The Ford 100E and 107E saloons saw the brand’s small car offering enter the modern age. Thanks to their simple design and relative affordability, each offers a practical and enjoyable classic car experience over 60 years on

The decade or so after World War Two was a hard time for Britain. Food rationing continued until 1954, resources in general were scarce and much of the population endured significant austerity. Given these conditions it is quite understandable that Ford continued to produce a small car until 1959 which had remained largely unchanged since the early 1930s. The 103E Popular looked and drove like ancient history, but it was for many the only affordable family car available.

However, the 1950s was also a decade of enormous optimism, which expressed itself in forward-looking design and style. This was the energy that in 1953 gave birth to the Ford 100E. To 21st-century eyes these two and four-door saloons can look cute and retro, but much about them was thoroughly modern.

The Ford 100E brought the future to the common man. It embraced monocoque construction, a three-box body style, hydraulic brakes, independent McPherson strut front suspension and 12-volt electrics. The real cutting-edge stuff of front-wheel drive, hatchback body and transverse-mounted engines wouldn’t be part of the Ford proposition until 1976’s Fiesta, but the Ford 100E represents a real turning point for the company.

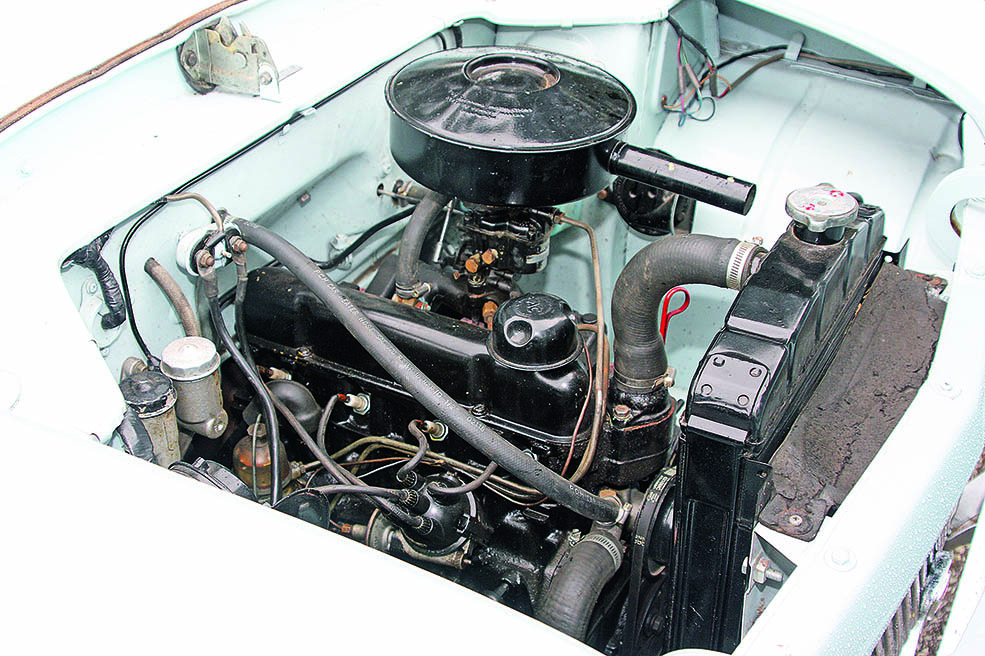

Behind the scenes there was less radical equipment. The engine was updated somewhat for the 100E, but it was still essentially the same venerable 1172cc, sidevalve, inline-four unit packed by the 103E. This was bolted to a three-speed gearbox, which even then was regarded as anachronistic. The rear axle was suspended on leaf springs like a brewer’s dray (though in fairness this was still reasonably common at the time), while wartime-era vacuum-powered windscreen wipers slowed or even stopped under acceleration.

On balance however, the Ford 100E was an excellent car – offering reasonable accommodation for a family and its luggage. It had light controls and – thanks largely to the independent front suspension – pleasantly neutral handling. The stone-age rear setup did tend to generate snap oversteer when driving the car hard in damp conditions but the engine’s 36bhp was hardly dangerous.

The two-door body was named Anglia while the four-door car bore the Prefect badge. While the basic cars were fairly spartan to keep the list price down, various optional extras could be specified. A De Luxe package also featured some of these, bringing luxuries such as a heater, a radio and extra body brightwork to the party.

Throughout its production life the Ford 100E sold well without evolving very much. In early 1955 the all-drum braking system acquired drums of increased diameter. A 1957 facelift brought revised front grille and lights, changes to the bumpers and a larger rear window. Mechanically, the engine and transmission remained the same throughout. However, in 1959 the 103E Popular was finally discontinued.

