The Mini and the Citroën 2CV were the only truly entertaining four-seaters at the sharpest end of the market throughout the 1980s. But which is the more complete car?

Words: Sam Skelton Images: Paul Walton

Peoples’ cars in the late 1970s were something of a sorry lot. If you had under £2500 to spend on a car in 1979, your choices would consist of the Lada 1200, the Skoda 120LS, the FSO125p, the Suzuki SC100 and the Fiat 126. In short, small or Soviet – cars too dinky for four, or in the eyes of some, a little too crude.

There were, however, two exceptions – models that had forged themselves reputations over decades of service, and which offered entertaining driving characteristics, room for four and decent luggage space. The A-type Citroëns – specifically the £2072 2CV and the £2290 Dyane – had pretty much had this market sewn up until 1979. But that changed when a new entry level Mini, the City, sneaked in at £2404 – £237 less than the 850 Super DeLuxe model.

Into the 1980s, the battle for the most fun yet fiscally frugal car was a two-horse race between the Citroëns – subsequently amalgamated into a wider 2CV range – and the most basic of Minis. By the end of the decade prices had risen to the extent that a 1989 Mini City would cost £4465 and the popular 2CV Dolly was £3958, but for under £4500, there was still nothing to rival them for their blend of room and entertainment.

The 2CV as a concept can be dated back to the 1930s. Before the Second World War, Citroën Vice President Pierre Boulanger had identified a market for a Toute Petite Voiture – a small car for taking the small family farmer to market with his wares and to Mass with his offspring. Simplicity and reliability were the watchwords, and power wasn’t even a consideration – it had to be repairable with the barest minimum of tools, be easy enough to be driven by a learner or even a woman (this was 1930s France…), and it had to be able to traverse a ploughed field with 50kg of goods on board.

The seats in the original TPV prototypes were hammocks suspended from above, while a water-cooled engine was fitted. They were ready by 1939, but World War 2 meant that the project would be hidden away and put on the back burner until 1945. When Citroën was ready to present the car in 1948, the design parameters had changed – there was now an air cooled engine without gaskets to reduce the number of mating surfaces, interconnected springing, and simpler deckchair style seating that could be removed if necessary. Launched in 1948 at a cost of 225000 francs (The equivalent of £300), priority was given to vets, doctors and farmers. Not in one of those professions? You wouldn’t get your 2CV until 1954 – and that was if you ordered it at the Paris Motor Show.

The first cars had two cylinders and just 375cc – though from 1955 that was raised to 425cc as a cost option. In 1960, this engine became the standard fitment alongside a facelift that saw a new scalloped bonnet design. And that was basically it – the doors became front hinged for 1965 and a rear quarterlight was fitted, but stylistically the last 2CVs were much as the 1960s cars. From 1965 you could order a 602cc engine from the Ami, while in 1970 the 425 became 435cc.

The Ami and Dyane would both come along in the 1960s in attempts to build upon the 2CV formula, but the market wanted the basic model – the 2CV would outlive both courtesy of the early 1970s oil crisis and a revived need in Europe for small and cheap transport. Citroën kept producing them in France until 1988, transferring production to Portugal for the final two years before accepting that it just cost too much to make in a new and primarily automated manufacturing world.

Your first thought as you get behind the wheel of a Deux Chevaux is that it’s almost from a different planet. It’s sparse, but the seats – sprung material over a basic frame – are far more comfortable than the design would have you think. You sit high and upright, but there’s more space than you feel there should be. The handbrake technically sits on the passenger side, while the gear selector sprouts from the dashboard like a bent umbrella handle. There’s room for six footers in the front and back, with plenty of luggage space but no frills. Frankly, opening windows are a luxury, with winders an extravagance that couldn’t be justified – the 2CV always had hinged windows that could be propped open, clipped out of the way or secured shut.

Elsewhere, the door cards are a bit of a Ronseal effort – mere pieces of card with plastic door pulls screwed on. Fresh air ventilation, meanwhile, consists of a flap below the windscreen, though the heater is surprisingly good. There’s no hard roof, because that would have wasted metal – instead, there’s a vinyl hood that appears to be a luxury at first glance. Fold it back, and you just need the basket of eggs to feel like an icon of rural France. We know it’s a cliché, but for a reason.

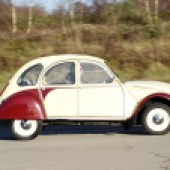

Our test car is one of the very last 2CV Dolly models, a special edition based on the entry Spécial with a limited choice of two-tone paint schemes and Charleston seat covers. This one is finished in the rare and charming Plums and Custard, rather than the typical red and white Strawberries and Cream you expect of a Dolly. And it’s a real one – the Dolly was so popular that dealers would make their own “Dolly Mixture” two-tone models to help ease demand. The interior, as with all Dolly models, is grey.

Turn the key and it cranks slowly at first – a 2CV trait, but they always fire without resorting to the standard starting handle. The gearbox takes some getting used to not only because of the handle but the dog leg first. Twist it to the left and pull back for first, let the clutch in, and the angry insect sound of the flat twin will fill your ears as you lurch away. Second and third are on the same plane in the box, all the better for rural hills and farmyards alike.

A 2CV is one of those experiences that you shouldn’t have to explain – because nobody will understand until they experience it. The steering is very well weighted and direct, even if from outside corners look perilous through the frankly nautical levels of lean. That’s a by-product of the soft suspension though, which makes unmade roads a pleasure– and if you know how, you can make the lean work for you in the bends. Where every road has a rut or a pothole, cars like this make a mockery of the modern trend toward “sports” suspension – you can go far faster in the 2CV. And better still, that’s how they want to be driven.

