The Triumph Dolomite mixed the tried-and-tested with a series of firsts to create a premium saloon that really appeals as an affordable classic. Here’s what to look for when buying a Dolly

The Triumph Dolomite endured a rather bizarre gestation, even by British Leyland standards. Its roots began with the front-wheel drive 1300 of 1965, which spawned both the front-wheel drive 1500 and rear-wheel drive Toledo in 1970, and eventually the Dolomite.

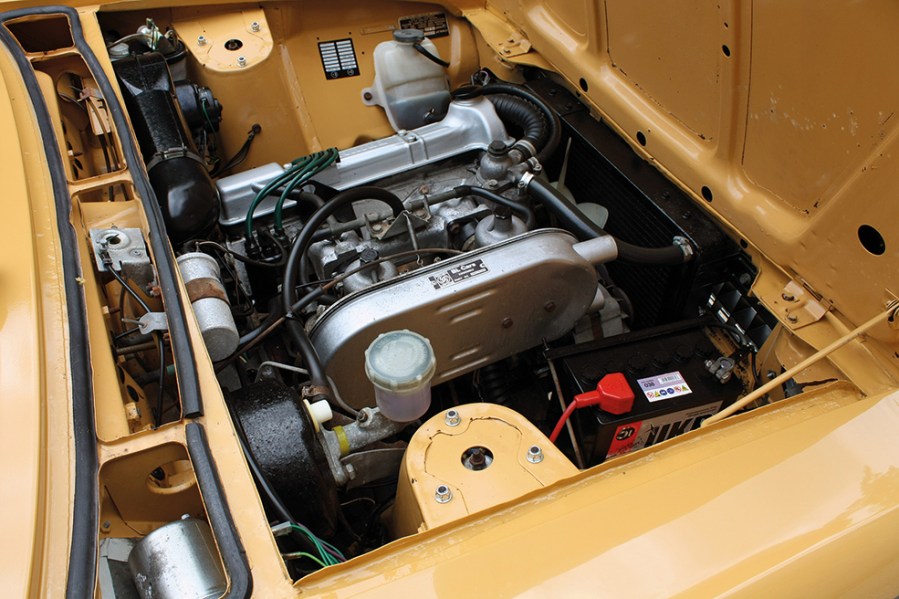

First driven by the press in 1971 but not put on sale until the following year due to a pay dispute with workers, the Triumph Dolomite mixed the Toledo’s rear-wheel drive platform with the 1500’s long-tail bodyshell. It used an 1854cc version of Triumph’s slant-four, overhead camshaft engine, which was funded by Saab and so had first appeared four years earlier as a 1.7-litre unit in the Saab 99.

The 1850 was good for 91bhp, but genuine sports car performance arrived with the Triumph Dolomite Sprint of 1973. Engine capacity was increased to 1998cc and it became the first mainstream production car with a 16-valve head, making it good for an impressive 127bhp. Its stylish GKN wheels also made it the first mass-produced British saloon to wear alloys as standard.

At the same time, the 1500 was replaced by the rear-wheel drive, twin-carb 1500TC, and in 1975, the range was simplified in the wake of BL’s part nationalisation. The Dolomite 1500 replaced the 1500TC, while the 1850 became the more luxurious 1850HL and the 1500 was also made available in HL spec. The Dolomite 1300 was launched too, effectively replacing the Toledo, although this clung on until 1976. The basic square Toledo headlamps remained a fixture, identifying the 1300 and basic 1500 models.

In the main, the Dolomite changed very little during its lifetime, with only minor trim differences and additional standard equipment. By the late 70s it was looking increasingly old-fashioned against newer competition, and with the closure of the Canley factory in 1980, Dolomite production was brought to a conclusion.

Bodywork

Cars built before 1976 seem to be less rust-prone than later siblings, but in any case, the likes of Rimmer Bros and the Triumph Dolomite Club (TDC) have a wide range of repair sections available that give a good indication of the common trouble spots.

On top, the bonnet and wings can rot. GRP wings are available from the club, and so are steel repair sections for the vulnerable lower rear areas. Check around the windscreen for bulges that suggest hidden rot, and check the A posts and all the door bottoms. Again, repair sections for the latter are available from the TDC and they’re £36 each. Rear wheelarches and the lower sections of the rear wings are further trouble spots, with repair panels £42 and £65 respectively per side from the TDC. Also check the area above the rear screen – there are ventilation holes and if corrosion gets a footing, it’s a horrible area to repair. The trailing edge of the boot lid is vulnerable too, and sure to inspect vinyl roofs where fitted for any signs of rust lurking beneath.

Underneath the car, inspect the chassis rails for damage and corrosion, especially where the front subframe attaches to the car. Repair for the rear mounts is tricky and involved, with the area beneath the battery suffering particularly badly thanks to the combined effects of water and battery acid. A replacement rail costs £95 a side from the TDC. The inner wings and suspension turrets also require close examination, and while the bonnet is open, check the rear of the front panel.

The headlamp surrounds can get crusty but can be replaced (£54 per side), and there is an ‘eyebrow’ panel above the headlamps, which is available in GRP. The front panel itself can suffer badly above and below the headlamps, usually worst where it meets the front wings. Repair sections for the latter from the club cost £40 each. Watch also for bubbling around the indicators and along the front valance – the club can supply a new front panel in GRP.