At this point the 100E model took on the Popular badge and became a two-door only model. The four-door car was revised to create the 107E Prefect, something of a hybrid with superficial restyling of the body, plus the new 997cc overhead-valve engine and four-speed transmission that would find a long-term home in the 105E Anglia. Most of the Ford 100E and 107E cars produced were saloons. However, the rare Escort and Squire-badged estate versions can occasionally be found. Even rarer are cars equipped with a semi-automatic gearbox or a Newton drive clutchless gearchange.

One man who knows more about these models than most is Mike Wood. The product of a Ford dealer apprenticeship, he and his business partner Chris Evans have run Old Ford Auto Services from its Bracknell, Berkshire base since 1989. The Ford 100E and 107E are at the core of the business, which started as a hobby but grew to become one of very few specialists in the model.

Bodywork

“You face the usual Ford stuff with these cars,” says Mike. “Rust, in a word.” The body is prone to severe oxidisation. Especially vulnerable points include the inner and outer sills, the dirt-collecting open section at the front end of the sill, the front suspension strut top mounts, the area around the leaf spring front mounts, the lower rear quarters and valance. “Almost every car will have had repairs,” Mike explains. “You need to assess the quality of this work.”

Fortunately, a wide range of repair panels is available. Mike describes the cars as “well catered-for. You can get lower rear quarters, for example,” he says. “On four-doors the wheelarch panel rots but you can replace the whole section.” He notes that the car’s design makes repair relatively feasible, as items such as the front wings, front panel and doors simply unbolt to give access.

Mike recommends paying particular attention to the floor. “The window rubbers leak,” he says, “which creates rot in the front footwells. Complete floor sections are one thing you can’t get as a repair panel. Patching this takes time and expertise.” As well as repair panels, much of the body trim is available nowadays. Some of the brightwork on later cars is stainless steel, so examples should look clean in this respect.

Mike emphasises the importance of looking hard at a car, especially if it is in clean condition. “Take a magnet,” he says. “A nice looker that has been given a quick make-over can be a basket case within a year.”

He recommends prospective owners to join an owners’ club, such as the Ford Sidevalve Owners’ Club. “People in clubs are incredibly helpful,” he explains. “One really good way of finding a decent car is through word of mouth within a club. You’ll also find friendly people happy to provide advice, and some of these guys really know their stuff.”

Engine

When it comes to the Ford 100E’s power, both the sidevalve and overhead-valve engines are simple and reasonably rugged units. Their main enemy is lack of maintenance in earlier years. “The sidevalve lasts well as long as it isn’t revved too much,” Mike says. “If it’s treated with respect and has plenty of oil changes it should be fine.” Strange noises and blue smoke when running are obvious warning signs of wear to valve gear and bores. Excessive bore wear due to the deterioration of piston rings requires a rebore and new pistons, so a receipt for this job is actually an encouraging sign.

It isn’t unusual to find the engine bay occupied by a non-standard unit. These cars have long been the subjects of modification. “Favourite swaps used to be the Crossflow and Pinto,” Mike says, “but lots of people are converting them with Zetec and Duratec now.” There is nothing wrong with a converted car, but both the engine itself and the quality of the installation need to be looked at carefully. “It also needs upgrades to the steering, brakes and suspension,” says Mike. “All of this work needs to be checked over.”

Thanks to the popularity of upgrades, original engines are easy to source at very affordable prices. Keeping a standard example on the road shouldn’t cost the earth.

Transmission

The three-speed gearbox in the Ford 100E has no synchromesh on first gear, which can seem awkward at first for drivers used to modern cars, but the gearbox itself is a reasonably durable unit. A test drive is required to check for noise from the gearbox. Poor synchromesh on second gear is a common fault, and if an example jumps out of second, then work will be required.

The differential is also prone to wear, but can run noisily for a long time without failing. Mike recommends that any new owner changes the transmission oil as a precaution. “Spares are available,” he notes encouragingly. “Also, upgrading the ‘box to the four-speed from a 105E Anglia has always been popular, so it’s easy to find a three-speed and they don’t cost much.”

Suspension, steering and brakes

Thanks to its simplicity, the suspension in the Ford 100E is unproblematic. So even if an example has elderly bushes and worn front strut inserts, it can be repaired without undue effort or expense. “It’s all straightforward,” Mike explains. “All the spares are available on the internet and eBay.” Companies such as Small Ford Spares stock these, too. The rear leaf springs can sag with age, but can be re-tempered if new items prove difficult to find.

