We discover that less really can be more when it comes to the diminutive, desirable and affordable Austin A35

After messing about with and writing about old cars for more years than I care to remember, I’ve sampled everything from Alfa to Zastava but there are a few which will always stand out. Naturally, some are exotics like the Jaguar C-type and ’50s Bentley Continental, but perhaps surprisingly it’s the more humble machinery which leaves more of an impression. Two which immediately spring to mind are the Frogeye Sprite and the Austin A30/A35, both of which provide grins per mile far in excess of what you’d expect from the modest power outputs of their A-Series engines.

Launched as the A30 in 1951, the baby Austin was born from the failure of a proposed Austin/Morris collaboration in 1949 which meant that Austin needed to create a competitor to Morris’s strong-selling Minor. This would effectively be a replacement for the old Austin Seven and indeed early publicity marketed the A30 as the ‘New Seven’.

Austin recognised that the Morris Minor offered the road manners of a larger, more costly car and was aware that its own entry-level offering would need to be similar. Much like the original Seven, the new car was designed as ‘a small car in miniature’ and some advanced engineering was employed to create it.

Perhaps the most notable feature was the bodyshell construction, a monocoque which made it the first truly ‘chassis-less’ car produced in Britain. Some European competitors could claim to have beaten Austin to the prize but back at home many cars claiming to feature unitary construction still featured elements of a chassis, usually welded to the underside of the bodyshell. Not so the Austin, which featured no trace of a chassis thanks largely to the advances in stress analysis and construction techniques gained from the aerospace industry during the wartime period.

It was an innovative move by the normally conservative Austin and when engineers at rival Morris tested the torsional rigidity of the finished shell they were surprised to discover that it was twice as stiff as the Minor.

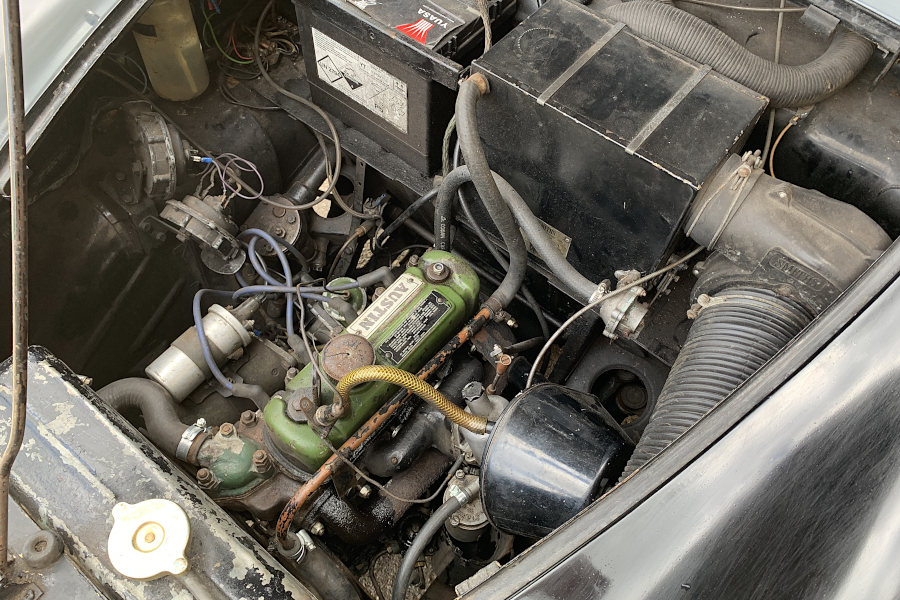

The new car also debuted the A-Series engine which would live on into the 21st century and would also be installed in the Minor after Austin and Morris finally merged in 1952. Ironically, the A-Series would be offered for longer in the Morris than it was in the Austin for which it was designed, with over 14 million engines being produced in total and the unit found in most of the Bl-era models.

Effectively a scaled-down version of the powerplant found in Austin’s larger models, the overhead valve A-Series was sophisticated in an era when most small cars still used a sidevalve layout.

Thanks to the involvement of noted cylinder head designer Harry Weslake, the unit also featured an impressively efficient combustion chamber design and its combination of torque and economy were chief among the reasons Rover found it so tricky to develop a cost-effective replacement even in the ’90s.

The idea of a large car in miniature is particularly evident in the Austin’s ‘Honey, I shrunk the Packard’ styling, clearly influenced by American trends of the era. The first models were created with input from the Raymond Loewy studio, but the design would later be modified by in-house Longbridge stylist Dick Burzi after management requested a raft of cost-cutting measures including lopping 4.5 inches from the car’s length.