As with any monocoque, sills are absolutely critical for strength. Check along their length and pay attention to where they meet the floorpan and also around the jacking points. New outer sill skins, inner sill repair sections and inner sill diaphragms are thankfully available from the TDC (outer sills are £120 a pair). Floorpans also rot but again can be sourced from the club, as can repair sections for the vulnerable boot floor.

If the owner is happy for you to do so, remove the rear seat backrest as this can reveal hidden corrosion on the inner wheelarches.

Engine and transmission

The Triumph Dolomite 1300 offers a reasonable turn of pace, though is a little noisy at speed due to low gearing. The 1500 is a longer-stroke version of the same engine, but sustained 70mph travelling is pushing the three-bearing crankshaft a bit too far, unless the desirable overdrive is fitted, and big end bearing failures are sadly common. A knock or thump from the lower part of the engine suggests it’s rebuild time. Both these engines will signal bore/piston wear by producing a large amount of blue smoke. The odd burst may just be due to oil seeping past the valves – there are no valve stem seals – but if it occurs all of the time, more work is needed.

The 1850 and Sprint share similar engine structure, using the OHC slant-four engine. Their alloy heads means that regular coolant changes are a good idea, especially as any overheating will cause the head gasket to blow. Otherwise, these engines last well, with over 100,000 easily within reach with frequent oil changes. Both engines can suffer from water pump and/or jackshaft failure, which also causes overheating. The water pump also needs to be properly shimmed when fitted.

In terms of transmission, the 1300/1500 and 1850 share similar gearboxes and rear axles, though they aren’t easily interchangeable. Both initially used a three-rail, Vitesse-derived gearbox until March 1975, which can suffer badly from worn layshaft bearings. That will produce a lot of noise in all gears apart from top. The later single-rail gearbox tends to be tougher but with both, watch out for failing synchromesh causing crunchy gearchanges. Rear axles can get noisy too, especially on the 1850. Cars fitted with overdrive make for a more relaxed motorway experience and are worth searching for, but make sure it’s working properly.

The Triumph Dolomite Sprint has a different gearbox – related to the TR range – and a stronger rear axle, with an optional, and highly desirable, limited-slip differential. Problems tend to be rarer with these stronger parts, but it’s one of many reasons why upgrading an 1850 to Sprint specification isn’t as easy as you might suspect. Rear axles for the Sprint are in short supply, and those with a limited slip differential command a premium. Non-LSD ones are more common.

An automatic transmission was offered on the 1500, 1850 and Sprint. It’s a three-speed Borg Warner unit that rarely gives trouble and should be reasonably smooth-shifting, but is at little at odds with the Sprint’s revvy 16-valve nature.

Suspension, steering and brakes

The steering in a Triumph Dolomite should be precise and almost entirely free of play. If it feels woolly, it might be the steering column bush so see if you can move the steering wheel up and down. Also check the steering column linkage coupling and universal joint. Wheel bearings should have a little end float, so a little play here is entirely correct. Vague steering could be just due to worn steering rack mounts as the rubber degrades. Some opt for polyurethane alternatives which give a tighter feel at the expense of a small amount of refinement. Steering racks themselves are available, but can be fiddly to replace.

The suspension should be clonk free. Watch out for failed dampers, which can cause the car to feel skittish on bumpy corners. Rear springs can sag with age, though the Sprint comes as standard with lower settings. Bush wear can cause a Dolomite to feel loose and floaty at speed. Again, there are polyurethane options but even fresh rubber bushes will make a difference.

Brakes are just about up to the task up to the 1850, but they’re being pushed very hard with the Sprint, so don’t be surprised if upgrades such as ventilated discs and better spec pads have been fitted. Also be sure to check around the master cylinder for leaks and corrosion.

Interior and trim

The Triumph Dolomite was pretty well appointed when new, with plush seating and a wood dashboard. Larger-engined Dolomites and the 1500HL models gained timber door cappings too. Whether cloth or vinyl, the seat material can degrade with time, and carpets can fade and wear through, especially on pre-1976 models. The wood can crack and fade if exposed to sunlight regularly. Look up as well, as the headlining can get grubby or torn. The front parcel shelf can also collapse.

Triumph Dolomite: our verdict

The Dolomite was long in tooth when it was discontinued, and for many years values didn’t justify the cost of a thorough restoration, so numbers dwindled. Now though, it’s an established classic choice. Naturally, it’s the Sprint that delivers the most thrills, but the 1850 in particular also delivers very good performance in a fine-handling, fine-looking car that makes it easy to forget the bodyshell’s front-wheel drive heritage.

The smaller-engined Dolomites should not be overlooked either. The 1300 can be tuned to give a surprising turn of speed and while the 1500 engine certainly has its issues, parts are still plentiful and it’s an easy unit to work on.

For the smaller engine Dolomites, around £3000-£4000 should secure a good 1300, with £3500-£4500 the ballpark for a good 1500 and up to £7000 for the best examples. Auction results suggest that £9000 is the upper limit for well turned-out or restored 1850, but £4000-£5000 is the going rate for a sound, useable car. The Sprint is another matter, with the top values doubling over the past five years. What was a £7000 car in 2017 would now easily fetch £13,000 or more. Low-mileage Sprints in really good condition can sell for £18,000-£20,000 at a dealer, but that’s still cheap compared to a contemporary hot Escort.

Whichever Dolomite you go for, you’ll get something that feels a bit special – a practical small saloon with good club and spares backing that can be enjoyed on a regular basis.