There are different approaches: either brace the tub using angle-iron, or cut it in half. Either way there’s a chance the body and chassis will go floppy and never the twain will meet again – especially if they’ve been sandblasted, which will zap away metal as well as rust. Luckily, specialists like Revington can supply or recondition a chassis made on a jig, which effectively becomes your jig to build the rest of the car. Alternatively, it is possible to buy a bodyshell, but it would be naïve to expect it to drop onto the chassis and bolt down in a trice. Things didn’t work like that in the 1950s.

Either way, the expense is huge, even if you value your own time at £0 per hour. Sadly, plenty of home rebuilds stall after the initial gung-ho stage, hopefully to be rescued by professionals, maybe those TV miracle workers who can apparently turn a rusty hulk into a gleaming classic in a couple of weeks. If all this scares you off DIY restorations, then good, because it’s quite possible to spend tens of thousands on a ground up rebuild, then end up with a car worth less. OK, you won’t get the same job satisfaction or sense of achievement, but the smart money ends up with those who let someone else pay for the work

Engine and transmission

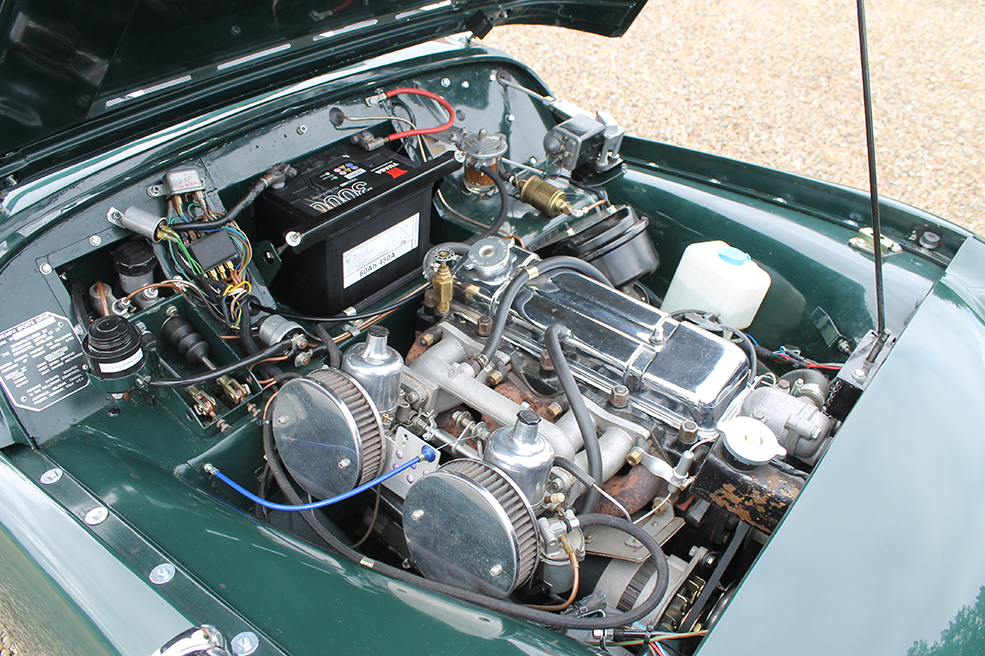

Contrary to lore, you can’t swap a broken Triumph TR2 engine for one found in an unsuspecting Massey Ferguson, but a dud motor is less of a problem than a rotten body. Not much happened to the wet liner four between 1953 and 1961. The Triumph TR2 began with 1991cc and 90bhp, fed by twin 1.5in SU s. Continuing with the ‘low port’ head, a bigger 1.75in pair of carbs boosted later TR3s to 95bhp. Updated 3s gained a new type of ‘Le Mans’ head, while the ‘high port’ version gave 100bhp. Finally, a 2138cc unit developed for the TR4 was available to order.

All the engines were renowned for their frugality (71mpg in Mobil Economy run), reliability and longevity. Said to be inspired by Citroen’s pre-war wet liner four as seen in the Traction Avant, 100,000 miles without major attention was common. Whether this was a direct result of the wet liner configuration, or just due to sound engineering generally, we will never know. In its day, the stroke was quite short for a displacement of around two litres, but TRs were more about low revs torque than power, which peaked at under 5000rpm.

