The Escort Mk3 and Mk4 dispensed with the layout that had served their trusty rear-wheel drive predecessors so well, but went on to be huge successes. Here’s what you need to know when buying one today

Words: Christian Tilbury Images: Adrian Brannan

With the Mk2 Escort facing stiff competition from a new wave of hatchbacks, including its Fiesta stablemate that was actually more spacious inside, Ford gave its best-seller a radical makeover with the launch of the Mk3 version in September 1980.

Codenamed Erika, the Mk3 was now driven by the front wheels and the new body embraced the hatchback design, although there was the addition of a bustle that extended the tailgate with a hint of a conventional bootlid. Also brand new was independent rear suspension and the addition of Ford’s new CVH engine (Compound Valve Hemispherical) in 1.3 and 1.6-litre sizes, with the entry-level engine the Fiesta’s 1.1-litre Kent-based Valencia motor.

What was more familiar to Escort buyers was the choice of cooking trim levels – base (Popular), L, GL and Ghia – the majority of which were available in three, five-door and three-door estate body styles, with a five-door estate joining the range in 1983, plus a Cabriolet too. On top these, sporting variants included the new XR3 and subsequent XR3i, which came eight months after the limited-run RS1600i and was later sold alongside the boosted RS Turbo.

Engineered to keep maintenance requirements to a minimum, the Mk3 was incredibly successful and soon became Britain’s best-seller. So it was little surprise Ford took a very restrained approach when it came to giving it a mid-term facelift.

Announced in January 1986, it was codenamed Erika-86 and would commonly become known as the Mk4. Changes amounted to a sleeker, softer-styled front end, wraparound bumpers, reprofiled tailgate, smoother rear lights, the addition of a Granada-style dash and some worthwhile changes to the previously criticised suspension.

The changes worked to make the new Escort significantly more refined and the range-topping XR3i and RS Turbo were noticeably easier to live with and more relaxed than their Mk3 counterparts, however it was the cooking models that would make up the vast majority of sales.

There was a good selection of models to choose from too, the line-up spanning Popular, Popular Plus, L, GL and Ghia models. Engine wise, it was much the same as the Mk3, including the 1.6-litre CVH, 1.6-litre diesel and 1.1-litre OHV units, but there was now also the choice of a new 1.3-litre OHV motor and a 1.4-litre lean burn CVH.

Ford’s decision to tread carefully with the facelift certainly paid off and right up until it was replaced by the completely redesigned Mk5 in September 1990, the Mk4 continued to be a mainstay in the UK’s top 10 best-selling cars. However, the long-term lack of an enthusiast following for the normal models means that it’s easier to purchase a good RS Turbo or XR3i rather than, for example, a Popular. Here’s what you need to know.

Bodywork

Both the Mk3 and Mk4 are notorious for a rotten battery tray and surrounding bulkhead, but serious rust is also likely in the rear inner arches, rear chassis rails, floorpan, including the boot; behind the headlights and the front crossmember. More visible rust spots include the door bottoms, wings, the leading edge of the bonnet, roof gutters and tailgate, including around the hinges.

Be particularly wary of bubbling paint around the sunroof – it’s a sure sign that there’s significant rust underneath as a result of the drainage channels being blocked – and be wary of bodykitted cars hiding corrosion. Some panels and repair sections are available from Magnum Panels and are inexpensive but genuine Ford parts are getting expensive – reckon on circa £250 for a wing as opposed to just under £100 for a new pattern item. Replacement side mouldings, bumper overriders and end caps for the Mk3 are all hard to source.

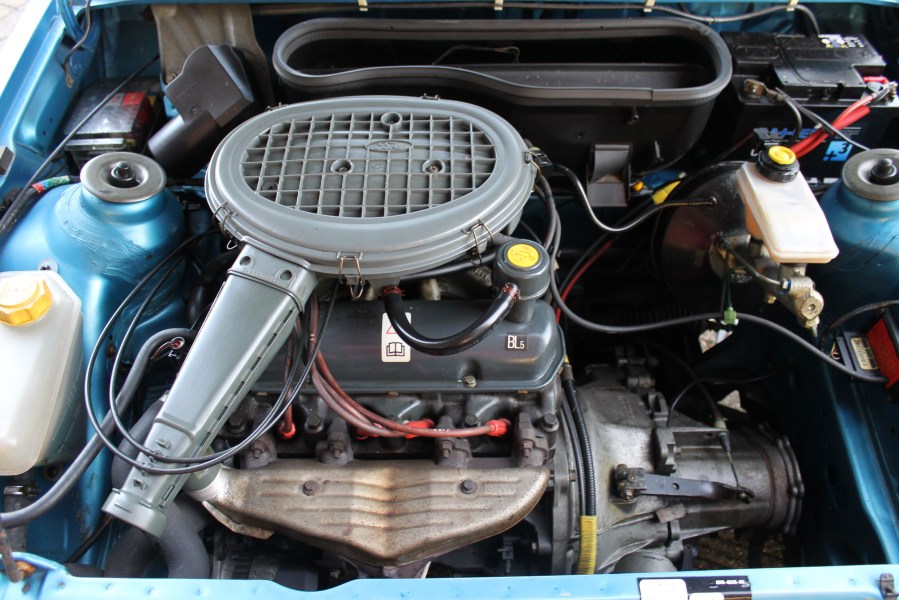

Engine and transmission

The CVH engines aren’t particularly refined but if the top end is rattling then it’s likely that old oil has sludged-up the hydraulic lifters and trashed the camshaft. A tired CVH will breathe heavy, although the often-perished rocker cover gasket can also leave oil over the engine bay. Blue smoke is another sign of a terminally ill motor, although if it’s on the overrun it can be the commonly worn valve stem seals. Cambelts should ideally be replaced every 20,000 miles, rather than the 36,000-mile interval that Ford originally stipulated, and while a good service usually sorts most running issues, the distributor can also be at fault as it’s prone to advancing too early. The RS1600i’s unique twin-coil ignition system can fail and be especially difficult to replace, so be extra vigilant on any reluctance to start, misfiring, or inconsistent running.

