The Fiesta-based Ford Puma was a significant performance Ford but remains an under-the-radar gem. What’s it like to live with?

Words: Paul Wager

“You sure this thing’s based on a Fiesta?” asked the photographer, his white-knuckled grip of the seat betraying any attempt to appear calm as the autobahn signage flicked past at ever-increasing speed.

It was, to be honest, a fair question since by the time I’d replied our little convoy of Ford Pumas was nose-to-tail at some 125mph. The place was the A3 Autobahn somewhere near Frankfurt airport, the time late 1997 and the occasion the press launch of the first overtly sporty new Ford model for some time.

At the time I was editor of Fast Ford magazine and the readership was hungry for ever-more powerful modified examples of Ford’s turbocharged RS Fiesta and Escort, along with fast fords of the Cosworth era. Escort Cosworth production had ended the year before and it looked as if the RS badge was dead and gone.

Insurance issues played a major part of course, but Ford was also trying to up its game in the mainstream segment after the stinging criticism of the Escort Mk5 – as epitomised by Autocar’s cover slogan “The new Escort meets its rivals.. and loses.” To this end, Ford had invested heavily in updating its engine technology and in creating cars with handling to equal the French and German competition.

The first fruit of that programme was the 1994 Ford Mondeo, which was universally well received as a thoroughly modern Sierra replacement – but the one thing the range lacked was a model with any overt kind of sporty flavour.

With this abrupt change of direction, any new Ford with performance aspirations needed to be more subtle than the RS Turbo and Cosworth models, which underneath the bonnet vents and spoilers were all based on pretty ancient engine designs: the Pinto and the CVH.

To test the market for a new kind of high-tech, modern fast Ford, the company decided to start with a low-volume model but based on a mainstream platform – in this case, the Mk4 Fiesta which had launched in 1995 and had been critically acclaimed. A neat coupe body was created using Ford’s then-current ‘New Edge’ styling concept and the result was – if you squinted hard enough – like a shrunken Viper GTS from certain angles.

With its array of projector lights behind big smoked lenses and muscular haunches it had more aggression than the Tigra and little about its appearance suggested Fiesta. The details were well thought-out too, with the Fiesta-derived dashboard gaining a satin aluminium effect finish and the finishing touch being the machined aluminium gearknob.

The thing which really set the Puma apart from the competition though – and from any other Ford – was what they put under the bonnet.

Ford had already enlisted Yamaha to help develop smaller versions of its Zetec 16-valve engines for the Fiesta and the resulting 1.25-litre was a real screamer, making even the basic Fiesta fun to drive hard. Yamaha’s expertise was employed once more for the Puma, in which the engine was produced in a 1679cc guise complete with variable valve timing, and operated by engine oil pressure in a similar way to the Honda VTEC system.

Produced at the Valencia plant alongside the ‘regular’ Zetec engines, the 1.7-litre unit was good for 125bhp at 6300rpm and was a delightful engine to use, giving the 1039kg Puma useful pace. Maximum speed was 126mph and 0-60mph took 8.8 seconds – just a tenth behind the old Escort RS Turbo.

Despite the similarity in the bare figures, the Puma was really very different from the rough-and-ready blown Escort, and was aimed at a very different customer. It also delivered its power in a much more elegant way (even if the tuning potential was rather less) and when it came to handling had a poise which left the old Escort chassis floundering. In fact, I owned the legendary Peugeot 205 GTi at the same time and even my 1.9 GTi needed hard work to keep up with a well-driven Puma on a demanding road. This tells you all you need to know about how Ford had sharpened up its chassis engineering game.

At the car’s press launch, ride and handling guru Richard Parry-Jones – who would later rise to seniority in the global Ford empire – explained how the Puma, and later the Focus, had been engineered to provide the sharp turn-in and feedback of the Peugeots but without the ‘sting in the tail’ of those French cars.

True enough, the Ford Puma was a much easier car to drive fast than pretty much any other fast Ford that had gone before. The one criticisim road testers levelled at it was that it could handle a whole lot more power.

As it happened that was never to come, which was something of a shame. What we did get was the 1000-off Ford Racing Puma, a legacy of Ford’s rather awkward period in F1 after it had purchased the Stewart F1 team, and before the cars were rebranded in Jaguar colours.

