The evergreen Morris Minor is the classic everyone loves. We pay tribute to the first British car to sell a million

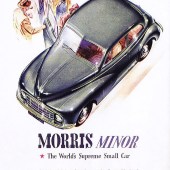

The launch of the new Minor at the 1948 Earl’s Court Motor Show marked a major turning point in the history of Morris, the company finally having an exciting new family saloon with which to boost its early post-war sales. It was Morris’ way of shaking off its outmoded pre-war image, gained via hastily reintroduced models like the Eight Series E, while at the same time offering Britain’s crucial export markets something genuinely fresh in terms of design.

From the earliest sidevalve-engined Series MM of 1948, through the 803cc A-Series updates and on to the eventual 1000 models, the humble Morris Minor was developed steadily throughout its career. Aside from the bestselling two- and four-door saloon versions, we were offered convertible (Tourer), estate (Traveller), van and pick-up models over the years, ensuring there was a Minor derivative to suit most buyers’ needs. And it was this versatility that helped it to enjoy an extremely long run, with the saloon bowing out in 1970 and the Traveller the following year, while the commercial variants remained on sale through to 1972.

The beginnings of the Morris Minor can be traced back to 1942, in the midst of the Second World War, with the first prototype appearing in the experimental workshops at Cowley early the following year. Nuffield Organisation – the owner of Morris – was planning its post-war activities even then, confident that a new, economical and affordable family-size car was the recipe for success.

The Minor would effectively replace the Morris Eight Series E and had to appeal to both Morris loyalists and those seeking a car utterly modern in its approach. Nuffield’s vice-chairman, Miles Thomas, realised that the young Alec Issigonis had huge potential when it came to designing the perfect family car, and tasked him with creating Project Mosquito. And so Issigonis set to, aided by the engineering talent of his two right-hand men, Jack Daniels and Reg Job.

The production car that was eventually revealed to an expectant audience at Earl’s Court in 1948 was a major step forward for Morris, although not as ground-breaking as Issigonis had anticipated at the outset. His original plan had been to equip the Minor with a brand new flat-four engine, a compact design that would have freed up extra space inside the car.

Prototypes of the newcomer were produced up until 1947 featuring this new flat-four powerplant, but the engine suffered from two major problems. First, there was an issue with vibration, although Issigonis and his fellow engineers insisted this would be cured during development; and second, Lord Nuffield was set against the flat-four concept, as Jack Daniels later explained: “As the flat-four ran into doubts, we would have liked to turn to the 918cc overhead-valve variant of the Eight engine, as used in the Wolseley Eight. But Lord Nuffield wanted a sidevalve engine.”

The engine used in the new Minor of 1948 was therefore the 918cc sidevalve unit from the previous Morris Eight, ensuring that despite modern touches like rack and pinion steering and torsion-bar independent front suspension, which together gave the newcomer an agile feel and superb handling, its performance was fairly lacklustre.

This issue of performance wouldn’t be tackled for another four years, when the merger between Nuffield Organisation and Austin to create BMC brought new opportunities. And top of the list was access to Austin’s brilliant new A-Series engine (as used in the A30), which found its way into the Minor in 803cc guise to create the new Series II range.

Adopting A-Series power transformed the Minor, and thanks to BMC’s ongoing development of the engine, the improvements kept coming. The 1956-on Minor 1000 was particularly significant, bringing BMC’s newly enlarged (948cc) version and an output of 37bhp. Then by 1962, a 1098cc derivative of the A-Series found itself under the bonnet of the little Morris, boosting its output to 48bhp at 5100rpm.

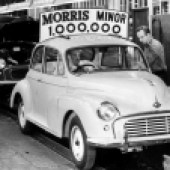

Towards the end of the 948cc version’s run, in February 1961, the Morris Minor became the first British car to sell over a million units – a remarkable feat that was achieved in less than 13 years. To mark the occasion, BMC launched a limited edition of just 350 Minor two-door saloons (representing the number of Morris dealerships in Britain at the time), each car finished in lilac with a white interior and featuring ‘Minor 1,000,000’ badging.

Much like the Volkswagen Beetle, the final versions of the Morris Minor looked broadly similar to the first. There were, of course, external changes over the years, not least the raising of the headlamps from the grille to the redesigned front wings in 1950, followed by the move from split-screen to single windscreen, enlargement of the rear window, reshaping of the front grille and numerous other updates.

You only have to glance at an early Series MM and a late-model Minor parked together to realise that they’re close-knit members of the same family. And yet, thanks to the many updates that took place under the skin, the difference in driving styles between the earlier and later Minors is significant, even if the nimble feel and tenacious handling of both cars will be familiar to anyone experienced in Minor motoring.

One surprise of the Minor’s early career is just how long it took for an estate version to arrive, with the Traveller not appearing until 1953. But that doesn’t mean it wasn’t always on the drawing board. In fact, Alec Issigonis, Jeff Daniels and other BMC engineers were working on the project long before it came to production fruition, with development of estate car versions of both the Minor and the larger MO-series Oxford occurring simultaneously. It’s not surprising, therefore, that what would come to be known as the Morris duo of Travellers Cars would follow broadly similar rear-end designs.

