The cheapest cars on offer can be just as interesting as those at the very top. We survey four decades’ worth of bargain basement offerings to the British motorist.

1950s

Once the car market returned to something like normal in the 1950s, Ford took up its usual position as the pre-eminent maker of the cheapest cars around – one established in 1934 by the £100 Model Y Popular. That had been turned into the Ford Anglia in 1939 – essentially a cosmetic facelift on the same chassis and running gear. That in turn had received another restyle, although still with a very 1930s appearance, in 1949 when production restarted.

A genuinely new Ford Anglia didn’t arrive until 1953 with the unitary, square, three-box 100E model. But Ford still had some use to wring out of the old Model Y design and the old Anglia was cost-cut – a single vacuum-operated wiper, no heater, vinyl trim, painted external parts rather than chrome, a steel dash panel and smaller headlamp units – to become the Ford 103E Popular, re-using the name of the budget model of the pre-war years. The 103E did receive the larger 1172cc engine shared with the 100E model, giving it a top speed of 60mph, even if that was a somewhat terrifying prospect given that it retained the Model Y’s transverse leaf springs front and rear and tiny cable-operated brakes.

Whatever its dynamic shortcomings the Ford ‘Pop’ was a commercial success. Priced at £390, or £110 less than the 100E Anglia, it was by far the cheapest new ‘proper’ car on the market. The hiatus of car production during the war years and the restrictions on car sales in the late 1940s had created a dearth of decent-quality used cars in the UK, as the only secondhand cars available were pre-war models then approaching 15 years of age and largely fit for the scrapyard.

No other manufacturer could match Ford’s prices. The nearest was the Standard Eight at £418. With unitary construction, an overhead-valve engine, a four-speed gearbox and hydraulic brakes the Eight was a much more modern car but it was otherwise, if anything, more cripplingly austere than the Ford, being sold with sliding windows and without a radiator grille, hubcaps or a boot lid – luggage had to be shuffled in and out by folding the rear seats. The Austin A30 was £553 and a Series II Morris Minor was £631, or getting on for twice as much as the Pop.

1960s

Going into the 1960s the words ‘Ford Popular’ still conjured up the bargain basement of car buying. The 100E Popular was the cheapest four-seater saloon car on sale, priced at £494. But the real news was what you could buy if you could spring for an extra fiver, as £499 would put you behind the wheel of a basic Morris Mini-Minor or Austin Seven. The new wonder-car from the British Motor Corporation was as advanced as the 100E Popular was archaic. True, the Ford now offered hydraulic brakes and independent front suspension but it was still powered by a pre-war sidevalve engine with a three-speed gearbox and a live rear axle with leaf springs. The Mini, on the other hand, bristled with technology, from its transverse engine driving the front wheels via a sump-mounted transmission to its fully independent rubber cone suspension and tiny ten-inch wheels, to its rack and pinion steering, its two-box shape and its clever and highly spacious interior.

The Mini’s 848cc engine may have been smaller than the Popular’s but it offered a greater top speed (enough to cruise at 70mph – a speed the Ford could barely reach) and swifter acceleration. The Popular was functional, cut-price transport with little thought to driver enjoyment or even practical considerations such as where to put the inevitable oddments of a traveling family. The swift, sharp, perky, grippy Mini was as fun to drive as the Ford was austere.

As is well known, Ford bought a Mini to see how BMC could possibly be selling such a complex, high-tech car for virtually the same as their product and quickly concluded that their competitor was losing £30 on each one sold. BMC always insisted that it made money on the more expensive Deluxe model Minis (£537), which was much more popular than the basic model without a heater, windscreen washers or ashtrays and with rubber floor mats and untrimmed body seams. And of course the later Super (£557) estate (£610), Cooper (£640) and the upmarket Wolseley/Riley variants (£654) of the Mini all had increased profit margins.

At least that was the theory – in reality BMC struggled to build Minis at the volumes needed to make those thin margins add up while technical faults with the early Minis and patchy build quality saw what profit remained obliterated by warranty and recall costs.

The Mini’s character and abilities saw it out-perform the cheaper Ford in the sales charts many times over and was Britain but it was the Blue Oval which reaped the profits while BMC struggled.

1970s

This decade was marked by a large increase in the variety available to cash-strapped motorists. The breaking down of trade barriers following the UK’s entry to the EEC meant that cars from Europe and elsewhere were no longer subject to tariffs, allowing countries with lower cost bases to offer tantalisingly cheap cars which seemed like absolute bargains.