The ‘FRP'(as it’s known to enthusiasts) was developed by Ford’s motorsport operation at Boreham but was put together by Aston Martin’s Tickford subsidiary in Northampton. Production Pumas were plucked from the line minus their front wings, which were replaced with bolt-on alloy items, while more major surgery was required to create the matching widened rear arches. New bumpers were fitted to suit and the car sat on 17-inch MiM wheels with 215/40 tyres hiding a pair of four-pot Alcon calipers and 295 mm discs.

The FRP had been teased as a motor show concept dubbed ‘ST160’ , giving a hint as to the engine upgrades. Courtesy of a pair of cams, replacement inlet manifold and tuned exhaust, the end result was 155bhp. That may sound rather tame compared to the wide-arched style, but it did make a noticeable difference to the driving experience and brought the 0-60 time down to 7.9 seconds. The Racing Puma’s engine management was also deliberately programmed to provide a crackling and popping exhaust on the overrun.

With a wider track and lowered, uprated suspension, the FRP traded some of the standard car’s great composure for a harsher, more track-orientated set-up, but was great fun. Inside you found Alcantara-trimmed Sparco buckets, while the outside was finished in striking Imperial Blue, now renamed Ford Racing Blue. Intriguingly for a low-volume special, that wider track (by 35mm front and 45 mm rear) also involved fitting longer driveshafts which made the wheel writhe amusingly in your hands over broken surfaces. A viscous-coupled LSD was offered but was really a specialist fitment for motorsport use.

As for the cooking Puma, that was given the 1.4-litre, 90bhp Zetec-SE in 1997 and later the 1.6-litre, 104bhp engine in 2000 – but production was destined to end in 2001.

Ford never really replaced the Puma and by rights it should be a surefire contender for modern classic status, yet it’s slipped under the radar. The modern-classic Ford attention is focused firmly on the older XR3i, RS Turbo and Cosworth models, while the Puma – which kick-started the revolution in Ford driving dynamics which led directly to the current ST models – is still lingering in the £1000–1500 bracket.

The Ford Racing Puma, meanwhile, never sold in the numbers predicted in the original brief, with insiders suggesting that around half of the proposed 1000-off production run were sold. Values of the surviving cars are already starting to climb, which tells you all you need to know.

All of this means that a presentable Ford Puma for the right money can be something of a bargain, and a really enjoyable yet affordable alternative to a more obvious hot hatch like the Peugeot 205 or Volkswagen Golf GTI.

Our Ford Puma project car

Words: Jeff Ruggles

When I drew a budget of £1000 out of the hat as my budget to buy one of a quartet of new Classics World project cars, I was dead-set on finding something fun to drive and reasonably quick. The initial plan was to find an Mk1 Audi TT but no sooner had I begun the search, I discovered a colleague had beaten to me to it.

There were a couple of conditions that had been imposed on us in our respective quests – each car had to be 20 years old as a minimum and had to have a current MoT with at least three months left to run. A rare last-of-the-line 1.6-litre Peugeot 205 in Bristol looked promising but was sold before I could view. Besides, I knew fellow staffer Joe Miller was keen on a Pug and it wasn’t really cricket to mess up his plans.

I know I shouldn’t really admit it, but the beauty of a challenge like this is that you’re spending someone else’s money. Despite the usual hairdresser’s car jibes, I’d always fancied buying a Ford Puma but had never pursued the idea due to fears that it would be riddled with rust and my investment would crumble away. Now though, the door was open to be take more of a risk, and so Ford’s often maligned Fiesta-based coupe went on my search list.

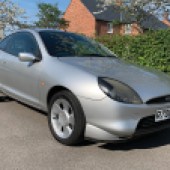

It simply had to be a 125bhp 1.7 model, despite warnings from our friendly local garage over the longevity of the Nikasil coating on the bores. It also had to be an early one; I’d seen plenty of post-2000 cars, but that was against the rules. I really wanted an early 1997 or 1998 car, and spotted a suitable Moondust Silver ’98 example down in Bude. That’s over two hours from me and it was considerably over budget, but I went to see it anyway.

It wasn’t perfect, with rust bubbling through on one arch, a dodgy idle, an inoperative radio, loose trim and a few MoT advisories to sort, but it did seem to be a very honest car. It had only had two previous owners – the first for 18 years – and had a had a history file thicker than a Yellow Pages from the 1990s. It also had under 70,000 miles on the clock and a recent cambelt change, but itwas the test drive that really swung it.

