The Traction Avant is the pre-war car that drives like a much newer machine, making it a tempting package today. Here’s how to buy a great one

The Traction Avant wasn’t the first front-wheel drive car, but by combining this with monocoque construction, it was a massive groundbreaker when launched in April 1934. With other features including an overhead-valve engine, all-round torsion bar suspension, hydraulic brakes even rack and pinion steering just two years after its launch. It was, quite simply, the world’s most advanced family car.

The Traction Avant’s revolutionary design brought financial implications, though, thanks to astronomical research and development costs. Citroën ended up a bankrupt company, only to be rescued from oblivion by Michelin – one of its biggest creditors. Sadly, Andre Citroën himself died six months later, seemingly crushed by his failure.

When evaluating, the most basic division is between the cars built in France and those built at Citroën’s plant in Slough. The latter had leather seats and a wooden dashboard, while customs rules led to the fit-ment of Lucas electrical parts and Girling brake components. Slough-built cars can easily be identified by the big chevrons of the Citroën logo being mounted behind the grille rather than in front of it. There is a further division, too: Traction aficionados prefer the pre-1952 small-boot (‘malle plate’) cars over the later big-boot (‘malle bombe’) versions, and this is reflected in the values.

By far the most common Traction Avant model is a four-door ‘four-light’ saloon with a 1.9-litre four-cylinder engine. In France this was designated an 11CV model, while in the UK it was rated at 15 ‘tax horsepower’ under our RAC system. Two main styles were offered, the ‘Legere’ (or Light 15 in the UK) and larger 11CV ‘Normale’ (or Big 15). There were the longer wheelbase Familiale and Commerciale models too, the latter with its opening tailgate, and in 1938 the 2866cc six-cylinder Six with its extra power and performance was also added. Most desirable of the lot, however, were the Light 15 Roadster and Coupe models, each one boasting sporty two-door lines.

The Traction Avant went from strength to strength, finally going out of production in 1957 to make more room for the equally revolutionary DS – a remarkable career interrupted only by the Second World War.

Bodywork

Slough-built cars have proven to be more rust-prone than French cars. British Tractions had the widely fitted option of a sliding metal sunroof, which is a good breeding ground for rust, even without the drain holes getting blocked and allowing water to collect and then drip into the cabin. Slough cars also had UK-type trafficator arms fitted in their B-pillars, which is another entry-point for water and damp. Note that on all Traction Avant models, the roof centre section is a separate panel to the rest of the structure, with a visible seam that makes it look like a blanked-off sunroof – this is not the case. Many restored cars will have had the seam lead-loaded and painted over, so this is a good ‘tell’ as to the originality of a car, or the fastidiousness of a restoration.

Most of the Traction’s structural strength is in its sills, which are hefty three-part items (inner and outer, with ribs in between) and the floor, which is corrugated. Check all along the sill on both sides as thoroughly as you can and be aware that any visible rust on the outer sill almost certainly means there is worse corrosion inside. Look for signs of the doors scraping on the sills or binding on the latches, which might mean that the body has deformed due to rust, even if it has been patched and repaired. Inspect the area around the rear of the sill and the base of the C-pillar, as this is where the rear suspension attaches to the body. At the other end of the car, check the door and bonnet shut lines and inspect the A-pillar and bulkhead for signs of deformation, which would indicate that the body has lost its strength and is bending under the weight of the drivetrain.

Also look at the body extensions that run beneath the bonnet and behind the front wings (these are called the ‘jambonneaux’) for signs of damage caused either by corrosion or accidents. Lifting the bonnet(s) lets you see the engine-bay side of the bulkhead and the front subframe mounts. The back tip of the front wings have an overlapping seam where the two skins of the wing are wrapped around each other, another breeding ground for rust. Many Tractions have kick-plates or mudflaps fitted here, which can hide eaten-way metal.

The front floor pan can also rust out, compromising the monocoque. This is often due to the aforementioned sunroof drains on Slough cars and/or perished seal on the cabin vent flap in the scuttle panel. The boot floor rusts out if the boot seal perishes and/or the drain holes become blocked. Check the lower parts of the door skins and frames. The bonnets, front and rear wings, boot lid and doors are all bolt-on items on the Traction. Repair sections for common rust areas are easily available. New wings are very expensive and have been for some time, so you may see cars with glassfibre reproductions.

