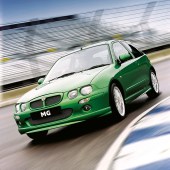

Despite unglamorous origins, the MG ZR brought the spirit of the octagon into the 21st century – and it still cuts the mustard 20 years later

The ‘R3’ variant of Rover 200 which arrived in 1995 was essentially a new Rover design, but one which contained considerable carryover from the previous Honda-derived cars – in essence the platform consisted of the front half of the previous ‘R8’ 200/400 (also known as the Honda Concerto) while the back half was from the R8 but heavily modified to provide more boot space and to accept the cheaper torsion beam rear axle from the Austin Maestro.

The 200 was facelifted as the Rover 25 in 1999, which in turn spawned the MG ZR in 2001. To effect the metamorphosis from staid Rover into sporty MG, the ZR was given a revised bumper, grille and a tailgate spoiler. The MG also got lower and stiffer springs, harder bushes, uprated dampers and sharper steering. The result was a well-handling car that could be thrown into corners with enthusiasm, providing plenty of feedback to the driver and sticking to the road like a true GTI.

The ZR was facelifted in 2004 with minor external tweaks, most obviously the switch from a four- to a two-headlight look and more extensive changes to the interior. The facelift version was perhaps not as pretty, but it benefitted from tweaks that made the brakes, throttle and suspension all feel even sharper.

The ZR was available in three and five-door bodies, and in two trim levels: ZR and ZR+. The Plus got extras such as electric front windows, a sunroof and better seats, while the ZR160 also gained aircon, bigger alloys and sculpted sill finishers, the latter two being extra cost options on the lesser models.

Engine-wise, there were three petrol options and two diesels. Entry level was the ZR105 with a 103Ps 1396cc K-series and a five speed R65 manual gearbox that had been developed from a Peugeot design. In mid-2003 that was replaced by the Ford-derived IB5 5-speed gearbox similar to the one found in a Fiesta. The ZR120 got the 1796cc 117Ps version of the K-series engine, now attached to a Honda-designed PG1 5-speed manual or a ZF CVT automatic option, while the ZR160 got VVC on the 1.8 engine and 160Ps with a model-specific closer ratio version of the PG1. The majority sold were ZR105s, and the extra power of the ZR160 over the ZR120 is only really noticeable if you regularly venture into the upper rev range.

The diesel TD option was powered by the 1994cc L-series, putting out either 101Ps (discontinued on the Mk2) or 113Ps according to the programming. Both were turbocharged, but not exactly state of the art engines, being descended from the old Perkins Prima diesel unit found in the Maestro/Montego, itself developed from the BL O-Series petrol engine designed in the early 1970s.

All ZRs were blessed with the same basic suspension package, but with different front spring and damper rates to cater for the 100kg K-Series petrol engine or the 180kg L-Series diesel. Brakes were 260mm discs at the front and drums at the rear for the low powered models, but front discs were vented and 240mm solid rear discs fitted on the ZR120 and the higher power diesel. The ZR160 had even larger 282mm vented front discs with 262mm solid discs at the rear clamped by larger calipers. It also got ABS as standard, while this was an extra cost option lower down the range until later in the production run.

Bodywork

The good news for anybody expecting a lifetime of welding on any MG costing just a few hundred quid is that ZRs are generally pretty robust bodily, and rust is unlikely to be a serious issue. In general the build and material quality declined over the ZR’s production run, so earlier cars are less susceptible to issues…but then they’ve also had more years for the rust to get a hold. The general quality took a particular slump with the 2004 facelift, when all sorts of materials, fittings and production methods were cost-cut as MG Rovers finances continued to spiral.

The main area to check are the front wings around where they meet the front bumper, which collect moisture on both sides. Bubbling paint is the first sign of trouble. New wing panels are available for around £130 per side, but will require painting and fitting. The wheel arches are all prone to rust, with the rear ones being the first to go – first on the inner wing surface, then the outer, so be sure to look and feel for previous patches put in here. The particular trouble spot is rust breaking through between the inner arch and the outer wing panel.

Rust around the boot lid hinges is another problem, especially if it spreads from there to the roof panel – a repair panel for this area is available. The boot lid panel itself often rusts around the release/lock button, especially on later cars where rubbing keys scratch through the paint. The bonnet can rust on its leading edge and wherever stones or debris have chipped the paint. In general the ZR is prone to start rusting wherever the paint has been broken, be it by outside action or around badges, locks, door handles or repeater lamps.

