‘Backdating’ is all the rage these days. But is it really worth doing? We looked at these two iconic classics to help make our minds up.

It’s funny how trends change. In days gone by, enthusiasts have moved heaven and earth to make their cars look newer than they really were. Remember those pre-’53 Volkswagen Beetles with the charismatic two-piece rear screens? Well, when the one-piece ‘oval’ screen appeared there were DIY articles published on how to cut the central bar to get a similar contemporary look. With values of those rare, very early cars having gone through the roof recently, you can imagine how anyone who butchered their Beetles in that way must be feeling right now!

Today, visually at least, things have gone the other way. In the last few years there’s been a rush to put a ‘retro’ spin on a car to make it more closely resemble its ancestors. More ‘classic’, if you like. It’s a relatively simple concept to grasp; by swapping wings, sills, mirrors, bumpers and the like the clock can effectively be turned back to make a car look a lot older than it really is.

Underneath, things are less clear-cut. Usually, fitting mod cons such as electronic ignition, an alternator instead of a dynamo or retro fitting disc brakes from a newer model is the chosen option. That said, with cars inevitably getting more complex as time passed by, it’s not unheard of for owners to rip out a troublesome fuel injection system in order to fit carbs or throttle bodies instead. Just think of the TR6 owners who’ve imported a PI car from the States then fitted twin SUs for better economy and reliability.

The fear when ‘backdating’ is that you’ll end up with a bit of a dog’s dinner, neither one thing or the other. And then there’s the matter of value, and how much straying away from original spec may hurt come resale time. To help consider some of the other factors involved, let’s take a closer look at two cars where turning back time might seem like the obvious thing to do.

MGB

The still relatively ubiquitous MGB went through a number of changes in its lifetime, the most controversial, undoubtedly, being the addition of black polyurethane steel bumpers in place of the delicate chrome affairs in 1974.

But it wasn’t just the bumpers that were swapped, the ride height was raised 1.5 inches and it gained 100 pounds in weight – which had a less than complementary effect on handling with the roadster being particularly badly hit by roll-induced oversteer.

With this in mind, you can understand why there might be a strong incentive to take them off and fit chrome items instead, different springs and spacer blocks at the back to get a newer MGB looking like it once did. However, according to the people we spoke to, very few people actually do it.

According to the MG Owners’ Club workshops at Swavesy, on average they do roughly one chrome bumper conversion every couple of months. “We get a lot of enquiries over the ‘phone, but very few take it up when they find out the price,” they told us. At £3300 plus VAT, it’s certainly not cheap.

Steve Hall from MG specialist Hall’s Garage in Bourne, Lincs, told us a very similar story. “We haven’t done one for ages. There’s quite a bit of work involved, it’s not just a case of bolting on new bumpers. You need to weld sections into the front and rear wings, which means painting four panels, and often the grilles don’t fit. Also, you need to be careful if a rubber bumpered car has been fitted with a reproduction bonnet; they’re often too flat across the top and with a chrome bumper conversion there will be big gaps either side.

Either way, Steve’s less than convinced about the end result: “You’re on a hiding to nothing to be honest; you’ll get a hybrid that won’t be worth nearly as much as a chrome bumpered car, and only a little more than a rubber-bumpered model. You won’t get back the cost of the kit if you do it properly.”

Another MG specialist, Former Glory, was equally sceptical. “Despite the fact that nine times out of ten people prefer the classic look, it’s not really necessary in my opinion. If you were to do it, I’d say it would be better on an early car – an N or P-reg with the metal dash – than a later MGB. It would look a bit odd on an X-reg.”

Despite all this, when you consider retail values, there’s a convincing argument for backdating a late car. Steve Hall reckons a rubber bumpered Roadster will struggle to make much more than £7,500-£8,000, while a genuine chrome bumpered model will be roughly twice this.”

The problem is, a converted rubber bumpered car will always been just that – a converted later model. Steve Hall has a possible compromise: with a rubber bumper MGB, why not fit a Sebring rear valance instead?”