Engine and transmission

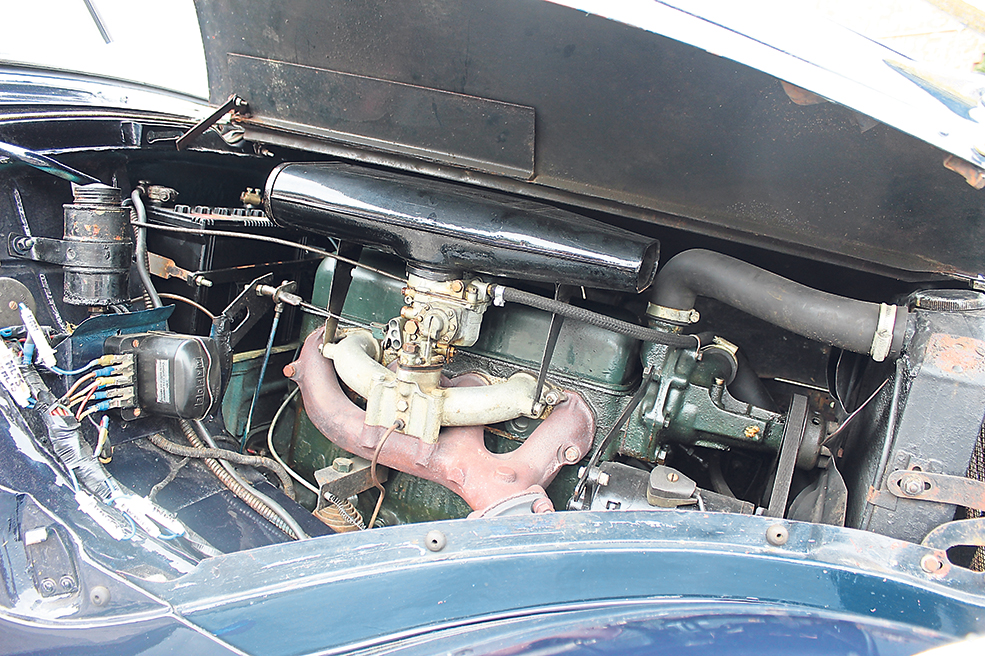

The Traction Avant’s engine is sturdy and suffers only generic wear and tear, while the Traction Owners’ Club can provide Traction-specific bits. On all but the very last Tractions, the four-cylinder engines had old-fashioned white-metal bearings which are expensive to refurbish if worn, but many have been modernised with shell-type bearings from a late-model ‘11D’ engine. The 11D engine was also the only one to come with a proper oil filter – most Tractions rely on very frequent oil changes at 1500-mile intervals, so try and see evidence of this level of upkeep. No Traction had an oil pressure gauge or light as a standard fit either, so listen out for rumbling bearings or knocking big ends.

There was no timing chain tensioner, so some front-end rattle is normal. If it is excessive, replacement is an engine-out job since the engine sits ‘backwards’ in the engine bay. An aftermarket tensioner kit has been available for a few years and is a welcome addition. The four-cylinder engine is mounted on steel volute springs – if these get tired, the engine rocks excessively at idle and can cause clutch judder and a loud knocking on the bulkhead when on the move. Both new volute springs and kits to fit conventional rubber mounts are available.

The six-cylinder engine isn’t quite as tough as the four-pot, but is still far from troublesome. Neglect and age can cause head gasket problems or a warped cylinder head, so check for signs of the coolant and oil mixing or signs of weeping along the head/block join. The starter ring gear on the flywheel can work loose, giving a gnashing sound when starting, while a rattle from the rear of the engine bay can mean that the crankshaft damper is working loose, which can cause serious damage if it breaks up or comes adrift.

Gearbox problems are rare, other than worn-out synchromesh (only between top and second gear on all Tractions). If the car jumps out of gear when under way, this may mean the gearbox needs a rebuild (which is expensive) but it’s more likely to be that the clutch interlock – which latches the gear lever in position when the clutch is raised – needs adjustment, which is simple. Whines, knocks or shrieks from the gearbox mean that the bearings or the gears themselves are worn.

Listen for clacking sounds from worn drive shafts on full lock, and feel for binding driveshaft joints caused by seized or worn universal joints. Twist each part of each driveshaft in opposite directions to check for wear in the splines (also shown by lurching or knocking sounds when going on and off the power at low speeds in first gear). Check to see that the grease nipples for the driveshafts and joints look like they’ve been regularly attended to.

Suspension, steering and brakes

The Traction Avant’s suspension is beautifully simple, consisting of torsion bars all-round, with metallastic bushes and a telescopic damper on each corner. There is little to go wrong here other than simple wear and tear. The torsion bars themselves very rarely sag, so focus on the condition of the bushes – they are easily visible on full lock. If the buyer will let you, get the front end of the car off the ground and rock and wiggle the wheels to check for play in the bushes – otherwise shown by vague steering and knocking sounds from the suspension.

The rear bushes are harder to see, even with the rear end raised, but the audible and driving checks are the same. It’s quite possible to replace all the bushes, but it requires specialist equipment and is therefore expensive. The Owners’ Club loans special tools to members if you want to tackle this and other jobs yourself.

