The continuously variable transmission (CVT) celebrated 60 years in 2018, but how does it work?

Although Hub van Doorne, one of the original founders of DAF, has been credited with developing the belt-driven variable transmission, the principle for a stepless transmission can be traced back the late 15th century and Leonardo di Vinci. The credit for developing the first operative variable speed transmission goes to Milton Reeves in the late 19th century who produced a version to power a sawmill. Reeves also went on to fit his ‘stepless’ transmission system into a car and Daimler Benz took out the first European patent for an automotive friction-based variable-speed belt transmission in 1886. By the end of the first decade of the 20th century, Zenith Motorcycles were producing a twin-cylinder powered machine equipped with what the company described as the Gradua-Gear system, a much-improved version being used by Rudge-Whitworth in 1912.

During the interwar years several now long-defunct UK and European vehicle manufactures, including Wolverhampton-based Clyno (the name came the company’s patented variable-speed drive for industrial machines using an ‘inclined pulley’) produced small cars incorporating a primitive variable speed transmission and the next big development took place at the end of the 1940s when Charles Denver in the USA patented a design using steel balls aligned by centrifugal force to alter the position of one side of a constantly adjusting cone in which a reinforced V-shaped rubber belt ran. As engine speed increased and decreased, centrifugal force constantly altered the gap between the two sides of the pulley. This caused the belt transferring power to the differential to either speed up or slow down according to how high or low it was riding inside the adjustable pulleys.

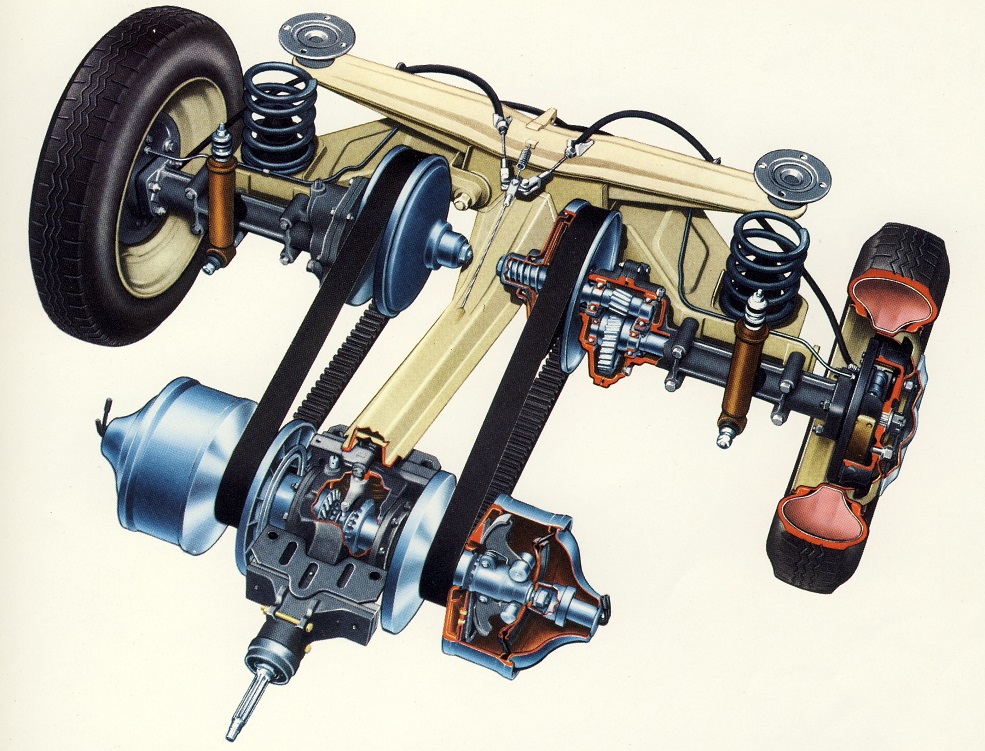

The idea was further developed in the mid-50s in the Netherlands by Hub Van Doorne. The DAF 600 was the first car to utilise Van Doorne’s newfangled transmission and the company marketed the car’s highly advanced clutchless ‘gearbox’ as the Variomatic. In the case of the 600 and a lot of the company’s later models, DAF’s Variomatic transmission featured two sets of pulleys fitted with moveable conical drums driving each rear wheel via a rubber belt. Vacuum from the engine and centrifugal weights inside the primary and secondary drums (or pulleys) caused the ratios to change up and down continuously according to how fast or slow the engine was running and what load it was under. This translated into an infinite number of ‘gears’ between the highest and lowest ratios. One entertaining, or rather dangerous, quirk was how a DAF Variomatic can travel in reverse as fast as it could in forward gear.

DAF continued to develop its Variomatic CVT system right up until the company was taken over by Volvo in the mid-70s. By then the early rubber-belted Variomatic system had given away to a more sophisticated unit featuring clutch-controlled adjustable cones, or pulleys, to aid low-speed driving and help improve economy. Although Volvo used a much-improved version of DAF’s CVT on the automatic 340, later cars used a conventional planetary geared automatic instead.

With the demise of the Volvo 340, variable pulley transmissions were limited to small motorbikes, snowmobiles and farm machinery rather than cars but as car makers started to look at producing more fuel-efficient vehicles, the idea was resurrected.

One of the first utility vehicles to utilise a new breed of steel-belted variable transmission was the 1987 Subaru Justy. The big difference was that this new breed of CVT was now electronically controlled and later that year Ford introduced the CTX-equipped Fiesta while Fiat unveiled a similarly equipped version of the new Uno. Other manufacturers quickly followed suit and more complex steel belted versions of Van Doorn’s original CVT systems quickly went mainstream, with Nissan as the N-CVT and in 1995 Honda introduced its own version, the MultiMatic on automatic versions of the Civic.

Toyota marketed their CVT system as the Multi Drive and in 2000 Audi offered a chain-driven Multitronic CVT as an option on the A4 and A6. BMW offered a CVT manufactured by ZF (also used on the Rover 200/25, 400/45, the MGF and the early versions of the MINI) and from 2004 Mercedes-Benz offered entry-level A Class saloon equipped with its Autotronic CVT. One of the big differences between the earlier Variomatic-type transmissions used by DAF is that these later systems now used steel belts and are generally electronically controlled with the option to provide a ‘stepped’ drive with a number of pre-set ratios rather than a constantly variable gearing as in the traditional DAF system.

Technically sophisticated CVTs are becoming more popular and the system claims several advantages that make this form of drive appealing both to car owners as well as environmentalists. One of the main benefits is how CVT works to keep the car at an optimum power range regardless of speed. This helps to save fuel and eliminates ‘gear hunting’. The principle in many systems is still very similar to the one developed by Van Doorn. Sixty years is a long time in automotive engineering and CVT is definitely the ‘come back kid’ so it will be interesting to see how this innovative technology continues to be developed until electric power eventually takes over from the internal combustion engine.