The Ford Anglia and Hillman Imp took different journeys to a similar destination, but which makes the best classic buy?

Despite the detail differences, today’s small city cars are almost universally variations on the same theme; squashed-looking five-door hatches with three-pot engines, many of which are built on the same platform. Rewind back to the late 1950s though, and things were very different. BMC may have grabbed the headlines with its front-wheel-drive Mini, but Ford and Rootes were busy going their own ways in delivering frugal family transport for the masses. Enter the Ford Anglia 105E in 1959, and some four years later, the Hillman Imp.

Both cars are often lumped together as mere Mini alternatives, but aside from both having American-influenced styling, they went about solving the small car conundrum in very different ways. Though the Anglia ushered in plenty of fresh features, it maintained a conventional front-engined, rear-drive layout. Rootes, on the other hand went against the trends of the era by slotting in an all-alloy OHC engine driving the rear wheels. Ford’s approach would prove to be the better seller when the cars were new, but which makes the better classic purchase today?

Ford Anglia 105E

Launched in September 1959, the Anglia 105E has established itself as one of the most recognisable classics of all time. With its transatlantic styling and controversial reverse raked rear window, it was noticeably different from its plainer 100E predecessor, and a world apart from the archaic ‘sit-up-and-beg’ Popular that could trace its roots back to before the War.

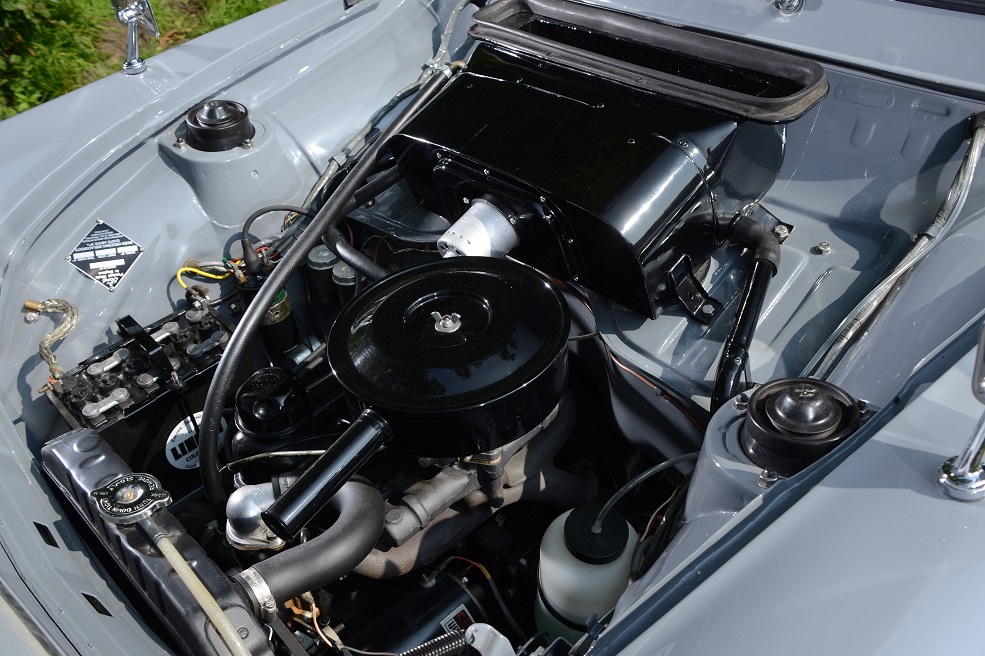

Another headline was the fitment of a brand-new 997cc motor subsequently known as the pre-crossflow Kent unit, rather than the side-valve used for the 100E. Of an oversquare design, the new unit won praise for its smoothness at high revs and was further helped by the Ford Anglia 105E becoming the first British Ford to get a four-speed gearbox. MacPherson strut front suspension carried over from the 100E ensured the Anglia rode and handled pretty well, and the steering was nice and light too.

The Anglia 105E was an immediate hit. Initially you could specify the car in sparse Standard trim with minimal brightwork, or in Deluxe guise with a full-width chrome grille instead of a plainer narrow item, plus such goodies as a temperature gauge, carpets, a glovebox lid and a passenger sun visor. The range continued unchanged until June 1961, when the 5cwt and 7cwt Vans were introduced, followed by the Estate version in the September.

However, it was the 1962 introduction of the Super, designated 123E, that really took the Anglia to another level. As well as a larger 1198cc engine, it had synchromesh on all four gears and bigger drum brakes. It was also more visually appealing, thanks to two-tone paint, a side stripe, extra chrome trim and a plusher interior complete with a standard heater.

The Ford Anglia enjoyed competition success too – most notably winning the 1966 British Saloon Car Championship in the hands of John Fitzpatrick. That year, two specials were released based on both the Deluxe and Super models, available in special Venetian Gold or Blue Mink metallic paint finishes. Some 250 were sold in blue, and 500 in gold. In truth though, changes to the Anglia were minimal in its eight-year life, and when UK production drew to a close in 1967, it was cheaper than in 1959.

By the end, almost 1.3m saloons, estates and commercials had been built. Its Escort replacement was a monumental success, but the Anglia remained at the forefront of popular culture and still has many fans. Younger folk will recognise it as the flying car in the Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets film, but there’s also Roland Rat’s Ford Anglia and the flame-adorned example driven by Vyvyan in The Young Ones, not to forget the wide-wheeled the ‘Carlos Fandango’ Anglia in the Panama Cigars ads.

