The Triumph Stag is a cornerstone of the classic car hobby that’s popular for good reason. Here’s what you need to know

Words: Sam Skelton, Chris Randall Images: Gregory Owain

Launched in 1970, the Triumph Stag was a happy accident more than a deliberate piece of product planning. A true successor to the original Triumph Roadster, its development was beset by niggles and its production affected by poor quality control. A four-seater, the Stag occupies a rare market niche where the whole family can enjoy an open British grand tourer.

And were it not for the Meadows Frisky microcar, the Stag may never have happened. You see, the Frisky was the brainchild of Captain Raymond Flower, who held the Nuffield franchise in Egypt. He envisaged a small and economical car which would provide motoring for all, but with scant interest in Egypt he brought the idea to Britain. Meadows bit, and a number of Friskies were built in two distinct body styles. The design had been created by young Italian stylist Giovanni Michelotti, and when Flowers pitched his concept of a larger GT to Triumph, again Michelotti was his intended designer. Harry Webster was so impressed with the Michelotti “Dream Car” that he assigned all future styling work to the Italian on the spot.

The Stag was the result of Michelotti’s need for a 1965 Turin Motor Show star. A request was made to Webster for a used Triumph 2000 upon which to base it. Triumph agreed, on the proviso that if they liked the results they could have first rights. It was never shown at the Turin Motor Show as intended, as Triumph instantly whipped away the prototype to begin production.

Originally a full convertible, it was found to be too structurally weak. And so one of the greatest PR exercises of all time was carried out – that which was in fact bracing to hold the car together was sold to punters as a roll over bar to protect occupants in case of the car going all upside down. Fact was, it wasn’t strong enough to act as a roll cage – but it did the job of holding the door frames square under acceleration!

There are broadly three Stags to choose from – all distinguished by trim changes rather than any serious mechanical upgrades. The original Mk1 has steel wheels with rostyle trims, is fully colour coded and has no coach-lines. The Mk2 Stag of 1973 brought a black rear panel, clearer gauges, a coach-line and those GKN alloy wheels for which the Stag is well known. New seats and a revised hood were fitted, along with a slightly smaller steering wheel. In 1975 this was revised again – still called the Mk2, it lost the black rear panel and gained aluminium sill trims. Production ceased in 1977 with 25,939 produced – a fraction of the target, largely owing to the American market’s distaste for the Stag’s unreliability.

When new, a Stag owner would have been pretty well-off, though the task of keeping one in fine fettle could have been bankrupting if care wasn’t taken. These days, ownership is simple and inexpensive, and prices have finally started the upward swing which has been forecasted for the last two decades. Buying now would be clever.

Bodywork

Corrosion is the biggest enemy of the Triumph Stag – and while many have been restored, the quality of any work carried out is paramount. Assessing panel alignment and the fit of the doors is a good starting point. Rot can take hold pretty much anywhere, but you should pay particular attention to the front panel behind the headlights, inner and outer wings, the scuttle and A-posts, and the inner and outer sills. Replacing the latter can prove a tricky job and it’s not always done properly, so be especially wary if you suspect problems here; budget up to £1000 per side for complete replacement.

Plenty of time should be set aside to examine the chassis sections and floors, along with the jacking points and mountings for subframes and suspension. It’s also a good idea to lift the rear seat base, because if the metalwork is frilly under there you could be in for much worse trouble elsewhere. And don’t forget to assess the condition of the bonnet, bootlid, door bottoms and valances. The availability of various panels and repair sections does make a major restoration a viable proposition, but it will come at a significant cost.

The other area to address is the roof – with complete replacement not especially cheap, spend time examining the condition of the hood and frame and checking for perished seals. A hardtop is nice to have, but do inspect it for damage and corrosion as thorough refurbishment can cost four figures; check that it fits securely as well.