Even in perfect condition, no car with worm and peg steering will feel as direct as a modern rack and pinion setup. While many of these cars have been converted to such a system, those with the original mechanism need to be checked carefully. Fluid leakage from the steering box is a bad sign, although the seal can be replaced to cure this.

However, if the car wanders with the wheel in a straight-ahead position, then the roller peg could be worn. This is no longer available, and could cause a headache-inducing search for a replacement box. A Ford 100E or 107E should have light, pleasantly direct steering considering the old-school nature of the system, with less than two turns of the wheel lock to lock.

The all-drum brake system, when functioning well, actually does a reasonable job of stopping these cars. Pre-1955 examples originally had seven-inch diameter drums, which proved prone to fade with prolonged use. A move to an eight-inch system cured that problem. Slight changes were made in 1957 to improve things further. Any 100E or 107E should pull up reasonably well, and in a straight line. Veering to one side indicates a seized mechanism.

The main enemy to the brakes, Mike says, is the classic status of the cars. “Check the fluid,” he warns. “If it’s black, that means it is full of rubber. The fluid eats the seals over time, especially in cars that are only used occasionally. Any unrestored car should get a new set of rubbers and fresh fluid. We put silicone brake fluid in. It’s more expensive, but it lasts longer and cures the problem.”

Long-term, a car with the larger brakes will not only stop better but be easier to maintain. “One thing that is rare now is the early wheel cylinders,” Mike says. “The later ones are the same as for the 105E, so they’re cheap and easy to get.”

Originally equipped with cross-ply tyres, most cars will now wear radials. These are not only cheaper, but also provide significant improvements to the handling.

Interior and electrics

Although changes were made to the Ford 100E and 107E cabins throughout their production life, all these cars have a pleasingly simple and robust interior. It is a symphony of painted metal, chrome trim and vinyl – although some cars may have leather seats thanks to Ford’s options list. It isn’t a disaster if an otherwise sound car has sagging or worn seats or vinyl panels, as all the soft trim is readily available. “Companies like Aldridge Trimming make factory-fresh trim pieces and seat covers in all the colours”, Mike recommends.

The car may or may not feature a heater. It was largely an option on the 100E and standard on the 107E, although Mike warns that these are different units. If there is one it should work well, but check for fluid leaks as – like worn window rubbers – these can cause corrosion to the floorpan.

The 1960s was a boom time for aftermarket automotive gadget sales, so any old Ford may feature holes in its dash where auxiliary dials, switches, map lights and radios once resided. These should be viewed with caution unless you are contemplating a strip-down of the car, as interior metalwork can prove remarkably troublesome to repair. Mike also recommends a good look behind the dash. “People used to add equipment and do their own electrics,” he says. “It’s worth checking that there’s not a rat’s nest of old wiring back there, which has ‘fire hazard’ written all over it.”

Overall, Mike says, the electrical system of these cars is very simple and – in good condition – works well. Thanks to 12-volt power several pieces of equipment can be used at the same time, so the lights shouldn’t dim when you turn the radio on, for example. “But it’s also really old,” he notes. “Corroded terminals and bad earths are the usual causes of something not working properly, so it all needs checking over carefully.”

The fitment of windscreen wipers powered by inlet vacuum may have saved Ford a few pounds, but has undoubtedly endangered the lives of many 100E and 107E drivers over the last six decades. Any example will have weedy, fitful wiper operation at best, which deteriorates under acceleration. Complete non-operation is also possible – an indication that the vacuum motor has died or that pipes are leaking.

Happily, parts are available to fix the system. It is also possible to convert a British Leyland mechanism to fit the Ford, which provides reliable, two-speed wipers. If you’re lucky enough to find an example thus equipped, check carefully that it works well. The electrical components are notoriously unreliable and the linkage requires fettling to fit. Ensure that the wiper arms don’t tangle when moving.

Modification

Today, the appeal of the Ford 100E and 107E is twofold: primarily, they are relatively affordable in comparison to the later Mk1 and Mk2 Escort – values of which have headed for the stratosphere in recent years. Secondly – partly because their lower value means that they haven’t become sacred cows as some 1950s cars have – these machines are eminently modifiable. This has fostered a broad church of ownership from originality purists to drag racers.

Ford’s little piece of post-war history is, in every way, popular. A decent Ford 100E or 107E will provide very satisfying classic car ownership. These cars might be of pensionable age, but they are modern enough in design to be reliable, enjoyable and pleasant to drive.

Mike’s advice is simple: “Buy the best car you can afford,” he says. “It’s just as important if you’re going to modify it. I think the reason so many are for sale as unfinished projects is because people get bogged down in restoring a ropey car before they can even start with the fun stuff.”

Words: Phil White