The recent surge in electric classics has mainly been a high-end business fuelled by manufacturer-backed conversions. We find a much more down-to-earth approach in this electric Morris Minor.

Admittedly you do find yourself in some unlikely situations doing this job but on the scale of ‘things you never thought you’d do’ trundling round Parliament Square in an eerily silent yet surprisingly spritely 1953 electric Morris Minor to the soundtrack of Cypress Hill’s Insane In The Brain ranks pretty highly.

Despite the slightly surreal nature of the experience though, the idea couldn’t be more sensible and when London Electric Cars’ Matthew Quitter tells me the cost of putting it together it seems like a no-brainer.

LEC’s Morris isn’t the first electric classic of course, but it is the first really usable concept we’ve come across here in the UK, aimed at people who genuinely want to use the cars in converted form.

Interest in electric-powered classics has traditionally been strong in environmentally aware California and only in the last few years has it become more popular in Europe. The highest profile is enjoyed by Jaguar’s own E-Type Zero as featured courtesy of some high-level product placement in the last Royal Wedding, but although it’s an impressively neat piece of engineering, it’s hardly an everyday car: you’re looking at £300,000 to get behind the wheel, which doesn’t encourage you to leave it in the station car park every day.

Elsewhere, Aston Martin has similarly jumped on the high-end bandwagon with a converted DB6, while MINI has built a one-off classic Mini with electric propulsion as a novelty which isn’t even on general sale. A similar Mini will be offered to public sale by Swindon-based Swind but again is a costly proposition at around £80,000 as are the handful of other companies converting cars – many of which curiously never seem to be quite ready to test.

This 1953 Minor on the other hand is very much ready and willing, having been used on a daily basis around the Capital by Matthew for some time.

Key to its appeal is the pragmatic approach taken by London Electric. For a start, the firm is happy to use second-hand parts to create the conversion and in general has found the tried-and-tested Nissan Leaf to offer the components required.

Rather unsurprisingly, it seems that a salvage industry which is still dragging itself out of the oily mud of the traditional breaker’s yard still doesn’t know quite what to do with a crashed electric car. After all, batteries, controllers and motors don’t wear out in the same way as internal combustion engines or geared transmissions, meaning there’s not much of a market for used parts, so when an enterprising conversion company comes knocking then you’re only too keen to get the parts off your hands.

The Leaf also has the advantage of using componentry designed to fit into a medium-sized platform, making the task of installing them into the average classic car that much easier. The batteries for example are a modular design, meaning that individual cells can be assembled into different sized packs to suit each car. Simple threaded bars and suitable end plates are all that’s required to create a bespoke unit to suit each installation. It also means that in cases where space is tight, the batteries can be distributed around the car in multiple units.

The Leaf also uses relatively traditional lithium manganese oxide battery chemistry, meaning the units aren’t quite so unstable as, for example the higher-density Nickel Cobalt Aluminium chemistry used by Tesla which requires the batteries to be effectively armoured for safety. This in turn adds a lot of weight and requires more complex battery cooling, which is avoided by using the Nissan componentry.

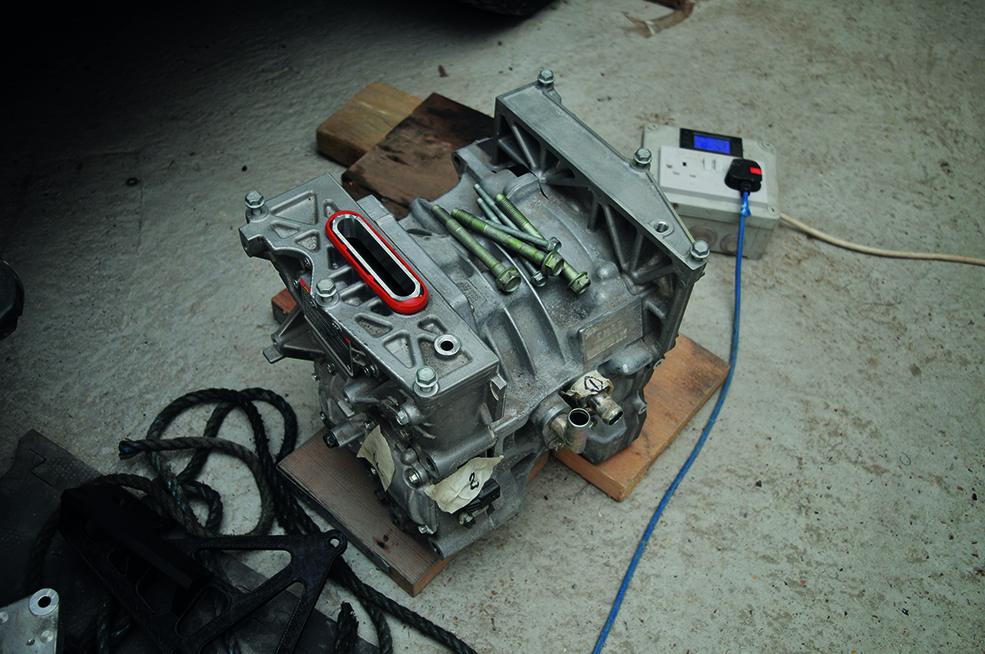

The LEC Minor also retains the original car’s four-speed manual transmission, which further keeps the cost of conversion down and also retains more of the car’s original character. You don’t need to stir the gearlever as frequently as the petrol-powered Minor and the clutch doesn’t see much action but the car still needs to be driven in the conventional way.