The steering and front suspension is carried on a subframe (more of a large crossmember) – these are not especially prone to corrosion, but it does set in on cars that have seen a lot of use on rural roads or near the sea, and is more often seen on later cars with poorer paint application. Rust can also take hold where this bolts to the extruded body members, which is more serious but can still be repaired fairly easily.

The sills are generally resilient, but will rust after enough miles and years; they tend to go at the back first, often meeting up with rust in the inner rear wing if it’s bad enough. Also check around the kick plate on the upper sill, since this can also harbour rust.

Despite middling material quality, the fit and finish of the body panels on the ZR at the factory was generally very good – a legacy of its Honda engineering and production origins. Gaps did widen in the later years as the tooling wore, but they should always be even. The paint shop was one of Longbridge’s prime assets – one of the most advanced in the world having been refitted in the late 1990s in preparation for MINI production, so paint finish, colour and consistency on ZRs should be very good. Wonky panel gaps, signs of ‘adjustment’ to get panels to fit and mismatched colours point to repair work of some kind. Some of the bolder and more ‘out there’ colours available on the ZR (especially the complicated multi-tonal Monogram paints) are less durable and bit more brittle, as well as being much more expensive to rectify any issues, so be especially thorough in checking for rough patches on these cars. The standard paints are good quality.

Engine and transmission

On any K-Series, your primary concern is the fragile head gasket. Look for coffee-coloured fluid on the dipstick or contamination of the coolant. Above all, be sure to take a test run of 20 miles or so, then check for bubbling in the header tank or loss of coolant. The problem can be cured, but it is expensive relative to a car costing £500. It is worth checking the condition of the radiator and any paperwork that comes with the car too – if it has done more than 60,000 miles without replacement, consider budgeting £110-£120 for a new radiator.

K-series cam belts should be changed at different intervals/mileages dependent on engine: 60,000 miles or four years for the ZR160 VVC K-series, but 90,000 miles or six years on the rest. The L-series diesel has a cambelt that should be changed at 84,000 miles or seven years. You are unlikely to see any change out of £400 to have a new belt, water pump and tensioner fitted, rising to at least £600 if you want the peace of mind of having an uprated head gasket fitted at the same time.

An uneven idle on a non-VVC K-series engine could be caused by leaking inlet manifold gasket O-rings which are cheap and easy to fix, or it could be an issue with one of the many electrical connections in the engine management system having become dirty or loose. Fortunately a faulty ECU (which is expensive) is not a common failure point. It could also be down to one or more faulty sensors, which are cheap enough but only when you have correctly diagnosed which one is at fault. Of benefit here is that all cars are EU3 compliant, and so have the standard OBD2 engine diagnostic protocols. This means that a cheap code reader will give a window into the workings of the ECU.

The L-Series is mainly criticised for its relatively rough and crude character, but is generally very robust and reliable. If the engine develops a narrower than expected power band, then this can often be due to the air flow meter going out of calibration, something that is usually only cured with a new one (£25-£95 depending on brand). If the engine smokes badly and has poor performance, then it could have had a cheap-and-nasty ‘tuning box’ added, or it could be suffering from nothing more than an overdue fuel filter replacement.

The R65 gearbox has proved to be a quite reliable unit as long as it is not over-stretched – it was only ever fitted alongside K-series engines up to 1600cc to reflect that it was developed and intended for a small car with a smaller, less powerful engine. The PG1 gearbox is generally reliable too, but a whine in fifth or at idle which does not go away when you step on the clutch means a rebuild or a replacement is imminent. If the whine at idle does go away when you depress the pedal, then it is down to input shaft bearings that need replacing. With high stress conditions it is possible to get a whining at steady speeds that is more often noticed in fourth; this can be the diff bearings complaining. These units can also suffer from seized bushes in the clutch release arm and whilst removal, cleaning and greasing the two bushes (especially the upper) will help provide a long term cure, a replacement from the likes of Brown and Gammons that incorporates a grease nipple makes a lot of sense if you are changing yours.

The CVT gearbox doesn’t have the best of reputations for longevity, but it is better than some people would have you believe. In operation it should be smooth and seamless. Expect some noise from the unit’s oil pump, but poor acceleration, excessive noise or jerky operation suggest expensive repairs. Note also that these ZF gearboxes require special oil and normal CVT oil is potentially damaging, which can be the cause of some of the problems found.

