The MGA has always had the looks to compare to the Italian exotics, but how does it compare to the Alfa Romeo Giulietta over 60 years on?

Words: Paul Wager Images: Matt Woods

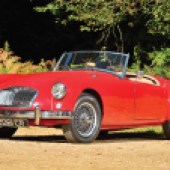

Looking at these two stylish 1950s roadsters sitting in the early spring sun, a non-car person would be hard pressed to identify which one was penned in Oxfordshire and which was sketched out in Turin, the elegant curves of the MGA more than a match for Pininfarina’s design for Alfa Romeo.

Under their shapely skin, the two cars are vastly different in their technical make-up but one thing they do share is a demonstration of just how important the US market was for European car makers back in the 1950s: some 80 per cent of MGA production was exported across the Atlantic, while the Giulietta Spider owes its very existence to the demands of American enthusiasts.

Both cars are also a reminder of happier times for their respective makers, before the compromises forced on them as part of a much bigger group in the shape of Fiat and British Leyland. Back when they were launched, Alfa Romeo was a low-volume brand famed for the quality and engineering of its cars, while MG was probably the dominant marque in traditional sports cars thanks to its popularity in the US.

The Alfa was always the pricier of the pair, the Giulietta selling at just over the £1000 mark in the early 1960s getting on for double the list price of the MGA. Today as classics there’s still a price gap with the Giulietta Spider now around the £40,000 mark, while the MGA remains a pricy proposition, albeit a more affordable one with an entry price of around £25,000. Away from the money though, how did the best of the MGs stack up to the exotic Italian?

Styled by Bertone designer Franco Scaglione and featuring a 1290cc version of the Alfa Romeo twin-cam engine which had debuted in the Alfa 1900 four years earlier, the 750-Series Giulietta range was launched at the 1954 Turin show. Initially the car was offered as a coupe only, with the saloon – marketed as Berlina – joining the range at the following year’s Turin show.

The convertible two-seater Spider is something of an aberration in the 101-Series Alfa range, since it was styled by Pininfarina and assembled not at Alfa’s own Milano facility but at Pininfarina’s Grugliasco facility, established especially for the purpose.

There’s no better illustration of the value of the US market to the European exporters than the story behind the Spider. At the time, imports to the USA were handled by legendary New York-based European car distributor Max Hoffman, who among other things was responsible for introducing the Volkswagen and Jaguar brands successfully to the USA.

He may have been only an importer but when the Austrian entrepreneur and former racing driver picked up the phone to Stuttgart or Milan, even iron-willed auto executives took notice. The Mercedes 300SL Gullwing and Porsche 356 Speedster were both developed as road cars following Hoffman’s insistence that there was a ready market in the USA for the cars, while he was also instrumental in the development of the BMW 507 and imported BMWs to the Eastern USA until selling out to BMW in 1975.

Clearly, Hoffman knew his stuff – although he admitted that giving up on the VW brand in 1953 was a mistake – and when he suggested that a convertible version of the Giulietta would be attractive to US buyers, Alfa was prepared to create it. The design of the car was put out to tender back in Italy and it was Pininfarina’s work which was selected for production. At the time the firm was on the cusp of taking the leap from small-scale coachbuilder to volume manufacturer and a contract with Alfa Romeo to assemble the car was the push it needed to develop a new factory outside the city.

Hoffman had insisted that the car would need to be a step up from the Triumphs and MGs of the time, with a proper convertible top and wind-up glass windows. For buyers used to cruise control and air conditioning in their full-size Chevys, slot-in side screens and no door locks simply wouldn’t do. Hoffman assured Alfa Romeo that he could sell all the cars they could produce, backing this up with a firm order for 600 cars. With this in mind the Pininfarina works were geared up to produce the Spider at the rate of 20 per day, with the first cars all heading to America to fulfil Hoffman’s order.

The Giulietta Spider was introduced to European buyers at the 1955 Salon de l’Automobile in Paris and was an immediate hit, combining the well regarded drivetrain of the Giulietta saloon with the elegant convertible style.

It drove as well as it looked, too. With a kerb weight of just 820kg, the 79bhp produced by the free-revving twin-cam 1300 motor went a long way and testing the Giulietta saloon in 1964, Autocar was moved to admit “British manufacturers do not produce a model comparable with the Giulietta.”

Approaching the Giulietta Spider today, you need to set aside all the modern-day clichés about the Alfa Romeos of the ’70s and ’80s: the dodgy electrics, shoddy trim, failing plastic and wonky panel gaps were all still in the future for the proud Alfa Romeo of the mid ’50s, a firm which was confident enough to price its saloon cars up against Mercedes.

The Spider feels very much a product of the 1950s, with its delicate detailing and intricate decoration but all the same it’s a world away from the British competitors of the day. The door is opened with a neat pushbutton external handle rather than requiring you to reach inside, while the door itself is fully trimmed. Once inside, the seating position is similar to the MG with a low-set seat, high scuttle and a big slender-spoked steering wheel.

Twist the key and the Alfa engine may not sound any more exotic at idle than the MGA’s B-Series, but give it some revs and the difference is immediately obvious. Not only is the Alfa motor an overhead cam design but boasts two of them, which is how it manages to produce 11bhp more than the MG from a 200cc smaller capacity.

