Handsome and great to drive yet often forgotten in the shadow of its more famous rivals, the Sunbeam Alpine is a solid leftfield choice

Words: Iain Wakefield Images: Matt Woods

When it was launched back in 1953, the original body-on-frame Sunbeam Alpine was introduced as the ‘Queen of the Sportscars’. The Rootes Group marketing department needed to come up a new mantra for the unitary-constructed Alpine unveiled six years later in 1959: ‘Sleek – Swift – Spectacular’ was the eventual description that accompanied the introduction of the Series I Alpine for the all-important US market.

Introduced to compete with similar sporting offerings from the likes of MG and Triumph, the Raymond Loewly-styled Sunbeam Alpine featured wind up windows, a rarity for at the time in a two-seat sports car. The suspension and powertrain were all borrowed from either the Hillman Minx’s or Series III Rapier’s parts bin, while the floor pan was a modified version of the structure used for the Hillman Husky.

Under the Alpine’s sloping bonnet lurked a 1494cc inline-four rated at 83.5bhp driving the car’s semi elliptic sprung rear wheels through a four-speed gearbox (optional overdrive was available). Steering was by a Burman recirculating ball set-up and the Alpine’s front suspension comprised of double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers and an anti-roll bar.

In October 1960 Rootes introduced the Series II Sunbeam Alpine with a slightly more powerful 1592cc engine rated at 80bhp at 5000rpm, while retaining the same front grille as the early model. In January 1961 the coachbuilders Harrington produced a coupe version featuring lopped off rear wings and a sloping glass fibre roof. In October of the same year Harrington produced a limited number of now highly desirable and very expensive Le Mans badged Alpines.

In March 1963 Rootes launched the third version of the good-looking Sunbeam Alpine. Although the Series III Alpine still retained the large rear tail fins, the side drop glass was now squarer to make getting in and out of the car easier and some versions were now fuelled by a pair of Solex carbs in place of the twin Zeniths. The Series III was available in two body styles – the canvas topped Sports Tourer or the factory hard top equipped GT.

Although the better equipped GT enjoyed the luxury of carpets instead of the Tourer’s rubber floor and boot mats, there was no room behind the seats to store an alternative hood, although some cars on sale now will have been suitable modified. The dull silver painted dashboard fitted to the earlier Tourer was replaced by a black plastic finish and extra creature comforts found in GT versions included a wooden rim steering wheel, walnut veneered dashboard, decorative vinyl door cappings and patterned door cards.

Both the Tourer and GT enjoyed the benefit of more usable boot space made possible by replacing the single boot floor located fuel tank with a pair of linked tanks mounted inside the rear wings and storing the spare wheel vertically against the rear bulkhead instead of on top of the tank.

It was all change again in early 1964 when Rootes introduced the radically different Series IV Sunbeam Alpine featuring trimmed down rear fins with new light clusters, a slatted front grille in place of the previous model’s single bar affair. Optional automatic transmission for the first time and an all synchromesh gearbox was available from late 1964.

Changes carried out between the Series IV and IVA models are slight and include squared off corners on the doors, bonnet and boot, unleaded panel joints, a revised flywheel and clutch assembly and a different gear lever reverse gate, which required the lever to be pulled towards the driver and back. The final version of the Sunbeam Alpine, the Series V, Sports and GT broke cover in late 1965. Power now came from a 92bhp rated 1725cc five-bearing inline-four fuelled by a pair of Stromberg down draught carbs.

The larger engine now gave the Alpine a top speed of 118mph and a 0-60mph sprint time of 11.5 seconds. Revisions to the Series V also included fitting an oil cooler, alternator, and footwell vents, while very late Series V Alpines are identified by having no peaks on the headlamps and a Chrysler ‘Pentastar’ badge at the base of the near side front wing. Alpine production ended on January 1, 1968 and over the years this popular Sunbeam has made countless appearances on the silver screen and is credited as being one of the first Bond cars when a Lake Blue example was driven by 007 in the 1962 film ‘Dr No’.

Bodywork

Without a roof holding the front and rear box sections together, it’s vital to ensure the bodyshell is structurally sound on any Alpine being viewed. According to the Sunbeam Alpine Owners’ Club, one of the first question to ask the vendor is: “Can the car be jacked up using one of the rear jacking points?” If the answer is “Yes”, then being able to open and close the doors without catching when the car is up in the air is a pretty good indication that all is well with the monocoque.