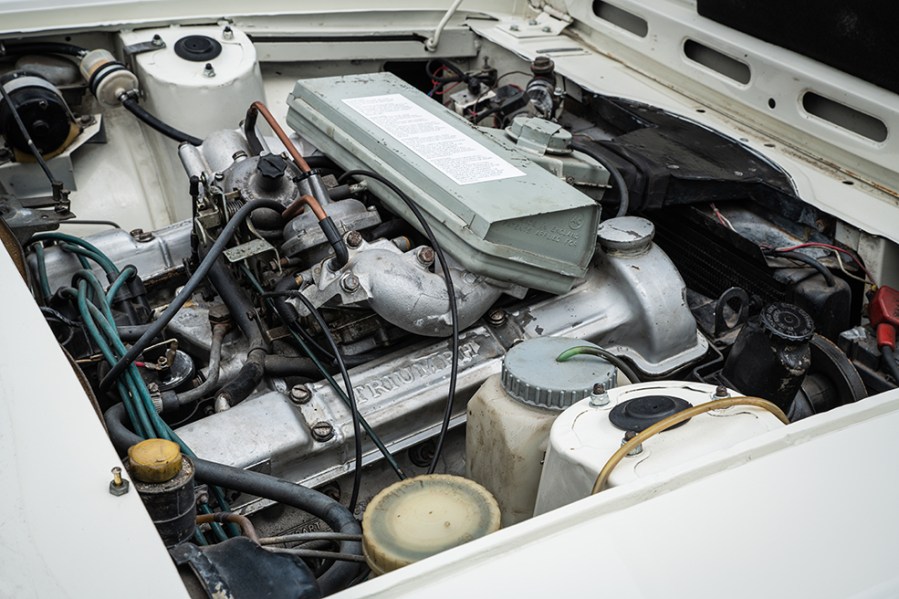

Engine and transmission

Much has been written about the Triumph V8’s propensity for trouble, with most problems stemming from poor manufacture and maintenance when the cars were new. The situation is very different today; with plenty of specialist knowledge out there, they can be made to run very reliably. Overheating with subsequent head gasket failure was one woe, but the likes of an uprated aluminium radiator, an electric water pump conversion and quality silicone hoses will keep things cool. Flushing the system and renewing the coolant on an annual basis will prevent corrosion of the alloy cylinder heads.

Timing chain issues are another oft-mentioned trouble spot; replacing them every 30,000 miles is a good move, usually costing around £600 at a specialist. Change the oil and filter every 3000 miles, too. Overhauling the fuel and ignition systems is a DIY task (ask the vendor about any upgrades), while replacing a corroded fuel tank with an aluminium item costs around £700.

A good engine can cover 150,000 miles before a rebuild is needed, a job that will set you back £6000 or more. While transplanting the Rover 3.5-litre V8 is a well-trodden path, reassure yourself that the work has been done properly. It’s a strong and well-understood unit with plenty of tuning potential if that’s your thing, but check for oil leaks, a tired cooling system and any signs the head gaskets have been compromised.

Turning to the gearboxes, there’s little of concern when it comes to the sought-after manual, although weak synchromesh and whining layshaft bearings are the usual giveaways of a unit ready for a rebuild. Check that the overdrive engages properly, too – it could be an electrical issue or low oil level rather than anything more serious, but a rebuild is £500-£600. Automatics arguably suit the Stag’s laidback nature, with three-speed units provided by Borg Warner – Type 35 at first, then Type 65 from 1976 – requiring a check for delayed or jerky shifts, fluid leaks, and treacly fluid in need of changing. There’s also the potential to swap the standard auto ’box for a ZF four-speed unit, a conversion developed by Clive Tate and Russell Lewis from the Stag Owners’ Club. Back axles can get noisy and leak oil, too.

Lastly, the driveshafts can lock up causing the ‘Triumph twitch’ while cornering if the splines haven’t been regularly lubricated; replacements using CV joints eradicate the problem and cost around £1200 per pair.

Suspension, steering and brakes

Stags should ride well – no worse than the 2500 saloon upon which they’re based. And everything is available to make the Stag ride and handle like it should – not only to original spec, but lowering springs, polybush kits, the lot. Whatever you want from your Stag can be made to happen – though cars that have been left standard are usually most desirable.