The plain figures don’t tell the full story though; it’s in the driving experience that the more expensive engineering of the Alfa shines through. Drive it hard and it doesn’t feel like you’re abusing a 60-year old car, with the engine happy to rev and the rest of the car designed to keep up. The car still only has four gears on offer but the ratios are better spaced to avoid the often awkward second-third gap on British products of the day, while there’s synchro on all forward gears to make life easy.

On the move, the Alfa feels more modern thanks in large part to its unitary construction against the MGA’s separate chassis but aside from the lever arm dampers of the MG, the two are similarly specified in the suspension department: both employ front wishbones and coil springs with a live rear axle, although the Alfa uses coils while the MGA is of course leaf-sprung.

The coil-sprung monocoque Alfa offers more wheel travel than the MGA and as a consequence a softer ride. Both will cling on when asked, but the Alfa will exhibit more body roll than the MG, feeling more like the saloon-based design it is. On a longer trip, it’s the more comfortable companion and nobody is going to drive either of these cars on the ragged edge today, meaning that the joy is to be had from setting the car up for faster, sweeping curves than opposite-locking round hairpins.

In short, it’s easy to forget the age of the Alfa from behind the wheel and it’s nice to be reminded that once upon a time – even if that time was increasingly far away – there was some substance to the hype behind Alfa’s modern marketing.

The genesis of the MGA is rather better known than the Giulietta and a great deal more straightforward. Much like the Alfa though, it owes its very existence to the demands of the American market, since BMC chairman in the early 1950s, Leonard Lord, was only persuaded to allow its development when sales of the prewar T-Series models started to collapse rapidly as the car’s age became increasingly obvious.

MG had been desperate to develop a replacement for some time and had even worked up a prototype on the quiet, using a sleek new body penned by MG’s Syd Enever for an MG TD Le Mans racer the previous year.

At the time the ink was barely dry on the contract between Lord and Donald Healey which had created the Austin-Healey brand and understandably he was reluctant to create an in-house challenger. A year later though, the sales of the MG had slumped so catastrophically that the green light was given to the project which was intended to be the first in a new generation of MG products – hence the ‘A’ in the name.

Taking the Le Mans-derived car as a basis, development work was swift and in 1955 the car was ready for the show stand at Frankfurt. Enever’s bodywork largely remained, but the chassis’s frame rails had been spaced out, allowing the seats to drop down inside them for a lower-slung stance.

Underneath, the suspension was largely lifted from the MG TF, but when it came to the engine, the delay proved to be a blessing in disguise, since the old XPAG motor could be replaced by the newly-developed B-Series engine as found in the BMC saloons. In 1489cc form it produced 68bhp and as a bonus meant the production car wasn’t saddled with the huge bonnet bulge the prototype had needed to clear the older engine.

The B-Series lacked the exotic specs of the Alfa motor but it was a far more modern design than the old XPAG engine and gave the new MG a crucial showroom appeal. In later incarnations, it would jump to 72bhp, then 80bhp thanks to a stretch to 1588cc and then 1622cc which provided the MGA with 102mph pace.

The 1956 car you see here though is the MGA in its original 1500 form boasting 72bhp. although a more direct competitor to the 1961 Giulietta would have packed the 80bhp of the 1600. Despite the low-tech pushrod approach, it acquits itself well on paper, matching the Alfa’s 101mph top speed and being only a second slower to 60mph.

The MG is decidedly more traditional than the lavishly trimmed Alfa, as evidenced by the rope-pull door release, the cutaway doors and slot-in side screens but on a sunny day little of that is obvious and the emphasis is on the driving appeal. And it’s here that the MGA, despite its less exotic make-up is a worthy opponent to the Italian. There’s a delicacy to the way a nicely prepared MGA drives which makes the later MGB feel somehow stodgy and uninspiring. In 1500 form like this, the B-Series seems crisper and more eager than it does in its larger sizes and despite its age, the MGA can be driven confidently in modern traffic.

Like the Alfa, the MGA’s capabilities are ultimately higher than the average driver would wish to explore in a cherished car of this age today and there’s a pleasure to be had from mastering the mechanics of driving smoothly. The rack and pion steering set-up makes it easier to place an MGA than many a 1950s car, A-road progress being accomplished without a constant sawing at the wheel, especially on modern radial tyres. Yes, the ride is more bouncy than the Alfa but notably less jolty than the Triumph TRs of the period with their short wheel travel.

In fact, if you’d never lifted the bonnet you wouldn’t have let talk of twin camshafts cloud your mind and the two cars – at the same time so very different yet so very similar – would feel like worthy rivals.

MGA vs Alfa Romeo Giulietta Spider: our verdict

Concentrate on value and it’s easy to choose a winner here: the Alfa in our photos is currently advertised at £55,000 and the MGA recently sold for just £35,000. As a confirmed Alfa fan, the Giulietta was my choice even before I typed the first sentence, but it’s hard to overlook the cold logic which makes the MGA the more practical car to own and the ultimate winner. Parts supply for the MGA is superb and you won’t live in fear of an irreplaceable trim detail or body panel being damaged… which ultimately means you’ll most likely get more use and more enjoyment out of it.

Of course it’s not every time that we let logic prevail though and there’s no denying the appeal of the Alfa which brought a touch of the exotic to the 1950s mass market. If the budget doesn’t stretch to a 1950s Ferrari then today, as it was back then, the Alfa is a worthy alternative.