Suspension, steering and brakes

On the suspension, these days knocks and rattles over bumps should send you first of all checking for broken coil springs – ZRs are no worse in this regard than any other car, but potholes and tired or cheap replacement springs are not a happy combination. See also if the balljoints need replacing as the wider wheels of the ZR over the original Rover give these a hard time. Ultimately though, the most common area that will need attention is suspension bushes, and – depending on mileage – dampers.

Brakes are all adequate for road use as standard, but upgrading lower-spec cars with parts from higher up the range is a relatively simple bolt-on affair. Pulsing through the pedal when braking gently at low speed on a car fitted with ABS suggests reluctor ring or sensor failure. Reluctor rings appear to be an integral part of the outer CV joint, but they can be removed and aftermarket replacement rings fitted which are significantly cheaper at under £10 each.

Interior, trim and electrics

Inside the cabin, ZRs were rarely entirely rattle-free from the factory, while time and miles will have done nothing to improve matters. You can spend a lot of time trying to track down and rectify creaks and groans, but success is not guaranteed. Wear to the outer side bolsters of the front seats is also common, but depending on where exactly it has gone, a trimmer should be able to effect a decent repair.

More important is to check that all the electrical fittings are working correctly. Consider fully functioning air conditioning (if fitted) a bonus. Electric windows that don’t work smoothly (or not at all) are not uncommon, and a regulator will cost you from £50 secondhand. Check too that the alarm works properly as the factory system can develop faults. Ideally you want to get two keys that both work on the buttons.

ZRs from mid-2003 (with the round fob that has the MG badge in the middle) changed to the Pektron SCU (security control unit) system that combines all electrical functions bar the engine management into a single ECU and also enhanced security. Unfortunately these SCUs can be a little fragile and see internal faults that stop some electrical functions from working, such as the driver’s electric window, intermittent wipers, horns and so on. These are often on-board relay failures, and these can be replaced by specialists at a much-reduced cost compared with the official repair of a new SCU, which demands new fobs too (see p116 for more).

There is in addition a specific MG ZR weakness in that the SCU is located on the bulkhead behind the heater air intake, and it has the four wiring multiplugs running straight down to the unit. In cars that develop a water leak past the screen (usually following screen replacement), water can track down the wiring and straight into the SCU, quickly causing terminal damage. Any water leak therefore needs urgent sorting, and ideally you should reposition the SCU so the wiring has a bend to prevent water tracking in through the plugs.

MG ZR: our verdict

True British hot hatches are a rare thing, but the ZR is a fine example. Don’t let the dowdy Rover 25 origins put you off – in the MG tradition, humdrum ingredients were turned into a gourmet meal. You do have to beware of tired, under-maintained and thrashed examples, but these are generally simple and rugged cars that do not incur high costs – even the dreaded K-Series head gasket is a largely solved issue today. And the result is a practical modern classic that is immensely rewarded to drive and has the backing of an active and passionate owners’ community.

You can find good ZR105s on the road for as little as £500, but you will probably have to expand the budget to £1500 to bring some of the more powerful models into your orbit. If you want something seriously low miles or perhaps one of the rare Monogram colours, then you could be looking as high as £3500. With a budget of £5000 you’d be able to get hold of a low-mileage and unmolested ZR 105TD or a top-line ZR160.

MG ZR timeline

2001

MG ZR introduced in July, alongside ZS and ZT models. Full range available from the start: ZR105 (103bhp 1.4-litre 16V K-Series engine), ZR120 (117hp 1.8-litre 16V K-Series) and ZR160 (159hp 1.8-litre 16V VVC K-Series), plus ZR TD100 with the 2.0-litre L-Series turbodiesel in two states of tune. ZR120 available with ‘Stepspeed’ CVT with six pre-programmed ratios.

2002

Upgraded diesel model introduced, the ZR TD115 with 115bhp – the same 2.0-litre L-Series engine is used but in a higher state of tune (TD100 model remains available alongside it). ZR105+ model introduced, with a higher level of interior trim and equipment.

2003

Launch of the MG Express – a three-door van derivative of the ZR. Available with the same drivetrain options as the ZR, the Express offers lower weight, better performance and much lower insurance premiums than the standard hatchback version.

2004

Entire MG Rover range is facelifted inside and out. The ZR gets a slatted grille, rear number plate relocates to the bumper and single-unit projector-style headlamps replace original twin-unit design. Interior updated with ‘Technical Grey’ dashboard and rotary air vents. Trophy and Trophy SE trim levels introduced.

2005

MG ZR production ends in April when MG Rover enters administration. A total of 74,136 ZRs have been built, plus just over 300 Express vans.