All Triumph Stag models left the factory with power steering. Steering racks can wear and introduce a wobble to the wheel that feels almost like wheel balance issues at first. However, plenty of companies can refurbish them and fitment isn’t difficult.

Check that van tyres haven’t been fitted to combat the difficulties of sourcing the correct size. Ideally, the best tyre for the job Is still the Michelin XAS, available from classic tyre specialists in the original late model size of 175HR14. However, if these are too much of a stretch to your budget, 195/65/14 modern car tyres are far safer than van tyres, whose stiff sidewalls and tread patterns offer less grip than you’d want.

As for the brakes, there’s little to report other than the need to check for wear and corrosion, the latter causing parts to seize. Check for the correct operation of the servo, but that aside you can source everything you need for an overhaul and there’s the scope for upgrades such as a vented brake disc conversion at around £1000. The latter will boost confidence in a Stag’s stopping power but a standard set-up in good order is fine for most situations.

Interior and trim

Contrary to popular opinion, the Triumph Stag interior was only ever finished in vinyl from the factory. While some magazines had seats in their press cars reupholstered in the nylon from the saloon – and any owners will have done too – Triumph felt that the expanded knit pattern vinyl was more likely to be effective against the uncomfortable truth of a British summer should the heavens open. Vinyl seat covers for Mk1 and Mk2 seats are still widely available new, as are kits to renew the foam.

Leather seat covers are a popular if non-standard upgrade, and many of the Stags you will see for sale are so trimmed. This isn’t undesirable but shouldn’t command a price increase. Moreover, more modern seats such as those from the Rover 200 Coupe or Jaguar XJ-S may even devalue your prospective purchase through their lack of originality.

Check that the wood hasn’t cracked, nor the veneer lifted. Kits are available, but at a price. And make sure all the symbols on stalks etc are visible. New heater surround bezels in particular are no longer available, and good ones are prized. Electric window switches can gum up and the protective coating can wear leading to UV damage, but at over £45 each for new ones many owners would prefer to refurbish damaged originals.

Most electrical problems are likely to be caused by aged wiring and poor electrical connections. It’s a good idea to systematically check everything, from exterior lights to switches and dashboard instruments, and log any items in need of attention. Electric windows are one specific thing to check – something as simple as lubricating the mechanism might effect a fix, but replacements are available if not.

Triumph Stag: our verdict

With so many examples of the Triumph Stag out there to choose from, it’s best not to get hung up on any particular example. We would struggle to picture a part of the country in which there are fewer than three or four for sale at any given moment, so buy on condition and be prepared to walk away.

Stags only ever came in one body style. Whether you choose to have a hard top or not depends in part on whether you want to use it in winter, in part on whether you like the looks and in part on whether you have anywhere to store it. The most valuable Stags still have the Stag V8 fitted – Ford V6 and Rover V8 engines devalue the model. Manual overdrive cars are popular but the box isn’t the best – they’re worth more than Borg Warner automatics, but cars retrofitted with the ZF four speed automatic remain the most valuable and desirable for regular use.

Stags are colour sensitive; those 70s hues such as Magenta and Topaz might appear amusing but they’re typically harder to shift than traditional British Racing Green, Carmine Red and White cars. The best compromises are Russet Brown and Mimosa Yellow if you want colours that are of their time yet retain an element of class.

If we were buying, we’d choose something in a good strong solid like red or green, with the ZF automatic gearbox and the original Triumph engine, and we’d get one with the best body we could get. That’s the sort of Stag that will bring the highest return upon your investment in years to come.

Triumph Stag timeline

1970

Triumph Stag launched in June

1972

High-pressure cooling system added and three-quarter window in soft-top deleted

1973

Changes to specification include light styling updates, updated instruments, new seats, a smaller steering wheel. Overdrive becomes standard

1975

Body-colour sills, rear panel and a stainless steel sill cover added to all cars

1977

Production ends with 25,939 examples made