The idea of using wood as part of the new estate’s strength and structure might seem odd now, but 70 years ago it was understandable given what was happening across the Atlantic. The idea of a woody was an unashamed American influence, this being the era when British car designers were adopting the style and creativity of their US counterparts. The end result was a car that used the front end of the Minor saloon mated to a rear based around the existing floorpan but featuring a structural wooden framework, aluminium rear roof section, twin side-opening rear doors and a generous load area.

The choice of an ash framework made production sense, too, as this was a material readily available in 1953. Strength was also an issue, with the Traveller’s wooden roof cant rails bringing together a structure of impressive integral strength. Even better, the existing wood shop at the Morris Bodies plant was capable of taking on the task of putting together the timber framework, which was then transported to the Minor production line at Cowley ready for final assembly of the finished vehicle.

Sadly, the Minor Traveller was not the profit-generating model it should have been – although this certainly wasn’t through lack of sales. The problem was that despite assembly of the Traveller’s wooden framework being an in-house affair, it was a labour-intensive process. And that meant zero profit, as former Cowley manager, Eric Lord, recalled some years later: “The only Minor we never made any money on was the Traveller. Every one of those we put together we lost money on. By the time we’d bought the body, brought it in and assembled it, it had cost us money. If we’d put it together for nothing we’d still have lost money on it. I could not get the sales people to put the price up. Which was ridiculous – because the car was selling quite well, really.”

If the Traveller never made a profit for BMC, it certainly contributed to the overall success of the Minor range, with more than 215,000 examples sold. That the Minor Traveller survived through to 1971 proves just how strong its loyal (but gradually diminishing) following was, even in its later years.

Morris Minor myths debunked

“Most Morris Minor vans were sold to the Post Office and all featured rubber front wings to prevent damage”

In fact, out of the 326,609 Minor vans and pick-ups produced over almost 20 years, a total of 52,745 went to the Post Office as part of their fleet – a large number, but still a relatively small proportion of total Minor commercial production. Meanwhile, the famous rubber front wings of the first GPO vans gave way to conventional steel items as early as 1955. Perhaps more oddly, the GPO demanded use of the 803cc engine for their vans until 1964, when they finally accepted the 1098cc lump; no 948cc Post Office vans were ever produced.

“The estate version of the Morris Minor was called the Traveller throughout its career”

Not quite. When it first went on sale in October 1953, what we now think of as the Minor Traveller was initially called the Minor Station Wagon. But that moniker lasted just a few months; by mid-1954 it was rebranded as the Minor Travellers Car, a name that was subsequently abbreviated to the better known Minor Traveller.

“The Morris Minor wasn’t as successful as the Mini, Issigonis’ other legendary design”

In absolute terms, that’s correct. The Mini enjoyed a 41-year career and sold almost 5.4 examples during that time. By comparison, the Morris Minor was on sale for 34 years (the saloon being dropped in 1970, but the Traveller and commercials remaining on sale until 1971 and 1972 respectively) and achieved a production figure of around 1.3 million. Remember though, that the Minor was the first British car to sell more than a million units (a feat achieved as early as February 1961), and so deserves its place in the history books as one of the most successful UK-built cars of all time.

“The only commercial Minor models were the van and pickup variants”

Well, not quite. Among the overseas plants that assembled the Morris Minor during its lifetime was one in Denmark. And part of the Danish (and Scandinavian) line-up was the Morris Minor Combi of 1959 – a version that managed to be priced at one-third less than the regular Traveller (renamed the Morris 1000 Super Stationcar by the time the 1098cc version came along) thanks to steel panels where the rear side windows should have been. The back seat remained in place, yet the resultant tax concessions – which saw the Combi officially classed as a working vehicle rather than a family car – made the whole project well worthwhile.

“Austin-badged derivatives of the Minor van replaced the Morris version in the 1960”

BMC did indeed introduce a version badged as the Austin 6cwt Van in 1968, a full 15 years after the very first Morris Minor Van. It was launched to give Austin dealers a replacement for the outgoing A35 Van, and featured a traditional Austin-style ‘crinkled’ front grille. Production of all Minor-based commercials ceased in February 1972.

“The Morris Minor was put back into production in Sri Lanka via a connection with Charles Ware’s Morris Minor Centre”

This was certainly the rumour doing the rounds in the early 90s, when Charles Ware’s Morris Minor Centre – a company that had been catering for the needs of Morris Minor owners since 1976 – set up a factory in Sri Lanka, going by the name of The Durable Car Company. And it’s there that brand new panels were produced by a skilled workforce, with over 80 different chassis and body panel sections being made for export to the Morris Minor Centre. However, initial suggestions that the factory would eventually end up producing brand new Morris Minors proved unfounded.