Looking around the Morris, from the outside you’d be hard pressed to tell that it’s been converted. Indeed, a look through the window gives you no further clues either, since electronic displays are hidden inside the glovebox and the dashboard remains standard.

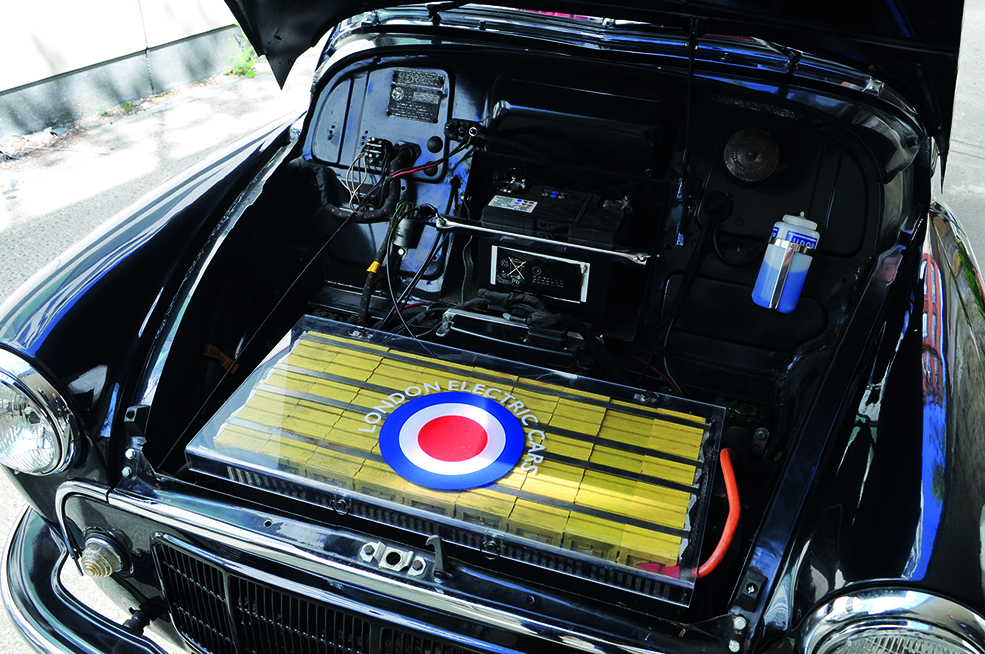

Under the bonnet though, things are very different, but the car remains essentially standard, LEC’s philosophy being to avoid cutting and welding.