The steering on nearly all Tractions is rack and pinion and gives no trouble. The steering will always be quite weighty, but should be smooth and accurate, with virtually no play. Normale and the ultra-long wheelbase models were available with optional power-steering in the 1950s. This system gives little issue so long as the pipes and connections aren’t leaky, the pump doesn’t shriek or groan and there are no tight spots in the steering.

The brakes are drums on all corners, with hydraulic action but no servo. Just make the usual checks for leaky pipes, cylinders and reservoirs. A trial emergency stop should lock both the back wheels without any dragging to left or right.

Interior and electrics

Most French cars have a single Art Deco-style combined gauge unit, while Slough cars have individual circular dials. The latter are Smiths or British Jaeger items, and are easier and cheaper to repair or replace if there are any problems.

Trim kits for the seats (in leather or cloth), door cards, carpets and headlining are all available for more the common Traction models, although the kits themselves are expensive, as is getting an upholsterer to fit them. Check the headlining for signs of water leaks from the roof panel, especially on a car with a sunroof.

The British cars all have 12-volt electrical systems with Lucas components, which means parts can easily be found. French Tractions originally had 6-volt systems with Ducellier parts that are harder to find, especially this side of the Channel. As built, the Traction Avant doesn’t have a heater as such, relying on a duct carrying warm air from behind the radiator. Many, if not most, UK-based Tractions have been fitted with a proper heater of some sort, but bear in mind that an import may well not have one.

Citroën Traction Avant: our verdict

The Citroën Traction Avant is a much more useable and easy-to-live-with classic car than its 1930s styling would suggest. Easy to drive and mechanically simple, there’s nothing to stop a well-maintained example from serving as regular transport. Good parts supply, enthusiastic club support and undeniably attractive styling all count in the Traction’s favour. Rust can be an issue, but buy well and you’ll have a genuinely useful and thoroughly interesting classic on your hands.

There is a big variance values between the ‘standard-issue’ 1.9-litre saloon models and the much rarer other versions. ‘Big boot’ French-built 11CVs with left-hand drive can be found for four-figure sums, and a £12,000 budget should buy a very nice example. There is little difference in the values between otherwise equivalent Legere and Normale models, but post-1952 ‘big boot’ models are generally worth about 25 per cent less than an otherwise identical ‘small boot’ model. Slough-built Light/Big 15s are rarer and so decent examples start at the £15,000 mark and go up to around £25,000 or a little more for a really good one.

Six-cylinder cars, French- or British-built, start at around £30,000 for good examples and go up towards £50,000 for the best, and this is the same sort of budget you’d need if you really want a decent long-wheelbase Familiale or Commerciale model. A two-door model in good nick can be £50,000-80,000 or even breaking into six figures for a genuine original cabriolet.

Citroën Traction Avant timeline

1934

Traction Avant launched as small-booted 1303cc model (badged ‘7CV A-C’ in France and ‘Light 12’ in Britain) with interior-accessed boot. 1303cc ‘7A’ model replaced by 1529cc ‘7B’ in June, identified by twin windscreen wipers. October 1934 sees 7B replaced by 1628cc ‘7C’. November sees 1911cc ‘11CV’ (‘Light 15’ in Britain) introduced, also available as wider and longer ‘Normale’, or ‘Big 15’. ‘Conduite Intérieure’ and ‘Familiale’ models also added.

1936

Painted front grille replaced chrome item, headlights restyled, opening bootlid introduced. Rack-and-pinion steering replaces worm and roller set-up in May

1938

15h model launched, sporting 2867cc straight-six (known as 15/6 in UK with a handful sold before the war). Hatchback Commerciale with a removable rear seat added to range (two-piece hatchback changed to one piece after the war)

1939

War breakout disrupts Traction Avant production, ultimately paused by 1941

1946

Traction production restarts, with increased pricing due to shortage of tyres. Roadster and Coupe models no longer built

1952

Big-boot (‘malle bombe’) versions launched

1954

2876cc six-cylinder 15/6H used as testbed for upcoming DS’ hydropneumatic suspension

1957

Traction production ends, with almost 760,000 cars made in total

Citroën Traction Avant alternatives

Citroën DS

Although the Traction is undeniably classy, significant and magnificent, its successor built on all the Avant’s assets and added a plethora of new innovations. The Citroën DS boasted timeless, beautiful styling, a modern interior and hydropneumatic suspension that granted it the best ride of any car in the world. Throw in numerous safety and engineering innovations, and you’ve what I consider the greatest car ever made.

Lancia Flavia

The Traction Avant was so far ahead of its time, you have to jump to the 1960s for a genuine rival from abroad. The Stylish Flavia offered Lancia charisma, strong performance and the option of coupe, convertible and the Zagato Sport variant. Today they’re rare, expensive and challenging to own, but absolutely worth it.