The Aston Martin DB7 is still a surprisingly affordable route into luxury British GT ownership. Here’s how to buy a great one

Words: Sam Skelton

The Aston Martin DB7 has a somewhat convoluted development history. It began with the Jaguar XJ41, a planned twin-turbo all-wheel-drive monster GT which would replace the XJS in the late 1980s. Once this project was scrapped under Ford on cost grounds, Jaguar still needed a solution – which was outsourced to TWR. Owner Tom Walkinshaw asked a young Ian Callum if he could transfer the styling of the XJ41 onto the existing XJS chassis in order to interest Jaguar with the end result. Jaguar management liked what it saw but wasn’t prepared to pay to buy the rights from Walkinshaw, instead poaching Callum, and setting him to work on the development of what became the XK8.

Meanwhile, Aston Martin – newly purchased by Ford – was looking to build an entry-level model. TWR, irked by Jaguar’s refusal to proceed, offered its XJR XX concept to Aston Martin as a ready-made proposition which could draw heavily on the Ford parts bin. The rest is history – subject to the replacement of the Jaguar oval grille with a suitably Aston shape and the introduction of Aston’s signature wing vents.

Those early cars didn’t just use a Jaguar design and floorpan, but also a Jaguar engine – the 3.2-litre AJ6 from the XJ40, supercharged in a similar manner to the parallel work being undertaken in Coventry for the X300 Jaguar XJR. This 3.2-litre engine developed 335bhp, enough for a 0-60 time of just 5.4 seconds. Inside and out, parts from the Ford bin were joined by new trimmings, and the result was one of the most effective parts-bin designs of all time.

Special editions such as the Stratstone LE and Alfred Dunhill may be more valuable owing to rarity, but the basic shape and trimming of the original are so right that Aston never really mucked about with them.

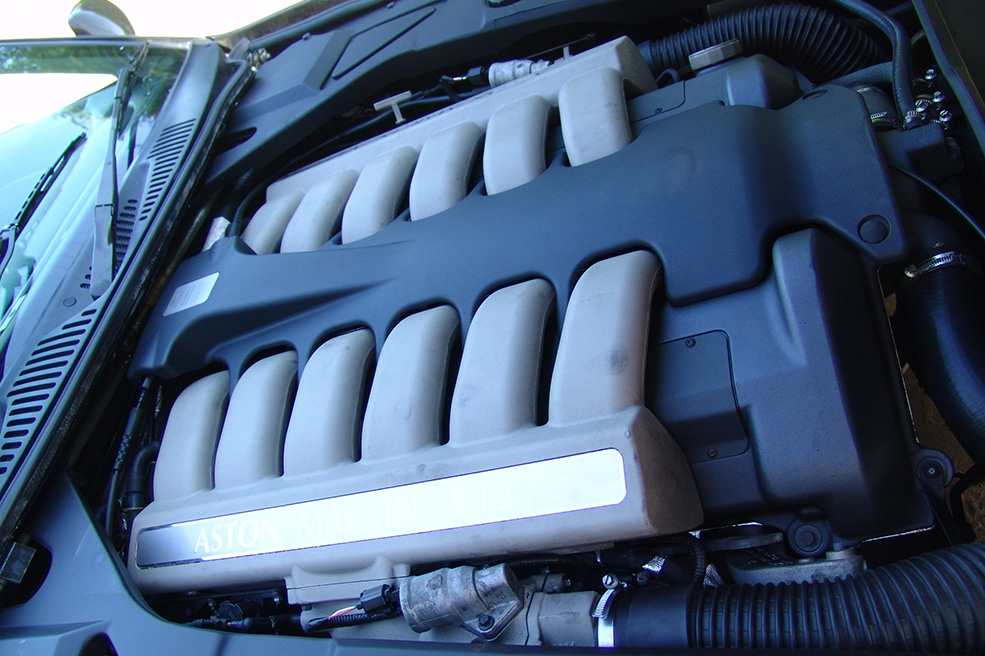

The DB7 family evolved, first with the Volante convertible of 1996 and then with the V12 models of 1999. These used a V12 developed from Ford’s Duratec V6 and can be identified from outside by large round indicator and driving lamp units in place of the svelte oval units of the six-cylinder car. The last-of-the-line cars were dubbed ‘GT’, with a ducktail spoiler and more power; these are now among the most valuable DB7s today. Finally, 99 Zagato-bodied DB7s were made in 2003, these cars now mostly in the hands of ardent Aston collectors.

Around 3000 six-cylinder and 4500 V12 models were built in total – by the end of production in 2003, one in every three Astons ever built was a DB7. That ubiquity has helped second-hand values for buyers – while we’ve left the days of the £13,000 DB7 behind, you can still find a decent coupe for under £20,000 – and those prices will only go one way.

Bodywork

Check the front bulkhead thoroughly, as like Jaguars of the same age there are water traps which can lead to corrosion. The double-skinned bulkhead is a structural element and corrosion here is bad news.

Likewise, check the jacking points, radius arm mountings, and the rear edge of the sill where it meets the wheelarch. These areas – along with the door bottoms and the wheelarches – are areas very prone to trapped moisture and corrosion from the inside out, so it’s a good idea to check thoroughly.

Suspension top mounts and the area behind the dampers are worth checking too – along with the base of the rear screen, which if left untreated can allow water ingress into the cabin and boot. Finally, check all the floorpans thoroughly as they’re widely known as a rot trap. Six-cylinder examples have better rustproofing than V12s, though the chassis legs will also need checking on Vantage models.

