Inspired by military Jeeps and built for farmers, the Land Rover Series I was the car that started it all. Here’s how to buy a great one today

Words: Sam Skelton

After the Second World War, Rover was very much on the back foot. Its staid pre-war saloons weren’t selling and owing to the strict rationing of steel post war the launch of a new car that could sell in volume would be difficult. Rover simply couldn’t get the materials.

That was until engineer Maurice Wilks had a brainwave. He’d been using an ex-US Army Jeep as a beast of burden on his Anglesey farm and felt that there would be a market among farmers for a similar machine. Using an aluminium body and Rover mechanicals, he felt, he could do better. Aluminium was a natural choice; there was a surplus of Birmabright aluminium alloy after the war, and his machine incorporated front and rear power takeoffs to enable it to power belt-driven farm machinery too. Put into production in 1948, there was just one Land Rover – on an 80-inch wheelbase using the 1.6-litre engine from the P3 75 saloon. To enable simplicity of build, the farmers it was aimed at could order it in the following choice of colours: Green.

But Land Rover knew that its simple tractor – where even a roof was a cost option – wouldn’t be for everyone. The following year it launched the Tickford-bodied Station Wagon. This came with leather seats, a heater, an interior light and other options targeted at nicety – a Range Rover 20 years ahead, almost. The problem was that this attracted Purchase Tax as a private car, taking its price into the stratosphere. Just 700 were sold, just 50 of which stayed in the UK.

Land Rover saw the potential for a wider range, though – and on a longer 107-inch chassis introduced for 1953 offered a pickup and – from 1955 – a more utilitarian station wagon with simpler bolt-together bodywork. By then, the engine sat at 2.0-litres, and the smaller standard Land Rover’s chassis had increased to 86 inches. Ahead of the launch of a bespoke 2.0-litre diesel, the wheelbase was lengthened again on all models by two inches and the front crossmember resited. The only model not affected was the 107” Station Wagon, which would never be sold with a diesel engine from the factory.

The diesel, launched in 1957, was the last of the Series I Land Rovers. The next year would the heavily revised and improved Series II model for the Land Rover’s tenth anniversary– but the die had already been cast for the rest of production. By the end of its long life in 1986, the Series III Land Rovers would still sit on 88” and 109” wheelbases, still come with four-cylinder engines in petrol and diesel guise, and still wear square-jawed aluminium bodies.

Bodywork

Woe betides you if you get complacent and think that because a Land Rover is aluminium it can’t corrode. It can, and it will. The chassis and bulkhead of all Series I Land Rovers were made of steel – and while they’re high-quality steel these cars are now nearing 70 years old even at their most recent. Aluminium can also oxidise, resulting in flaking paint, and restoration can be difficult for body shops more used to working with steel. What’s less likely to be an issue than you might expect is galvanic corrosion – yes, we know that Series IIIs and Defenders can suffer and they’re built in a similar way, but the quality of materials used on these early cars is higher and there are far fewer issues than you’d think.

Unless you’re buying a freshly restored show piece, don’t waste your time checking for dents or for unusual panel gaps. These are cars that were designed to do a job rather than to look pretty, and it’s certain that at least one owner will have used any given Series I Landy for the purpose for which it was intended. It won’t be totally straight and it won’t be totally shiny – if it is, the odds are that you’ll be paying too much and not getting the authentic Land Rover experience from your car.

The ones to watch for this are the Tickford models – because of their rarity ad price new they’re more likely to be in good condition but given their scarcity the same rules clearly can’t be applied to them as to the rest of the range. If you’re looking at a Tickford, remember that they’re wooden framed like a Morgan, so check for any rot where possible and ideally have a specialist look over the car for you.

The steel chassis needs careful checking and fortunately on Series Is much of it is visible (skirt panels, valences and other cosmetic panels came along later). The outriggers under the front bulkhead and the rear crossmember under the rear body tub (especially the top surface where mud can collect) are prime rot spots. The front of the main chassis legs where the bumper bolts on can also rust and should be checked for dents or wrinkles indicating that a shunt or other impact has happened at some point – not at all unknown on a working Land Rover but not serious so long as it hasn’t seriously distorted things.

Be especially vigilant of the mounting points for the front of the front springs. The bulkhead goes in the footwells and around the door hinges. The radiator grille panel also needs to be checked. With the exception of that last item (grille panels are not made new and hard to find used, especially for 80-inch models) everything can be repaired fairly easily but it all builds up and if you don’t take stock you can quickly find yourself taking on a full rebuild that you thought ‘only needs patching here and there’.