In our opinion, there’s lots to commend the later car. Overdrive was made standard from 1975 and from 1977 the front and rear valances were painted black to help the new bumpers blend in better. Additionally, a new dash was added with better-positioned heater controls, new column stalks and more petite four-spoke wheel. Oh, and lower geared steering sharpened up direction changes and crucially the fitment of front and rear ant-roll bars to improve the handling.

Porsche 911

In case you hadn’t noticed, early 911 Porsche values have sky-rocketed over the past few years. In fact, you’ll struggle to find a pre-impact bumper example for much less than £80,000.

That makes the case for backdating one of these supercar icons rather compelling doesn’t it?

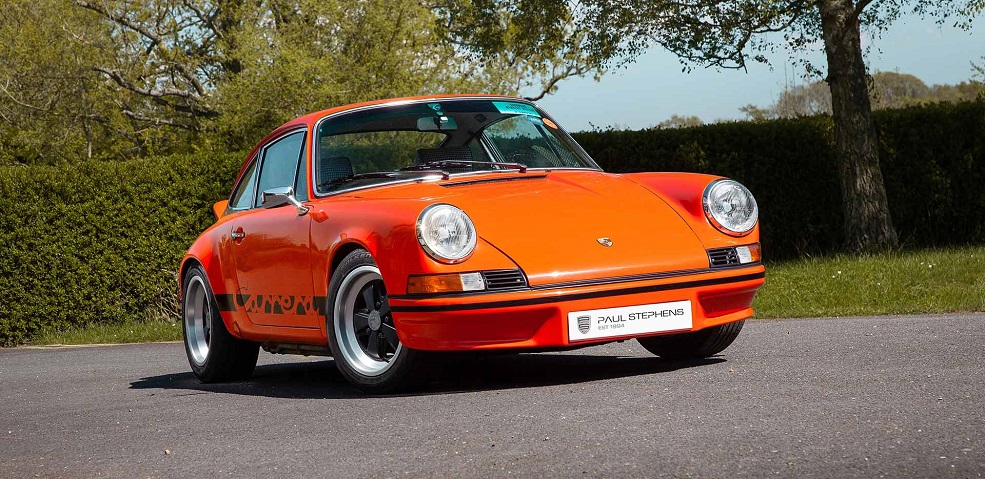

Well, that’s exactly what Essex-based Porsche specialist Paul Stephens reckoned a few years back. Ahead of the game in many respects, they once sold complete glassfibre kits which included bumpers, sills, mirrors, chrome trim and all the items necessary to make a then relatively affordable 964 Carrera 2 look just like a highly sought after pre-’73 car. Things have moved on a notch since then at Paul Stephens. They no longer sell the kits; instead they custom build later 3.2s and SCs into older, more classic looking 911s using all steel panels as part of their Classic Touring Series. The cars are fundamentally built from scratch with a raft of upgrades to bring them bang up to date mechanically. Identifying the 2.2 and 2.4 models from 1970-73 as the ‘prettiest cars Porsche ever made’ they have, as their website states, “been created for the discerning owner who appreciates the authentic timeless style of the 911 from this period, but seeks increased refinement and attention to detail, in a car that is suitable for daily use.”

As the firm’s Tom Wood explains, it’s actually a good way of preserving cars that would otherwise have been scrapped long ago. “On some impact bumper donor cars, if the panels are too far gone and the engines are shot, they are beyond economic restoration. Here, a complete strip down and revision gives these cars a new lease of life.” There’s a price to pay though for this level of bespoke build, with prices starting at £250,000.

As for the DIY option for those with a smaller budget, there’s still an opportunity of fitting fibreglass panels to make an impact bumper 911 look older – the internet is awash with wings, sills and bumper kits to make it possible. The same goes for the inside, too, with old school seats, dashes and steering wheels all giving a more modern 911 a more retro look when behind the wheel.

Now, Porsche buyers are a fickle lot so you’d think by messing about with the original would hammer values. But this isn’t necessarily the case according to Tom. “There’s a keen interest in these cars, although the market responds to how well the work has been done.”

So there you have it. With the 911, do the work to a high standard and the rewards may well be worth it.