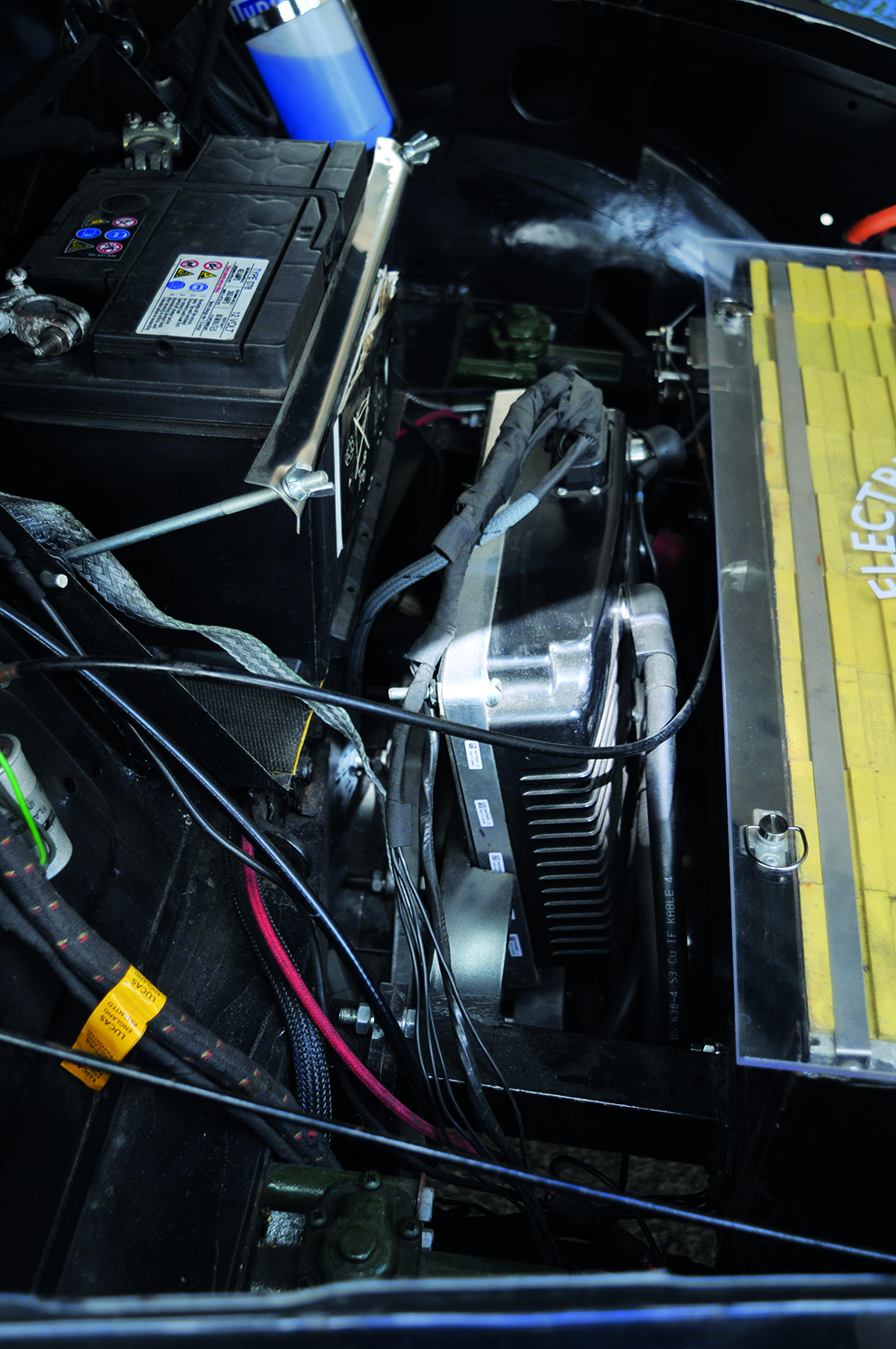

Issigonis’s original idea of using a flat-four engine provided an engine bay which was more than generous for the A-Series four-pot and provides ample space for the electronics. The view is dominated by the battery pack – in this case a total of 25 165Ah Thundersky Prismatic cells taken from an older electric conversion – and tucked behind it is the Curtis 1230 controller, while largely hidden from view is the motor itself which bolts up to the original gearbox bellhousing via an adapter plate.

The supporting frame for the batteries is welded to the bodywork in this car, but the Minor installation has since been refined to the point where existing damper mounting bolts can be used.

Open the boot and where the spare wheel usually lives under the floor is another battery box, with the coiled charging wire another giveaway that this isn’t your usual Moggy.

I found the presence of the standard 12-volt car battery an amusing sight under the bonnet but this is explained by the traction motor running at 96 volts. Clearly, the lights, wipers and all the rest still rely on the traditional 12 volts, hence the use of the original battery which is charged not by an alternator but by a DC to DC converter which steps down the traction battery voltage, while a simple fusebox replaces the original voltage regulator. This has the advantage that if required the majority of the car’s original wiring loom can be retained.

The motor used in this car is a 30hp unit offering 100 lbf.ft torque which in theory gives the car a range of 40 miles and a top speed of 50mph. Since the car is very much intended as an urban runabout, this is ample and as Matthew points out, in real-world daily use around London it only needs charging once a week. The Minor’s light weight helps here: a 24Kw set-up would give a 100-mile range in a Mini, 80 miles in something like the Minor or 40 miles in a Land Rover.

So what’s it like on the road? Both comfortably familiar and startlingly different is the answer. Although the standard manual box and clutch is retained, the electric motor isn’t rotating at a standstill, so there’s no need to use the clutch when pulling away. When doing a three-point turn for example or backing out of a driveway, the procedure is simply to switch the car on via the original dashboard ignition key switch, select first or reverse without even pressing the clutch pedal and then just ease on the throttle, at which point the car glides away.

From a standing start, it gathers speed impressively well thanks to the electric motor’s characteristic of providing maximum torque at zero rpm and this makes it easily able to mix it with the most modern of city traffic. The high torque of the motor – after all, it’s twice what the original engine offered – renders first gear effectively redundant and for most city driving Matthew reports that the car is quite happy in second. On faster routes the clutch is employed just as in a petrol car to change up, at which point third can also be skipped entirely and the direct-drive fourth used. This also makes the car much quieter from inside, since the notoriously rackety second gear in the Morris box becomes prominent when there’s no engine to mask it.