Engine and transmission

All petrol-powered Land Rover Series I models used developments of the same engine Rover inlet-over-exhaust family, starting with a four-cylinder 1595cc unit in the original 80-inch of 1948. It was expanded to 2.0-litres in 1952 with ‘siamesed’ cylinders and in 1954 a re-jigged version of the same capacity but with ‘spaced’ cylinders was introduced – the late 2.0-litre is considered the most durable engine. At idle when warm the oil pressure can be as little as 10psi, this isn’t an issue. Check that it’s at least 50psi when moving though.

Water loss and emulsion on the oil filler are signs of head gasket failure (quite common on early 2.0-litres) as with anything else; fortunately these cars are easy enough to maintain with minimal tools. Basic oil leaks can be cured, but the rear main oil seal is a difficult one to change and ideally you’d want a car that didn’t leak from here. Check also for moisture on the temperature sensor as another sign. Starter ring gears for the 1.6- and early 2.0-litre are no longer available.

The diesel was also a 2.0-litre unit (2052cc with wet liners and unrelated to the petrol engines in any way) though by now many have been fitted with the later dry-liner 2.25-litre version for increased power and torque. While the substitution of a later engine adversely affects values of the petrol models, this isn’t such an issue for the diesels – which are worth less in the first instance and where originality is less prized. Although many parts are shared between the 2.0- and 2.25-litre diesels, parts unique to the proper 2.0-litre version are rare now, so a rebuild can be very costly. Check for signs of bore wear such as burning oil, high crankcase pressure and piston slap. Running hot, emulsion on the oil cap or dirty coolant may be a head gasket problem or a much more serious cracked head. Black smoke from the exhaust under acceleration and lumpy starting probably just mean the injectors and pump need overhauling, and this is simple and affordable.

If any engine looks like overheating on test walk away, they were designed to be used in low range with minimal airflow and as such should be more than able to maintain temperature in normal use. Blue smoke suggests damage to the rings, as does low compression.

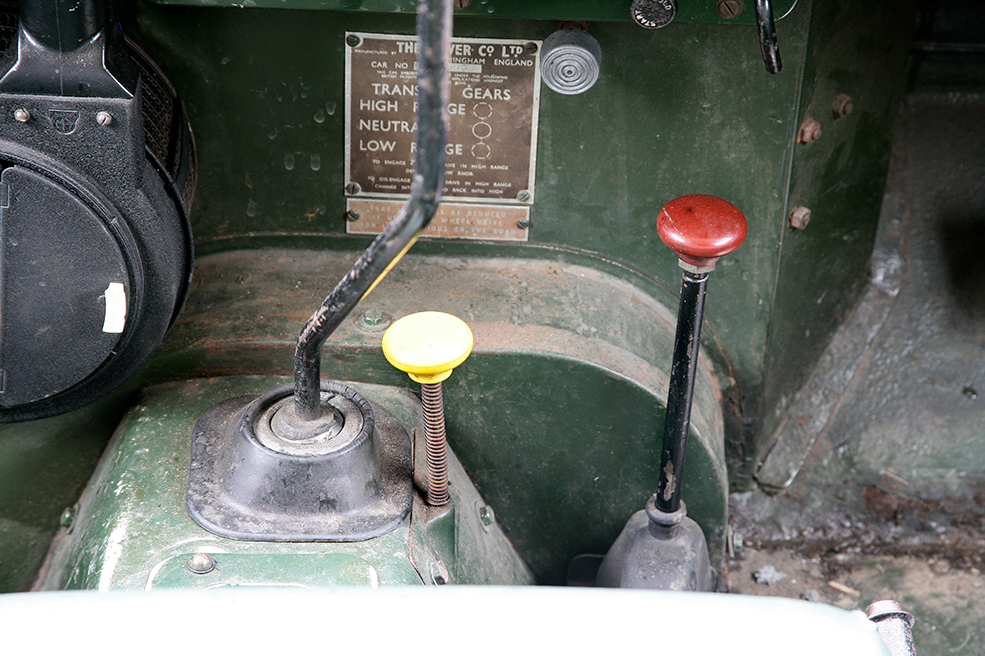

The four-speed gearbox is derived from that used in the Rover P3 road car. It’s a simple ‘box with no real issues provide you can stay on top of the oil level. There’s an old joke about how they only stop leaking when empty, but the truth is that many do leak and that running dry causes more issues than anything else. The two-speed transfer box providing high and low gear ranges via a red-topped lever is common to all Series Is and is very sturdy provided it hasn’t run dry or become full of dirty water. Early 80-inchers had an unusual ‘semi-permanent’ four-wheel drive system where drive to the front axle was engaged under acceleration via a freewheel (as used in Rover saloon cars of the time), which could be locked for better surefootedness by a ring-pull on the transmission tunnel.

