The last car to be developed by an independent Daimler company, the adventurous Dart ended its life with the name SP250 under Jaguar ownership.

The Daimler Dart – or SP250 as it’s also known for reasons we’ll come to in a moment – is one of those cars which on paper sounds like a winner but which in reality proved to be less than successful.

The reasons for this were a combination of the unfortunate circumstances around its development and also some engineering issues which arose partly as a result of this.

Despite endlessly being confused with the German firm Daimler-Benz, the Daimler brand was one of Britain’s oldest established car marques, established in Coventry back in 1897 and in its early years famed for technical innovation.

By the 1920s though, financial difficulties had forced it to become part of BSA, with the outdated style of its cars causing it to temporarily retreat into commercial and military manufacture until the resumption of car production with the Daimler 15 in 1932. The firm did well in WW2 with military contracts including armoured cars, tanks and aero engines which saw it expand into several ‘shadow’ factories in the Coventry area.

Postwar times saw the ostentatious Daimler range somewhat out of step with the newly austere times though and when a double Purchase Tax was introduced in 1947 on cars over £1000, things were looking bad – the outlook becoming bleaker when the British monarchy switched its allegiance from Daimler to Rolls-Royce in 1950.

As a result the firm was acquired by BSA in 1951, which already owned the Ariel and Triumph motorcycle brands, a move which would later be significant in the creation of the Dart.

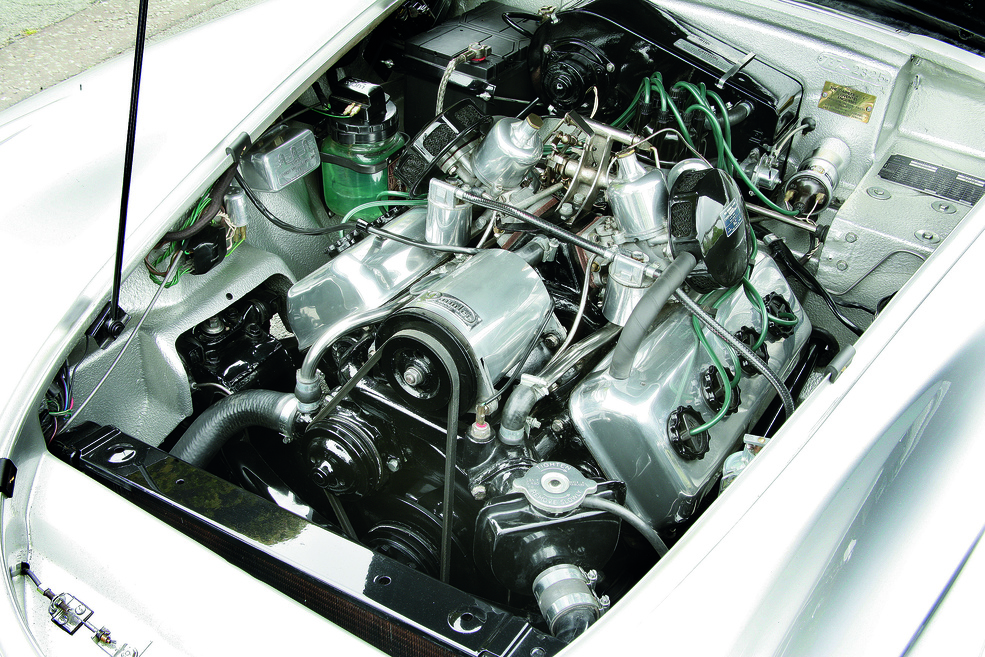

The acquisition saw ex-Triumph engineer Edward Turner installed as managing director, who designed a hemi-head V8 unit for Daimler in both 2.5 and 4.5-litre flavours.

With sales still moribund, Daimler management was well aware of the need to produce a range of smaller, more affordable models and was also aware of the popularity of British sports cars, especially in the USA.

The plan to revive the brand included a car to tackle the two-seat roadster market but with a unique twist: using Turner’s V8 engine would make a Daimler roadster unique in a market characterised by four and six-cylinder engines.

The development budget was tiny but Daimler managed to bring its new car to market by using a separate chassis and a bodyshell made from fibreglass rather than steel.