In fourth the Minor is quite happy to spin up to 55mph or thereabouts, but since this Moggy is of 1953 vintage and – electric drive apart – all-original, its drum brakes and lack of seatbelts mean this is something for the brave. And speaking of brakes, an adjustable regenerative affect is programmed into the system, meaning that lifting off the throttle has a noticeable braking effect. As with many current electric cars, with enough practice you can avoid touching the brake pedal entirely – the benefit meaning the increase in range which can be as much as 10 per cent.

Top speed isn’t what this Morris is about, anyway – it’s a very usable city car with all the charm of the original which really can be used on a daily basis with as much convenience as a Nissan Leaf, Renault Zoe or Tesla. And, it must be said, far more style than any of them.

And cost? Matthew reckons that including the cost of the parts, a conversion like this can be achieved for under £20,000 in most cases, which is a world away from the other options out there.

Interest in conversions like this is growing fast and back at the workshop, we find another completed project in the shape of a Series 2 Land Rover. Being a heavier vehicle altogether, this requires more batteries, a heftier motor and a cooling system for the electronics, but of course the trade-off is that there’s more space to accommodate the batteries too. One box under the bonnet is complemented by a pair hidden underneath and one under the rear, while like the Minor, the conversion also retains the original transmission – including the low-range transfer box and four-wheel drive.

The philosophy at LEC is to retain as much familiarity as possible, which is achieved by attending to detail work like retaining the original throttle pedal linkage – which obviously now attaches to an electronic controller switch rather than the butterfly of an SU carb but which as a result retains the same pedal feel, making it familiar to drive.

The light-duty Morris installation gets away without cooling, but the heftier Land Rover installation demands more of its electronics and so a cooling system is required. This is achieved using largely computer cooling technology, with a reservoir of fluid which is pumped through a radiator cooled by electric fans. Like an automotive cooling system in miniature, it’s the type of setup you’d find used on a really heavy duty PC.

Alongside the Land Rover, candidates lining up for conversion include a Volkswagen Karmann Ghia and also a Lancia Beta HPE, while much thought on the day of our visit was going into a conversion of a classic Mini. It’s no surprise to learn that the primary challenge in this case was finding space to install the batteries neatly, but the flexible nature of LEC’s approach meant that all the nooks and crannies could be filled usefully.

It’s no surprise to learn that a car of the Morris’s vintage is easier to convert than more modern classics with no power brakes, no power steering and no ABS to consider. Not that these issues are impossible to solve: a vacuum pump can be employed to power a brake servo, while electric power steering is commonplace these days or an electric pump can be used to supply the original hydraulic set-up.

As I strolled back to the Underground past a line of hybrid Toyotas, they suddenly seemed clumsy and old-fashioned compared to the 66-year old Morris I’d just stepped out of which seemed perfectly suited to city life. Ordinarily, I’d be opposed to the idea of radically re-engineering a ’50s Minor but somehow the LEC conversion is so much more elegant than any of the usual engine swaps Minors are subjected to. Yes, you could easily put the car back to standard of course, but… you know what? After just five minutes you really wouldn’t want to.

Electric traction

It’s easy to think of electric cars as the epitome of modern high-tech, but once you chat to people involved in the business, perhaps the biggest shock is how very simple they are. As Matthew points out, an electric car is still very much like the remote control Tamiya cars you might have built up in the past and the essential ingredients are the same: a battery pack, a speed controller and a motor.

Whereas your Lunchbox or Sand Scorcher used the remote control servo to operate the speed controller, in the electric car it’s your foot on the throttle pedal doing the same thing. There are a few differences, granted: the battery pack’s DC power is converted to AC by an inverter, the use of an AC motor meaning it can be a brushless design for quieter, more reliable and more efficient operation.

London Electric Cars

It’s no surprise to hear that before establishing London Electric Cars, Matthew enjoyed a career in software, but a love of classic cars proved to him just how cost-effective they can be when living in Central London. Amusingly, the time spent working in music production studios proved to be ideal experience for dealing with electric propulsion, since the science of pulse width modulation as used in synthesizer technology is also used in electric motor control.

Casting around for a new venture, he saw the light after getting complaints from his girlfriend about the exhaust fumes from his Spitfire while sitting at traffic lights. The idea of converting classic cars to electric drive was born and he hasn’t looked back.

Ironically, the biggest abuse – good-natured though it is – comes not from the classic car purists but from electric car pioneers like the Battery Vehicle Society. With the rise to prominence of Tesla and its rivals, companies like LEC are getting the praise while the BEV people have endured the years of ridicule. And the Spitfire? Matthew still has the car, but ironically, it still runs on petrol power. For how long, we wonder.

Find out more at http://londonelectriccars.com/