High inflation across the decade makes it hard to directly compare prices but in 1974 the cheapest four-wheeled, four-seat car on the market was the Fiat 126, the 594cc rear-engined angular successor to the delightful ‘Cinquecento’. With 23 horsepower available, the little Fiat couldn’t quite crack the national speed limit, being able to force its way to only 63mph but it cost just £899, did 48mpg and for those that lived in cities, could park nearly anywhere. The basic Mini 850 was still there and still almost certainly losing its maker money even in more cost-efficient Mk3 form priced at £950.

For those willing to venture beyond the Iron Curtain the Moskvitch 412 offered a spacious and sturdy mid-sized saloon with good equipment (halogen headlamps, carpets, a laminated windscreen and a radio) and a 1.5-litre overhead-cam engine good for 90mph for just £985 but build quality was variable, parts could be hard to source, handling was stodgy and the street cred was zero. Similarly lacking in ‘cool factor’ was the Citroen 2CV, newly reintroduced to the UK market at £994. But for all its odd appearance and loping, roly-poly road manners, the 2CV could crack 70mph and do over 45 miles per gallon and had very low service costs.

A famous name in low-cost motoring returned in 1975 when Ford introduced a cut-price, cut-spec version of the new Mk2 Escort under the Popular name, now as the model’s most monastic trim level. With two doors, a 1.1-litre engine, a single wing mirror, circular headlamps, plain chrome wheel trims, rubber floor mats, black vinyl seats, single-speed wipers with washers operated by a foot-operated pump in the driver’s footwell, no radio and no heated rear screen, the Escort Popular was relatively pricey at £1299.

Ford had been as canny as ever, explaining that the price represented 26 weeks’ worth of the average wage of the time, just as the original Model Y Popular’s £100 price had in 1934 and the 100E Popular’s cost had in 1960. Of course Ford failed to mention that the purchasing power of the pound had changed significantly since then, so selling the Escort Popular was very lucrative for its manufacturer.

1980s

A snapshot from the middle of the decade is very illustrative, with some familiar faces and some newcomers. The accolade of Britain’s Cheapest Car changed several times. The Eastern Bloc had the honours early on, with the rear-engined Skoda Estelle priced at just £2547, which was significantly below its nearest competitor, the basic Citroen 2CV Special at £2985.

The Estelle was sold in the UK between 1977 and 1990 but towards the end of the 1980s its price had to be jacked up to remain viable as production volumes and economic troubles in the Czech Republic played against it. But at its peak, and despite being the butt of many terrible jokes, around 10,000 Estelles found UK homes each year, mostly on the back of their low price combined with good mechanical reliability even if the cabin fit and finish could be dire.

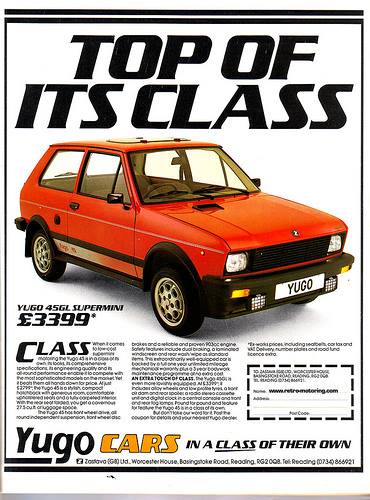

Other cars from the faltering communist economies featured in the lower regions of the price list, with both the Lada Riva 1200 and the Yugo 45 priced at £3099 in 1985. The Lada’s no-nonsense simplicity and ease of maintenance, and its generous equipment levels of its low price,meant it found a pool of willing buyers and in the early part of the decade it briefly reached the status of Britain’s tenth bestselling car.

The Citroen 2CV had a few spells as the least expensive car you could buy, at least when in ultra-basic Special form (no interior light, one wing mirror, no sun visors, cloth seats, no external brightwork and a plain black roof), with a price of just £2985 in 1986, which would help the 2CV reach an all time peak of sales for the UK that year of over 7500 examples. The complicated and (by now) relatively low-volume Mini couldn’t compete, with the most minimalist Mini City priced at £3288.

That left the re-priced Yugo to see out the decade. When the Lada, the Citroen 2CV and the Skoda had all departed, the Yugo in 45A Tempo guise had its price slashed to just £2999 to enjoy a three-year reign as Britain’s least expensive motor. At that time it took the crown from the entry level Ford Fiesta Popular, priced at £3165. Loosely derived from the Fiat 127 supermini, the Yugo had a much more attractive and roomy cabin and decent equipment levels which included intermittent wipers, a locking fuel cap and a rear window wiper.

However, despite a surprisingly good ride, it had handling more reminiscent of the 1950s Ford Popular and build quality varied from atrocious to mediocre, especially once its home nation of Yugoslavia descended into civil war. This halted plans to replace the 45 with the more modern and potentially much better Sana and Yugo sales ended in 1993.