However, that test shouldn’t rule getting under the car and inspecting the condition of the ends of all the box sections, including the reinforcing cruciform at the rear of the chassis as well as the front mountings for the rear springs. Other places to check for corrosion are at the leading edge of the front wings over the headlamps, front and rear valance, inner and outer rear wheel arches, inner wings, bulkhead seams, boot floor and lid, sills, floors and front chassis legs.

The exhaust is made up of several small pieces and runs through a cross member and can corrode badly. Rust can attack the top of the scuttle in front of the screen, so check for any bumps that could indicate corrosion is trying to force the panel apart.

When viewing the car from the side, ensure the bottom edge of both doors line-up with the sills and that the doors don’t stick out at the rear lower corner. Check the quality of any obvious structural repairs and the paintwork for any ominous bubbling or finish spoiling micro blistering.

Lead loaded body seams on the Sunbeam Alpine were dropped gradually from the Series III onwards, so panel gaps (sills, etc) should really only be visible on later models. Hinge mounts of Series I and II cars can rot badly and this area is difficult to repair, while screen surrounds on Series III to V cars can rot.

Also remember that some hard-topped equipped GTs may have been retrofitted with a hood and when inspecting the soft top, make sure the seals are correctly located around the rear edge of each door glass. If it’s a later GT (Series III to V), the hard top will be made of steel, rather than aluminium, so make sure it isn’t rusty, especially around the hard to inspect base.

Engine and transmission

The first thing to establish is what engine is fitted to the Sunbeam Alpine being viewed. Is it the original, or has a slightly more powerful 1725cc unit been fitted instead? This can be confusing, as the earlier cylinder head fits the larger block but the best way to check is by looking at the dipstick. On the larger engine, the dipstick goes directly into the block just behind the oil filter. If the engine has an iron head, it’s from a Minx series car, while some Alpines may even have a ‘Holbay’ motor taken from an H120 Rapier, so check the paperwork carefully.

Evaluating the condition of an Alpine’s engine will be much the same as for any classic powerplant of the era. Check the coolant for signs of any milky looking residue, which could indicate coolant is mixing with the engine oil due to a faulty head gasket.

Blue smoke from the exhaust will indicate worn bores and/or rings and loose tappets – a sign that servicing may have been missed – will make themselves heard. Oil pressure should be above 50psi at 2000rpm on a hot 1494cc or 1592cc engine (25psi at idle) and 40psi on the 1725cc unit.

Note that Series I-II Sunbeam Alpine examples have a cross flow radiator featuring an alloy header tank located in front of the cylinder head, while other models have a more conventional system. If the car has an electric fan, check whether it’s manual or automatic and that the engine isn’t overheating.

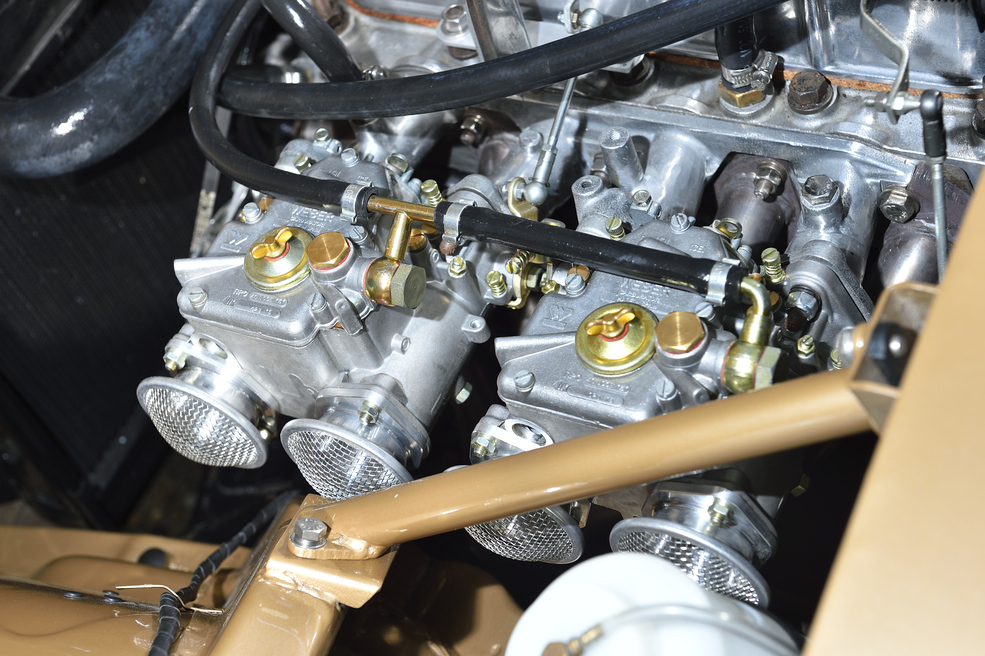

While checking the engine for leaks, any coolant dripping down the back of the block is bad news, as this will probably coming from a corroded core plug. By now many cars will have lost their original carburettors and been replaced with a pair of Webers mounted on a Series V inlet manifold.