The Valencia 1.1-litre motor can cover a decent mileage if well maintained, but an excessively worn engine will have a noisy timing chain and breathe heavy. If the engine is tired it won’t like ticking over and while it’s never been the quietest unit, if it’s making an intermittent clacking sound it’s a sign of the camshaft followers having split and cracked.

The Variable Venturi carburettor on early models is infamous for various problems, from an erratic automatic choke to collapsed diaphragms, but many will have been converted in years since. Fuel injected cars can also present rich or lean running behaviour, often a sign of a seized metering unit – something that can be tricky to fix. The Bosch K-Jetronic mechanical fuel injection system fitted to the XR3i is more reliable than the later ‘90-spec electronic injection system, but some parts can now be difficult to source.

The BC Five-speed gearbox is slightly slicker than the four-speed, but both feel notchy. If finding gears is an issue then something’s amiss – usually with the linkage or, if there’s also jumping out of gear, the selector. Wear in the plastic ratchet that self adjusts the clutch can also cause gear selection problems, the tell-tale of advanced wear being a clicking noise when the clutch is engaged.

Both gearboxes can handle high mileages, but signs of obvious wear are any rumbling or whining, while worn synchromesh tends to be most likely on second and third gears. A noisy fifth often means the gear has come adrift on the input shaft and worn the splines. The RS1600i had a unique gearbox with a different fifth gear ratio and a limited-slip differential arrangement. This is a rarity and many have been converted to XR3 units in the past, so be sure to check it.

Suspension, steering and brakes

The Mk4 got tweaked suspension to further address the long-standing issues with the Escort’s damping and handling characteristics, but even so both the Mk3 and Mk4 don’t have the smoothest ride. If it appears to be overly harsh, then the dampers and springs are past their best – a simple bounce test being a good indicator of condition.

Track control arm bushes are commonly perished – tell-tales being vague steering and a clunking over bumps – and the usual and easiest fix is to replace the entire arm. It’s also essential to look for cracks around the mounting points of the TCAs.

Steering-wise, the rack isn’t the greatest, so listen and feel for irregularities when turning the wheel. However, a clicking sound on full lock will be more to do with tired CV joints.

Cars that have been stood present the most problems, the inactivity giving rise to seized wheel cylinders, sticking callipers and rusty front discs. All are easy to replace and cheap to boot, however. Brake pipes need close inspection too – after 40-odd years they’ve either already been replaced or are ripe for it. On Mk4s, the optional and harsh-in-operation ABS can be costly to fix, but otherwise it’s the same fare of looking out for warped or corroded front discs and seized components.

Interior and trim

Mk3 dashboards commonly crack above the instrument panel and around the heater vents. Look for the plastic warping around the central heater vents, while the glovebox lid of better specification cars also tends to bow. The Ghia’s door bins can crack around the mountings where they screw into the door cards. On Mk4s, the dashes don’t tend to crack but get misshapen on the plusher models, while the vinyl on the main door cards tends to lift.

Myriad trim colours and the fact that many lower-spec Escorts haven’t been considered to be worth saving in the past, means that replacing tired interior parts is difficult – something to remember if you’re a big fan of originality. Replacement trim can only be sourced second hand and while it’s cheap when it does surface, it’s a lot harder to find than that for RS and XR models. A good uncut parcel shelf can command a premium, however. Window rubbers can shrink and perish with age but don’t ignore a damp front carpet – particularly on the passenger side – as it’s a possible sign of serious corrosion in the battery tray and bulkhead.

In terms of electrics, rear lights can play up and faulty steering wheel stalks can cause lighting problems, but most electrical issues are simply down to age and are commonly cured with a clean of earths and connections. In particular, on plusher cars where there are faults with both the central locking and electric windows, the usual cause is the shared earth. Replacement lights are easily sourced and it’s relatively straightforward to source a factory stereo if it’s been changed.

Ford Escort Mk3 & Mk4: our verdict

With its predecessor valued so highly for so long, the Mk3 and Mk4’s time as affordable classics is surely limited – and by that, we mean the non-sporting models, as the ship has already sailed on the hot variants. For a relatively modest outlay you’ll get a practical classic with strong parts availability, but also a great conversation starter as folk remember the days when cooking Ford Escorts were everywhere. The Mk3 and Mk4 might not have the kudos of their rally hero forebears, but that means you get more for your money.

The high-performance Mk3 models are already highly desirable, especially the rather serious RS1600i, and the days of a cheap XR3 are largely over. The £722,500 made by the unique black RS Turbo driven by Diana Princess of Wales was a one-off, but a top condition stock RS Turbo can still command as much as £40,000. Today, an early carburetted XR3 can go for as much as £20,000, with an XR3i not far behind it. Mk4 XR3i and RS Turbo models aren’t quite as prized as Mk3 cars yet, but you can expect to £8000-£10,000 for an excellent example of the former and the best part of £20,000 for the latter in comparable condition.

Thankfully, non-sporting variants are far cheaper, though prices have risen. You’ll need at least £2500 for a useable Mk3, up to £4000 for a tidy car and above £6000 for the best. It’s still possible to buy a useable Mk4 for under £2000, with the nicer cars typically selling for £2500-£3000 at auction and the best cars heading towards £5000.