From 1950 this was replaced by a more conventional arrangement with a mechanical clutch selecting drive to the front wheels – this was activated automatically when low range was selected with the red-topped lever or by pushing down a new yellow-topped plunger when in high range. Disengaging front drive requires selecting low range, which will make the plunger spring up, then reselecting high range – check it all works as it should. If it doesn’t the cause is usually seizure of the dog clutch or the selector forks through simple lack of use – a bit of 3-in-1 usually sets things right.

Clutches don’t pose any real problems, though it’s worth checking for slipping when you test the car. Check the swivel balls on the front axle – they should be smooth in action, and anything else means specialist attention. Aluminium steering boxes fitted to the earliest models can crack, so check carefully for any sign of damage here.

It’s worth checking chassis numbers, engine numbers, gearbox and back axle numbers with the relevant clubs, in order to verify that the car you’re viewing is original. If anything’s amiss, it will affect the value.

Suspension, steering and brakes

Check for weakness or corrosion on the leaf springs front and rear – the rears in particular can sag with age. On cars with a heavy past of off road use, you might even find cracks or outright breaks in leaves necessitating replacement. On Land Rover Series I models that see minimal use there’s a chance of compacted rust between the leaves of the springs affecting their performance and longevity. The hydraulic dampers do little work on a Series Landy but check that they’re not leaking or entirely defunct.

Check that the brakes work properly, with no undue squealing – they’re drums all-round, and service items are available. It’s possible to upgrade using later parts but we wouldn’t recommend this out of respect for originality.

Check the handbrake – which operates on the propshaft rather than on the wheels. This shouldn’t be tested on a roller system, and as many testers have been known to exempt the handbrake from test it’s worth checking it hasn’t been left neglected over several years. If it won’t hold the car, negotiate a discount ahead of work.

Interior and trim

You can get hold of pretty much any trim you might need for your Land Rover Series I, so this shouldn’t be a major problem. But then, there’s very little trim in the first place. You can get hold of a truck cab, or a canvas hood, or the vinyl trim for the seats – but if you’re keen on absolute originality it can be difficult to get hole of the right switchgear and instruments. These changed during production and it’s often the case that cars have been given updated instruments or period incorrect replacements upon failure. To try and make it perfect will take time.

It should be noted that as with the bodywork, the interior of the Tickford is a wholly different proposition. Their more shapely leather seats can be harder to source, but as they’re covered in leather they should be easily restored by any competent trimmer.

It’s worth using this section to draw attention to the wiring – the looms on these cars will doubtless be damaged through age even if they haven’t been added to, and it’s about time they should be replaced if this hasn’t already been done. Negotiate a discount unless you have proof the job’s been done.

Land Rover Series I: our verdict

It seems alien in a way to think of such a basic and honest beast of burden as a collectible, even classic car. And yet after 74 years the Land Rover is still the standard bearer, the car against which all other classic off-roaders are judged. Unsurprisingly, many change hands within the club, and it can be hard to find good cars on the open market. But the practicality of the Land Rover makes it an option that’s well worth chasing up.

There are two ways to buy an old Landy – you choose to invest in a totally original example, one which will be worth more on the market when you come to sell. Or you buy a car which might have had practical upgrades to maximise your enjoyment, at the cost of investibility.

As enthusiasts, we’d choose a car with as many upgrades as possible in order to get the most joy from it – to us a 2.25-litre engine and uprated brakes, for instance, would make the car a more usable prospect without necessarily damaging its classic provenance. However, there are people who’d rather spend the money and get an original example. These people could expect to spend up to £50,000 securing the best of the best 80-inch vehicles; the 86-inch and 107-inch models are worth about 10 per cent less, as are 88-inch and 109-inch models. If you choose a car that’s not original you could pay up to 20 per cent less and gain an arguably nicer car into the bargain.