Not only was the fibreglass body lighter than a steel shell but it was also cheaper to produce (about a tenth of the cost), although the fish-faced styling was very much of the love-it-or-hate-it school. Daimler also had experience working with fibreglass courtesy of its bus-making activities.

The car was launched as the Daimler Dart in 1959 at the New York motor show, an unfortunate location since it saw the new car come to the notice of Chrysler. The US firm had already trademarked the Dart badge for its Dodge models and so a hasty renaming was performed with the car then known as the SP250.

The naming dispute wasn’t the only problem for the Dart. The chassis was almost a straight copy of the Triumph TR3’s simple ladder design but with added bracing for the larger engine and fibreglass body and it was here that problems arose. The SP250 was quick, with the V8 making it good for 120 mph but the chassis of the early cars simply wasn’t up to the job, with owners reporting that doors could even fly open under spirited driving.

Daimler though, had bigger problems to contend with. Its new range of cars had failed to stem the decline in sales which coincided with a rash of expansion across town in Coventry at Jaguar where William Lyons was running out of production capacity at Browns Lane, the local government not permitting further development in the Allesley area of the city.

Lyons would have known the basics of the Daimler finances and would have been aware that the time was ripe for a takeover offer, which was duly made in 1960. The prize in business terms wasn’t the under-performing car division but the factory space nearby in Radford, totalling a million square feet which was just what Jaguar needed and which doubled its production capacity as well as adding another 1672 employees to the workforce.

In Lyons’ typical autocratic style, the takeover was completed as something of a snap decision and even Jaguar’s main board members were unaware of it until it was announced in the press. As Lyons’ official biography relates, Jaguar’s Vice-Chairman William Heynes heard the announcement on the radio at 7am while shaving. The deal between Sangster and Lyons saw Jaguar agree a figure of £3.1 million for the Daimler firm, plus the difference between Daimler’s assets and liabilities, but the deeper the accountants looked, the more came to light. The Majestic Major V8 was being produced at a rate of just 10 cars a week, while the SP250 was being sold in the USA, but the Daimler name hadn’t even been registered stateside. This left the Coventry Daimler firm vulnerable to possible action by Daimler-Benz, although luckily for all concerned, the German firm hadn’t started trading officially under the Daimler name in the US market. As recounted in Lyons’ biography, apparently Edward Turner had been well aware of this during his tenure as MD but chose to take no action, believing that registering the name may well have woken the sleeping giant.

It was when Jaguar took control that the deficiencies of the SP250’s chassis came to light, with Jaguar engineers discovering that by pressing down on the rear wing the door gap could be opened by up to 8 mm, while the screen pillars could be flexed 25 mm by hand.

To his credit though, Lyons didn’t simply axe the SP250 there and then but allowed the Jaguar engineers to sort out the problems, which they did very effectively.

Fabricated strengtheners were created to combat scuttle shake, including sill beams, a hoop to tie the A-pillars together and reinforcements to the B-pillars, with these known as the B-Spec cars.

The car was further improved in 1963 with a more luxurious interior and these cars are known as the C-Spec model. By this time the SP250 was able to fulfil its potential as a capable sports car, but the damage done to its reputation by the issues with the early cars proved hard to shake off – especially in the crucial but unforgiving US market.

It’s no surprise that production ended in 1964 with a total of just 2654 cars and it was destined to be the last individual Daimler model to be produced by the firm, since future cars would be badge-engineered Jaguars until the brand was dropped by Jaguar in 2009 in the face of trademark competition from the German firm.

As a classic today though, the Dart/SP250 has gathered a loyal following and with most examples on the road having been restored by now, they’re generally sitting on the B-Spec chassis – or at least have received modifications to that end.

With the V8 producing 140 bhp, it’s a quick car by 1950s standards, with the ability to crack 60 mph in 10.2 seconds and power on to 122 mph in manual form. The fibreglass body won’t rot, the chassis is simple to repair if it does start to suffer and the Daimler engine is known to be robust. Its parts-bin make-up means that parts supply is surprisingly good for such a niche model and even trim parts are available from specialists.

All of which explains why values have risen in recent years: the entry ticket to SP250 ownership is around the £10,000 mark but nicer cars are advertised at £20,000 with the best examples going for £38,000 to £40,000.