However, it became apparent that the four could be tuned to yield about 30% more horses without exploding (the engine, not the horses). Standard fans will know that the same treatment from Ian Kellett Racing even turned the Vanguard into an unlikely track car, as seen at Goodwood, Silverstone and elsewhere.

On a more prosaic level, oil leaks are not unknown, particularly from the rear crank seal and timing cover area, which on the bright side kept rust at bay, as already described. Wet liner engines can also leak water internally and externally. Excessive pressure in the crankcases is not a good omen. On the practical side, the possibility of replacing the liners rather than reboring cylinders in blocks was/is a boon. You could save even more time and cash by turning the liners to present a less worn side to the piston!

The four-speed transmission is equally tough, if not refined. Early models lacked synchro on first, causing occasional teeth gnashing. Overdrive makes a TR a relaxed cruiser – still a noisy one, but some of that could be down to a single box exhaust. The later twin-box system will reduce ear bleeding. Incidentally, the exhaust went through the chassis, giving about 6in of ground clearance. That’s around 5in more than an Austin Healey…

Steering, suspension and brakes

Nothing fancy here. The rear end was a simple live axle with very little travel, controlled by lever-arm dampers, while the front was a compact double-wishbone affair with coil springs and telescopics. The latter was similar to the later Herald family cars and suffered the same ills – failure to lubricate the bottom trunnion could result in the threaded upright shearing off. Fortunately, it happens mostly at low speed when locked over. It’s a mystery why Triumph recommended grease for the TR, but only gear oil for the Herald.

Sidescreen TRs were handicapped by a vague cam and peg steering set-up, operated by a massive 17in Bluemel tiller. A rack and pinion conversion can transform the handling, as the steering geometry is improved.

The Triumph TR2 was noteworthy for being the first British production car to have disc brakes as standard. Contrary to rumour, it wasn’t the first in the world to use discs; that accolade went to Chrysler, although a 1938 Miller racer apparently had both discs and 4WD. The Jaguar C-Type also beat Triumph to it, but that was hardly a car you could buy by normal means. In 1955, Citroen’s DS was another pathleader.

Some early development testing for Triumph took place at the 1955 Le Mans, where one works Triumph TR2 entered had Dunlop discs all round, the other car front Girling ‘bacon slicers’, with rear drums. A year later at Earls Court Sir John announced that the forthcoming TR3 would come with Girling front discs, which caused a stir.

As in the Jaguar XK world, functional improvements are accepted in TR circles, so disc brake upgrades are common. Using parts from later models is one way forward, but there are compatibility issues. The alternative is to bite the financial bullet and buy a complete conversion kit for around £1500. Going further, 4-pot calipers and rear discs are available.

Interior and electrics

Surprisingly, leather upholstery was initially optional, probably as part of the drive to give the Triumph TR2 a $2000 price tag. On the 1953 electrical side, there are very few wires connecting very few components through fuses that offered little circuit protection, but the dash was functional.

Evidence that drivers didn’t trust Lucas was provided by a starting handle that went through the radiator before hooking into the crank. Oil pressure should be 70psi plus

Triumph TR2: our verdict

Separate-chassis Triumph TRs were some of the first cars to receive the classic seal of approval. After years in the wilderness, the 1980s saw increasing interest in ye olde wind in the teeth British sports cars. Suddenly, it seemed that even tatty TRs were worth thousands rather than hundreds. Repatriation, mostly from the USA where the majority were originally sold, became big business, and an army of specialists sprang up.

Supply and demand ensured that virtually every part was available, for a reasonable price. Purists didn’t like it, but bolt-on fibreglass wings and bonnets were very cheap and performed their function, the snag being that they couldn’t be attached to air or rust!

Today, the appeal of the Triumph TR2 is still alive and well, but values are very robust. Still, we reckon it’s worth the investment if you want something a little rarer and more interesting than the usual classic fare.