These are some of our favourite all-mechanical classics – free of extraneous electronics and the perfect tonic to modern motoring

Mercedes-Benz W110 200D (1965-1968)

If you want to cut out any sort of essential electricals from your classic – even the points and condenser – you have to go for compression ignition. And you can’t really get a more durable diesel than an old Mercedes.

The W110 ‘Fintail’ was the model which made Mercedes the vehicle of choice for European taxi drivers, virtually all of whom chose the 2.0-litre OM621 four-cylinder indirect injection diesel engine. With a fuel system containing only one moving part, it didn’t have a stop solenoid (instead using a mechanical handle) or even a heater plug light – instead you waited for coil of wire behind a little porthole on the dashboard to start glowing orange as the current flowed.

And if the heater plugs failed you could always coax it into life with a starting handle, a kerosene-soaked rag placed near the air intake and quite a lot of effort!

The W110 was an unusual sight in the UK and few of those were 200Ds. Whether they burn petrol or oil, ‘Fintail’ Mercs make excellent classics these days, but many of those on the market will be imports from Europe (drier southern parts preferred), South Africa or North America.

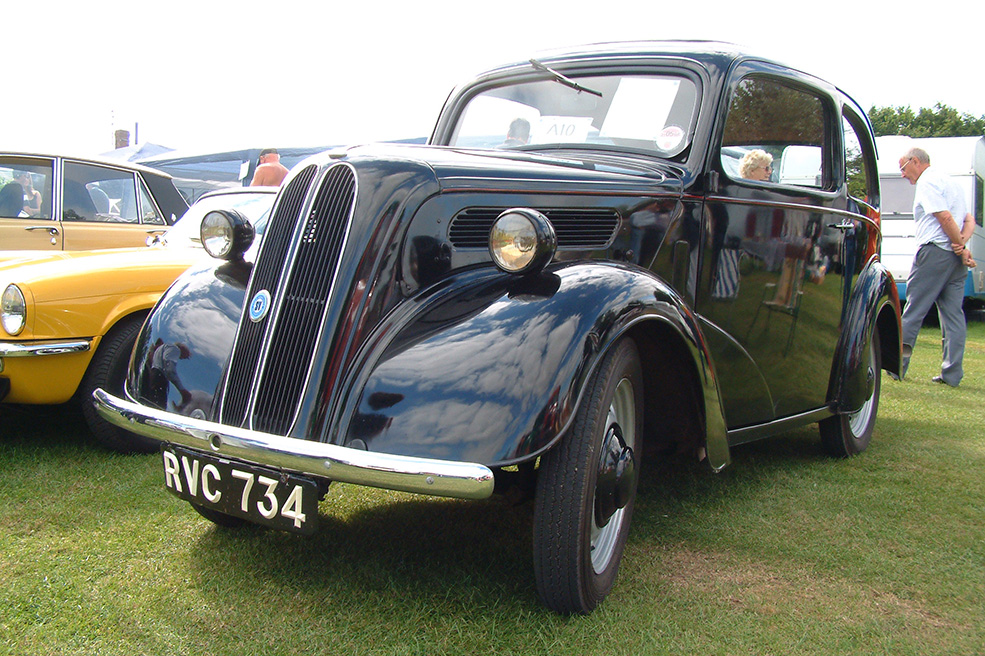

Ford 103E Popular (1953-1959)

Even by the standards of 1950s economy motoring, the 103E (essentially a continuation of the original Ford Model Y from 1932) was basic. When it comes to all-mechanical classics, it doesn’t get much simpler than this.

Intended to provide a low-cost entry to the Ford range, the Popular also filled the vacuum in the used car market that the hiatus of car production during the Second World War and the export drive immediately afterwards had created. There were essentially no five-to-ten year-old used cars on the market, so Ford was building and selling them new!

A thermosyphon-cooled side-valve engine, six-volt electrics, no heater, painted steel bumpers and dashboard, reduced-sized headlamps, a single combined tail/brake lamp and a single vacuum-powered windscreen wiper were what the thrifty 50s motorist got.

But the Popular more than lived up to its name as an economical and hardy little machine that offered the reassurance of a new car and was a step up from the bus or a motorbike and sidecar. It also provided the next generation with cheap wheels when they turned 17 in the following decade.

Range Rover Classic 2-door (1970-1980)

You don’t have to make do with the crudity of a Ford Pop or the limp performance of a 50hp diesel Mercedes to have a classic free of electronic gremlins.

The magnificent original Range Rover is a definitive classic car – historically significant, a masterpiece of styling and design, a legend in its own lifetime and astoundingly capable – whether that’s filling in for a Rover saloon on the road, or following a Land Rover through the rough.

So sure was Rover that the original clientele for the Range Rover would be taking it far off the beaten track that they fitted the 3.5-litre V8’s crank pulley with the dog to accept a starting handle, and put a hole for the handle in the original tubular front bumper. The handle itself formed part of the extensive tool and equipment kit carried in the rear pannier opposite the spare wheel.

So whether it’s an electro-magnetic pulse caused by a solar flare or simply a flat battery, you can always heave an early Range Rover into life.

It wasn’t until 1980 that it was decided that most Range Rovers were not going to ever get far from a jump start and both the handle and the hole in the bumper were deleted.

Still, the Range Rover stands as one of the go-to all-mechanical classics if you fancy a bit of luxury and off-road ability.

Citroen 2CV (1948–1990)

Citroën’s iconic economy car – designed to fit into the French countryside life but loved the world over – is as back-to-basics as they come.

The earliest examples fit the all-mechanical brief the best, but even later 2CV6 models are remarkably simple and perfect for the DIY mechanic to get to grips with. The flat-twin engine is famously robust and –even on later 2CVs produced in 1990 – can start on a handle if needed. If anything goes wrong, parts are easy to source and fit yourself.

Buy a 2CV of any kind and you can expect a driving experience like no other– rifle-bolt gearshift, soft, long-travel suspension and tenacious grip all combine to make the 2CV huge fun to drive. Just don’t expect to get anywhere quickly!

Words: Jack Grover