Drive a 2CV slowly and you probably won’t enjoy it much – it’s a sparse and slow tin box. But recognise that the joy is in coaxing every last bit out of that tiny engine and conserving hard-won speed in the bends, and you will struggle to find a sports car that offers a greater level of basic driving pleasure than the humble Tin Snail. The gearbox might seem odd at first but it’s a gem, with well-chosen ratios and a design that makes crunching almost impossible however quickly you shift. When you’ve finished having fun, there’s space for a sheep or two in the back, a couple of hay bales, or – if you believe the Antiques Roadshow – a grandfather clock – there isn’t one on the dashboard, after all. But the main point is that it’s the ideal classic for those needing to transport a family.

The best bit about the car though is the people who own them. 2CV people are happy, friendly, and welcoming – and the club atmosphere is as good a reason as any to take the plunge. There are few more rewarding ownership experiences than a 2CV. With that said, fans of the car we’re pitting it against might think that their ownership experience is just as rewarding, if not more so.

The Mini is one of those cars that needs no introduction. It was Leonard Lord who set the wheels in motion, tasking Alec Issigonis to make a genuinely small car that would put an end to the bubble cars that had risen in prominence since the fuel rationing sparked by the Suez Crisis.

Strictly speaking, the small car project had existed before the Suez Crisis, but it was accelerated by the need to produce fuel efficient cars and by Lord’s hatred of the microcar. It had to seat four with some provision for luggage in as little space as was possible. After short dabbles with a two-cylinder version, Issigonis took the A-series used in the Morris Minor and Austin A35, and turned it sideways across the car. This measure, along with a gearbox in the sump, meant that the engine and gearbox could be packaged for front wheel drive in just 18” of length – leaving the rest for passengers. And at just 10 feet and a quarter inch in length, the Mini was a packaging marvel. Inside, hollowed out doors with sliding windows maximised carrying space and elbow room, there was space under the seats for storage, and while a large boot was never Issigonis’s priority, the Mini could nonetheless house a surprising amount.

In 1959 the Austin Seven and Morris Mini-Minor were launched, and over time the two ranges would resolve into one – the Mini. Over time there were many variations – estates, vans, pick-ups, Riley and Wolseley luxury derivatives and the 70s-tastic Clubman, to say nothing of the powerful Cooper. But through it all, the basic Mini endured – going from 848cc to 998cc in 1980, and then to 1275 in 1993. Mini production would finally end in 2000.

And the car we have on test today is one of the last of the original breed – a 1979 Mini City, finished in Sandglow. By September 1980, even this car would have a 998cc engine from the new A+ range, despite its entry level position. Brochures for the City boasted of houndstooth trim and side stripes, black-finished bumpers, grille and drip rail, plus a ticket holder in the sole sun visor. Enough for husbands to leave notes to their wives apologising for borrowing the Mini once again, if the advertising copy is to be believed. Owned by Lizzie Horne, it’s one of the nicest Minis left today in standard condition – and would look perfect in the driveway of a late ’70s Barratt Home alongside a nice Marina or Princess.

Inside, the City is plusher than a Mini of two decades earlier, but not by much. You get black PVC and houndstooth cloth seats, proper door cards, but there’s still a full width shelf with a speedo set into its centre rather than a more comprehensive dash panel. But compared to a 1959 Mini, even the winding windows on this car seem like a decadent touch. Like the 2CV, the floor of the City is covered in a rubberised matting – carpet came at a cost, even in the Mini. The seats with fixed backs make for an interesting driving position if you’re over six feet tall, but that’s not to say it feels cramped.

Pull away, and it’s a far faster machine than the Tin Snail – more of a tin hare. It almost feels criminal that 848cc can make a car feel this fast, and John Cooper’s assertion that the first Mini he drove felt just like a sports car is more plausible by the second. The traditional BL box in sump whine adds to the raw sensation – it’s like you’re in a grown up go kart that has broken free of the track for which it was intended, and the well-spaced gears are a pleasure to shift via the rod-change gearlever – the magic wand of the early cars having long departed.

On a personal note it’s some six years since I last drove a Mini properly, and I don’t remember that Mayfair auto being anything like this entertaining. Moreover, I don’t even remember the 970 S I drove in 2014 being this entertaining. This humble little 850 City is exactly what the Mini was always meant to be, and proves that diluting design purity always results in a compromise. This car is – in a single word – fun. And for a car that was this cheap in period, fun alternatives were hard to come by.

Citroën 2CV vs Mini City: our verdict

These two cars prove without a shadow of doubt that an entry level car at an entry level price doesn’t have to be grim. Both combine parsimonious habits with hilarious handling and as classics both are among the easiest ownership prospects out there. Much, indeed, as when they were new.

And if we’re honest, you’re a winner if you buy either car. Both come with their own close-knit yet friendly enthusiast scene, both can be used regularly and neither will break the bank. The Mini experience is about as fun as it gets. But for us, the Citroën 2CV experience is a more charming one. It’s a bigger car, and it makes use of that space well – four six footers could go some distance in the Deux Chevaux without issue, and the removable seats add an air of additional practicality. In a Britain whose roads are pockmarked by potholes the softer suspension is a boon, and the lean in the bends is frankly hilarious.

The Mini is almost certainly the better sporty drive – it has no right to feel as fast as it does, and this particular example exudes charm from every panel gap, but given the choice I’d be taking the 2CV home.