There was disbelief from those who drove the Puma on the press launch that it was based on a humble Fiesta, and my feelings were much the same 23 years on. If it wasn’t this one, I was set on buying a Puma anyway.

As it turned out, it very nearly wasn’t this one. The seller didn’t want to come down on price, and I couldn’t go over budget. But just I was about to walk away, the seller spoke of his other car, which just happened to be a Mk1 Mini. As I had some spares he needed, a deal could be done and my budget remained intact. Slight rule-bending, granted – and it was still a bit expensive for a Puma compared to others I’d seen – but I was convinced I was on to the right one.

Having quickly piled the miles on our new Ford Puma project car shortly after purchase, lockdown meant a change of pace, with use limited to weekly trips to Tesco instead. The sizeable boot means it’s quite well suited, but the ‘New Edge’ styling does tend to let rainwater run into the boot and all over your stuff.

Anyway, to make up for a lack of time behind the wheel, I caught up on some of the fiddly jobs that may well have been neglected otherwise. When collecting the car from the vendor, I noticed the door cards were loose.

I assumed this would simply be broken plastic clips, and promptly ordered a set of new ones. Some were indeed broken, but it quickly became apparent that the problem was not with clips, but with the plastic fittings that held them in place. These are usually glued to the door card but they’d broken away from the fibreboard, as had the rubber channels at the top that serve to hook the cards over the window aperture. So off came the cards, and out came the Evo-stik.

The non-genuine clips I’d bought were really a one-shot affair, so before I put the door cards back on, I decided to sort the disintegrated original speakers too. Fortunately, I had a spare pair of 13cm replacements hanging around, which although bright orange, had the benefit of being free.

With some new holes drilled and the clever use of Silent Coat sound deadening to fill any holes around their perimeter, clear sound was restored and the door cards could go back on. I make it sound easy, but fishing the remnants of the old broken clips out of the doors with barely any access was difficult and frustrating. Still, I was at least pleased to see that the doors were rust-free, and the repaired door cards haven’t fallen off yet, so that’s a win.

Externally, the car is pretty good save for an unsightly patch of rust emerging on one rear wheel arch – a trademark Puma grot spot. We hope to get that sorted somewhere along the line, but in the meantime a couple of quick improvements have been made.

The first was simply to go round with a touch-up brush and sort some of the stone chips, which should prevent any further rust for a while. The base of the roof mounted aerial was also looking rusty and untidy where the coating had come away. The solution? A bit of black wiring heat shrink and a lighter, which has improved things immeasurably.

One of the bonuses of the lockdown is that you tend to spend more time tidying, which in my case revealed a rotary polisher I thought I’d lost. That was just the impetus I needed to sort the cloudy, dull headlights.

So, armed with fine grade wet and dry, I removed the pitting on the plastic lenses, and then polished them back up to a shine. I feared the Meguiar’s Ultimate Compound I had to hand wouldn’t be abrasive enough, but it’s worked admirably. I still need to repair one of the rubber seals, but they look much better already.

Of course, we’re taking about a 22-year old Ford here, so there’s still a fair to bit to do. The remote locking doesn’t operate, despite my attempts to diagnose why. The stereo display also doesn’t work, so there’s the debate of finding another OE item, or fitting a modern Bluetooth item.

More pressing, however, is an oil leak. The MoT history advises of a power steering leak, but it looks more like engine oil to me. The culprit is likely to be either the crank seal or the rocker cover gasket, so I’m rather hoping it’s the latter – the part might be more expensive, but it’s a lot easier to fit. I can see some weeping from the gasket, so that looks like it’ll be next on the list. A return to regular use has also seen the exhaust develop a blow.

The current system looks like the original Ford system, so it’s lasted well until now. At under £70 it made financial sense to order a new pattern cat-back system, but that does mean the chrome tailpipe will be lost unless I manage to salvage it somehow. As soon as the weather makes its mind up, I’ll get cracking.

Small niggles aside, I’m becoming a real Puma fan and am delighted I’ve been given the justification to experience this one on a regular basis. I’m sure the rest of the team will appreciate it too given time, but I’m in no rush to relinquish the keys.