Characterful and accessible, the Anglia was a popular choice for leagues of first-time drivers and was also a popular choice for customisers – think jacked-up suspension, flames, mag wheels and the like. The 997cc Kent engine is more durable than the 1.2-litre alternative, which can be a bit of a bottom-end rumbler, but both are strong units. Nevertheless, a massive range of engines and gearboxes have been craned in over the years, from simple larger-capacity Kent motors to Pintos and even V6 units – few small cars are as versatile as the Anglia in this respect.

The trade-off is that good original cars have become scarce, while rust has killed many others. The floor pans, sills, rear spring hangers and jacking points are all grot spots, as are the inner wings and the strut tops. Front wings are a particular issue; new steel ones are not cheap and were unavailable for many years, hence fibreglass versions have long been common.

Find one that isn’t hiding horrors though, and you’ll have a practical, useable classic. The performance is sprightly enough for a car of its age, especially the 123E, while the handling is safe and predictable enough for it to be thrown around with gusto. And while its design dated quickly at the time, the Ford Anglia has stood the test of time as a classic choice.

Hillman Imp

The Hillman Imp was truly a clean sheet design. As well as ushering in a host of pioneering new features, it was even built in a completely new factory – the purpose-built Linwood plant in Scotland.

With development extending back to the mid-1950s, Rootes was committed to the car’s planned rear-engined layout, which would be a first for a mass-produced British car. And even though the Mini rendered such thinking old hat by the time the Imp made its bow in 1963, there was still innovation aplenty. As Rootes didn’t produce an engine small enough, it approached Coventry Climax, which developed its aluminium race motor into a rev-happy 875cc road unit that belied its small capacity. With an overhead camshaft layout and its light weight, it was years ahead of rival manufacturers’ efforts, while the use of a bespoke full-synchromesh transaxle resulted in a superb gearchange.

Other novel features included a lift-up rear screen to boost access to the folding rear seats, an automatic choke, a pneumatic throttle, a diaphragm-spung clutch and semi-trailing arm independent rear suspension. It was all cloaked in a body that drew more than a little bit of inspiration from a contemporary Chevrolet Corvair, meaning it could boast American styling like the Anglia but in a more up-to-date fashion. You also got a neat, ergonomic dashboard that was altogether more modern than the Anglia’s jukebox style affair.

The press was enthusiastic and hopes were high, but the ambitious rush to produce such an advanced car in a new factory before final development had properly concluded had its consequences. The automatic choke and pneumatic throttle became problematic, and the Imp also became notorious for coolant leaks and overheating. Blown cylinder head gaskets were far too common, and the aluminium head could warp if it got too hot.

What’s more, things weren’t helped by Linwood’s poor industrial relations and lack of expertise, so any changes were slow to be implemented. Not only that, but its engine and gearbox were extremely labour intensive. Indeed, in 1964 a beleaguered Rootes Group had to accept its first injection of cash from Chrysler in the USA.

The Imp was initially available in Basic and Deluxe guises, but within 18 months of the launch, Rootes focused on boosting sales via the art of badge-engineering. The luxurious Singer Chamois was first up, with the Commer van next up in 1965. In 1966, the Sunbeam Imp Sport and Singer Chamois Sport arrived, which featured tweaked, twin Stromberg-fed engines to boost power from 39bhp to 51bhp. Coupe versions and the Hillman Husky estate and arrived a year later, closely followed by the sought-after Sunbeam Stiletto, which combined the coupe’s styling with the Sport’s motor and quad lamps up front that also appeared on later Chamois models.

They got more reliable too. The Mk2 model was introduced in 1965 with more conventional choke and throttle set-ups, plus improved front suspension geometry and a tweaked cooling layout. By 1966 the Imp was performing well on the race circuit too, but losses continued, and Chrysler completed a Rootes takeover in 1967.

Though never badged as such, a Mk3 version arrived in 1968 with a new dash and trim, but it soon became clear that any meaningful further development was never going to happen, and models were gradually phased out as the 1970s began. Sadly, its early reliability issues meant buyers lost faith, and the Imp never matched the Mini or Anglia in sales. By the time it was dropped in 1976, 440,000 had been made.

As with the Ford, the Imp can rot in the floors and sills, suspension mounts and front wings, though replacement items are generally a bit cheaper. The same can be said for buying an Imp in the first place – nowadays, you’ll pay around two-thirds the price of an equivalent Anglia. For that, you’ll be getting a car that’s sprightlier than Anglia, has sharper steering and handles better, providing the tyre pressures are correctly set to be much lower at the front. There isn’t as much scope for tuning as with the Anglia, but in standard form, it’s the more engaging drive.

Verdict

Despite the Ford being easier to own, I’m a sucker for the underdog and I’d have to go with the Imp. Not only is it the better car to drive and cheaper, but it’s also more intriguing too – while Ford was great at producing the car that customers wanted, Rootes was attempting to break the mould and break new ground. Even if the gamble didn’t fully pay off, it’s hard not to be impressed by what was a valiant attempt.

I can’t help but also think the Imp is a littler cooler. While the Anglia had Harry Potter, the Imp had Indie frontman Jarvis Cocker as its advocate. And though Cocker rather spoiled it all by having the car ‘pulped’, the notion of the Imp being the alternative, left-field choice has stuck. Find me an Anglia and I’ll find it very hard to resist the urge to modify it, but give me a nice Sunbeam Stiletto and I wouldn’t want to change a thing.