Manual gearboxes fitted to the Sunbeam Alpine are generally extremely long lived and the good news is that rebuild kits are available. A Laycock de Normanville overdrive unit was offered as an optional extra and later Series IV and V cars will have an all-synchromesh gearbox, although one could have been fitted to an earlier model.

Any rumbling from the gearbox can indicate worn bearings and jumping out of gear will be a sign that the box is ready for an overhaul. Automatic gearboxes should swap ratios cleanly and the fluid should be bright red and not brown.

A non-functioning overdrive unit (only works on third and fourth) could be down to an electrical glitch or worn servo seals, while a slipping clutch and a leaking master or slave cylinder can be a good negotiating point.

Suspension, steering and brakes

There’s nothing complex about the Alpine’s suspension and steering set-up, although Series I-III cars have kingpins that require regular greasing, while later models have bushes that don’t. Early models have lever arm shock absorbers, and these should be inspected for efficiency and leaks.

There are lots of joints to inspect between the steering box and the front wheels on the Sunbeam Alpine. Get an assistant to gently rock the steering wheel back and forth while checking for any slack in the joints. Try to move the swinging link below the steering box (it shouldn’t move up and down) and if the car’s caster angle seems to be incorrect, this will be down to the alloy wedges situated under the front subframe being corroded.

Checks to the rear suspension should concentrate on the condition of the leaf springs (which should be almost flat when the car is parked), shackle mountings, bushes and shock absorbers.

Check the condition of the front discs and pads and note that Series III-V had vacuum servos fitted as standard (either a 5 or 7-inch unit located in the right-hand corner of the engine bay). By now all the car’s original steel brake lines should have been replaced with either copper or conifer lines, so look carefully for any weeping joints and calipers. Fluid stains around the backplates on the rear drum brakes will indicate a leaking wheel cylinder, which will probably mean the brakes shoes are contaminated with hydraulic fluid.

Interior, trim and electrics

The main things to check are the general quality and fit of all the interior, and note if any items are missing or unappropriated modifications have been made. While all models had carpet on the transmission tunnel, Tourers had rubber mats, which by now will probably have been replaced with carpet.

The black plastic dash top can become detached from the scuttle and note that Series I-II Alpines had a gunmetal grey coloured dashboard. Later models had black plastic covered dashboards (the glovebox never had a lid) and Series III GTs came with a wood veneered dash. If the driving position doesn’t feel right, the Alpine’s pedals can be set in two positions and Series III-V cars have a forward/aft adjustable steering wheel.

Check the heater controls all move easily and that all the instruments and the horn work. Lucas supplied most of the switch gear for the Sunbeam Alpine, which means sourcing replacements shouldn’t be too much of a problem. Although the electrics on these cars are basic by modern standards, any damaged or badly modified wiring can be a problem that is very often best cured by fitting a new loom, a job that looks complex but can be undertaken by a competent owner. First port of call for replacement trim should be the Sunbeam Alpine Owners’ Club for full details of appropriate suppliers.

Sunbeam Alpine: our verdict

While the early Alpine’s Studebaker influenced styling is often considered visually pleasing, the mechanical refinements built into the later cars can make them easier to own and maintain. The Alpine will be remembered as one of the first mass produced British built sports cars to replace leaky lift-out side screens with wind up windows, for example.

A well-sorted example with an overdrive gearbox and fuelled by a pair of modern Weber carbs provides a comfortable way to enjoy classic motoring, whether it’s an early convertible or later hard-top equipped GT.

Sunbeam Alpine timeline

1959

Production of the Series I begins

1960

Series II Alpine arrives with 1592cc engine and revised rear suspension.

1963

Series III Alpine introduced in March, available in two bodystyles: GT and ST

1964

Series IV sees lower-power engine scrapped and the characteristic fins of the Series III reduced in size. Automatic gearbox introduced as an option

Sunbeam Tiger enters production based on the Alpine and featuring Ford V8 power

Sunbeam Tiger

1965

Series V brings new twin-carb 1725cc engine and removes auto option.

1967

Sunbeam Tiger Mk2 introduced in the US market only

1968

Sunbeam Alpine Series V production ends

1969

Sunbeam Alpine name revived for the Rootes Arrow range, based on the Sunbeam Rapier