Finally, check thoroughly for crash damage. Check the panel gaps – these should be even, albeit not as even on the earliest cars as on later models. The wings, bootlid and bonnet were made from composite until 1997, when a steel bonnet was fitted. Any poor paintwork finishes on these panels are giveaways of a hasty respray.

Engine and transmission

Smooth, effortless power is a big part of the Aston Martin DB7 experience, so it’s important to make sure the engine is in fine fettle. Engine and gearbox oil coolers can leak on the six-cylinder engine. Timing chain tensioners can fail, so keep an ear open for rattling, or for ‘mooing’ upon start-up.

The Eaton supercharger is reliable if kept oiled, but the Works Prepared bigger intercoolers can fail leading to overheating. Supercharger belts should be renewed every 30,000 miles and a loss of power could mean it’s snapped. Exhaust manifolds can crack, and they’re replaceable – but bear in mind there are two, one for the front three cylinders and one for the back three.

Generally speaking though, the 3.2 is as reliable as the Jaguar AJ6 engine upon which it’s based, so you’re unlikely to have significant trouble if you buy a 3.2. An added bonus is that they can be serviced and maintained by Jaguar specialists, which tend to come cheaper than Aston Martin specialists for the same work.

The V12 is prone to collapsing coolant hoses and radiator thermostat failure. All need regular coolant changes as they’re all alloy engines, but bear in mind that a V12 requires OAT coolant. Don’t put glycol in, as the two will react and form a gunge which will clog the cooling system. Like the six-cylinder, the V12 is generally reliable, and specialists used to later DB9s and Vanquishes are capable of looking after the DB7 with ease.

Both the 3.2-litre and V12 models came with a choice of manual or automatic transmissions, though the likelihood is that you’ll end up with an automatic purely due to numbers built. The 3.2-litre Aston Martin DB7 uses – broadly speaking – the same gearboxes as used in the Jaguar X300 XJR. That means a Getrag 290 five-speed manual and a GM 4L80-E four-speed automatic. Both are hardy units in operation, though too many full-bore starts in the automatic could wreck the shift solenoids; it’s better to drive it like the GT it is. Parts are easily sourced to rebuild both units if you find yourself in difficulty.

The V12 models each gained a gear, with a Tremec T56 six-speed manual and a ZF 5HP30 automatic being used. The automatic was also used in the Bentley Arnage Green Label, while the manual was developed for the Dodge Viper – proof if it were needed that it’s hardy enough for the Aston Martin DB7. Again, neither unit should give serious trouble.

Suspension, steering and brakes

Uneven front tyre wear can be caused by incorrect steering geometry – it may just need tracking, but it could be a sign of accident damage. Wheels are prone to buckling too, especially the wider rears of the Vantage. Walk away from a six-cylinder with V12 wheels, as the change in offset affects the handling. Make sure they’re all on the right tyres – unidirectional tyres are what the car was designed for, ideally Bridgestones.

The Driving Dynamics package allowed owners to upgrade suspension, brakes, wheels and bodywork – or a mixture of parts. The suspension and braking components are desirable extras; the bodywork we’d leave to your personal taste.

Rear brake pads on the early cars are shared with the Jaguar X300, which can represent a saving. Sadly, the rest of the braking system is Aston’s own, with no clear savings to be made. Many owners in addition have fitted upgraded brakes over the years – if this has been done, ask to see receipts to be sure of exactly what you’ve got. Apart from that it’s a relatively simple system by 1990s standards – so just make sure the ABS works, make sure the brake lines are in good condition, and check for warped discs on the test drive.

Interior and trim

Walnut and leather are the order of the day inside the DB7. These can be retrimmed easily enough, should there be any damage – used seats are available but you’ll see a better result with an independent trimmer.

Unlike many bespoke cars, much of the interior is shared with other models. The internal door releases, for instance, are from the Mazda MX-5, the window switches are from the Ford Granada, steering wheel is from the Jaguar X300, and the instrument pack is a revamped XJS unit.

Air vents are shared within the Ford stable too but while to many this smacks of cheapness, the bonus for those of us considering an Aston Martin DB7 as a modern classic is that everything is available from a cheaper source.

That steering wheel, for instance, costs half as much with a Jaguar badge; the window switches can be found in every scrapyard, and there are plenty of Mazda specialists for other small bits of trim. Do your homework and shop around for the best bargains.

Make sure all the toys work – beware that cassettes will be stuck in the early radio in fifth gear, this is a design flaw and not a fault. Air con should blow cold, windows should be prompt and quiet, and while all faults can be fixed, the cost of doing so needs to be factored into the purchase cost of the car.

In the case of the air con this could well be an evaporator – a 21-hour job on the Vantage, and a slightly less ridiculous 12-hour job on a six-cylinder car.

Verdict

Who doesn’t secretly want to be able to say “I drive an Aston Martin”? It’s the best badge in the business. Granted, ubiquity is eroding its mystique but a classic Aston is still one of the coolest cars on the road. The six-cylinder cars are sensible enough to run thanks to their Jaguar heritage, and while the V12s are cheap to buy now they won’t always stay that way. Remember, this is the car that spearheaded Aston’s revolution into the marque it is today, and the chance to own something so pretty with that engine – for so little money – will never come around again.

It must be emphasised that the DB7 is not a car to buy blind, nor is it one to buy without specialist assistance. We would always recommend trying as many DB7s as you can before you make a purchase, and ideally enlisting a specialist to inspect a car before you buy. Our pick would be a 3.2 automatic coupe, and by lucky chance this happens to be the most affordable DB7 of the lot – all for the price of a new top-spec new Ford Focus.