Despite this, the result is pleasingly well-proportioned and certainly distinctive, that reduction in length actually helping to preserve the proportions since the finished car was just 1.4m wide – or 150cm narrower than the Moggy.

As launched in A30 form, undercutting the Minor by some £100 at £507, the car boasted just 28bhp from the 803cc version of the A-Series but by the standards of the day that was respectable enough.

In 1953, a two-door body was added to the range and in 1956 more comprehensive changes created the A35, identified by flashing indicators replacing the trafficators and the painted grille with chrome surround. Meanwhile, the most significant upgrade was a boost to 948cc and 34bhp, which when paired with revised gearing made a big difference to the car’s real-world performance.

The A30/A35 was a big seller for Austin, but the launch of the Mini in 1959 rendered it obsolete, with the car effectively replaced by the larger A40 Farina. By then, over 223,000 A30s and nearly 130,000 A35s had been produced, plus the van and estate derivatives taking the total to over 350,000 which isn’t a bad result for an eight-year production life.

Despite this, it’s dwarfed by the 1.6 million Minors which left Cowley, but today this makes the A35 the lesser spotted of the duo and a neat opportunity to be slightly left-field with your classic choice.

Which is why we jumped at the chance to revisit the A35 courtesy of the 1958 example you see here for sale at Pioneer Automobiles near Chieveley. A typical example of the A35, it boasts a lovely patina which reflects the fact that the values of these cars don’t justify no-holds-barred restoration and as a result is a beautifully honest old car with a story to tell.

Approaching the A35, it always seems so tiny but I never fail to be surprised by the car’s Tardis-like cabin which offers proper seating for four adults, even if elbow room is a bit tight. There’s plenty of headroom and the driving position is actually remarkably comfortable with footwells usefully larger than many 1950s cars which makes it easy to operate the typically tiny pedals.

There’s a separate starter button on this ’58 car and the sound of the A-Series is reassuringly familiar, as is the clutch operation. As with so many British cars of the period, the pedal offers a long travel with all the engagement happening within only a very small part of its movement, but it only takes a few minutes to get used to.

It’s an easy car to drive, modern enough to be familiar in many respects with an easy shift action and light steering at anything above walking pace. Its modest width also makes it ideal for country lanes, able to squeeze past oncoming traffic where modern SUVs struggle and end up scraping into the hedge.

That doesn’t mean you can pilot an A35 with abandon though, since one area where its 1950s genesis shows is in the stopping power. The braking system is an unusual hybrid of hydraulic and mechanical, with the master cylinder operating the wheel cylinders in the front drums in the conventional way, while a single slave cylinder at the rear operates the rear brakes mechanically via pushrods.

Even by 1950s standards the system was only ever adequate and for someone unfamiliar with old cars the high pedal effort and lack of immediate bite takes some getting used to. In truth it’s on a par with a Minor on standard unassisted drums, and if you drive the A35 sensibly – and with due sympathy for what is a 70-year old car – it won’t be an issue.

Otherwise it’s easy to make surprisingly brisk progress in the A35, the car seldom holding up traffic and able to hold its own comfortably on A and B-roads. The steering uses a box which means it’s less precise than the Minor’s rack, but this example proved remarkably well sorted and required little of the sawing at the wheel you often find yourself doing in ’50s cars at cruising speeds.

In fact there’s a joy to be had from mastering the A35 – conserving momentum, judging stopping distances and stirring the gearlever to keep the eager A-Series on the boil – which is superbly satisfying for anyone who enjoys classic engineering. It’s also the reason why you can’t fail to step out of every trip in one of these Austins without a big grin.

Back in the day the road testers reckoned the relatively tall and narrow A35 was beaten in the handling stakes by the Minor, but in truth there’s little to choose between them given the nature in which you’re likely to drive a car of this age. Perhaps surprising though, I reckon the Austin has a slight edge when it comes to ride quality, lacking the bottoming-out the Minor’s rear end often displays on undulating or rough roads. The seats also feel more supportive than the Minor’s pews, which tend to swallow you up on longer journeys to create what one notable Minor specialist refers to as ‘Morris arse’.

It all adds up to a package which is surprisingly usable in modern life and a car which makes for an unexpectedly practical choice. Certainly, its slender width and great fuel economy make it a great city car, while the satisfaction of driving it smoothly means it’s as much fun as any traditional classic sports car. Oh and there’s plenty of room for anyone wanting a lift home too.

Thanks to Pioneer Automobiles where you’ll find this 1958 Austin A35 in stock at £4950. A very honest and solid example with nice chrome, it comes with a great history including two old-style buff logbooks plus new front brakes. As we discovered, it’s very much on the button and drives nicely. You’ll find full details here.