Just over three decades have passed since BMW acquired Rover from British Aerospace in 1994. Here’s the full story

Words: Paul Wager

Just over 30 years ago, Tim Sainsbury as Minister for Industry made an announcement at 3.30pm in the House of Commons: “With permission, Madam Speaker, I should like to make a Statement about BMW’s acquisition of Rover.

“This morning, British Aerospace announced its decision to accept an offer from BMW to acquire its wholly-owned subsidiary Rover Group Holdings Ltd.”

British Aerospace had owned 80% of Rover Group since July 1988, having bought it from the government in a controversial £150m deal and its intention to offload the car-making business had been public knowledge for some time, since the original agreement required it to retain ownership for just five years. BAe needed to free up cash to invest in its turboprop and regional jet business and a cash-hungry car maker was denting its competitiveness on the world defence stage.

For BMW, it represented an opportunity to move into volume car making where industry pundits were all agreed at the time that the big money was to be made; the accepted wisdom was that small niche players like BMW operating only in the upper end of the market were vulnerable in the long term.

Rover, the pawn in the middle, had little say in the matter although the deal was naturally presented as an opportunity. Acquiring a new brand would avoid the problems with diluting the BMW brand by producing smaller, cheaper cars.

Various other reports, both academic and otherwise have since suggested that BMW may have had other less obvious reasons for eyeing up a British maker: at the time Sterling was relatively weak, which together with the UK’s by then less aggressive labour relations made it a cheaper place to produce cars than BMW’s German plants. It’s also been suggested that the Germans were keen to compete with Mercedes and other premium brands in the SUV market but lacked the resources to develop its own models from scratch – and Rover Group came with the prize of the Land Rover brand.

BAE chairman Dick Evans (left) and BMW’s Bernd Pischetsrieder

Behind the scenes though, Rover Group management had been scrabbling frantically to avoid being swallowed up by the Germans. Since 1989, Honda had owned 20% of Rover but maintained a belief that Rover was capable of surviving independently and was unwilling to take full ownership. Instead, it offered to increase its holding to 47.5 per cent, an offer which valued the company at £600m.

BMW’s offer came in at £800m – far in excess of Honda’s valuation – but Rover management was by all accounts keen to continue the Honda collaboration, keen enough for boss George Simpson to book himself on the first flight to Tokyo in the hope of persuading Honda to up its offer. He was told that Honda had no interest in a majority holding and within days BMW’s chairman Bernd Pischetsrieder was in London to sign the deal, posing for that famous photo of him between BMW 7-Series and Rover 600.

Honda was apparently surprised by the move, its spokesman portraying the firm as betrayed and disappointed but as pointed out by David Bowen in The Independent, this could simply have been wounded pride from a firm which realised it had been out-manoeuvred by the Bavarians.

So why the Honda reluctance to acquire Rover? It’s been attributed partly to Japanese sensitivities over the question of foreign ownership and no doubt there’s some substance in that: Honda would have been fearful of the public opinion if it was seen to take over the last British car maker. The firm also valued Rover for its very British identity and to lose that would lose much of its value to Honda, while the third reason is simply that BMW at the time had huge cash reserves and could easily afford to buy Rover.

The two firms were deeply entwined, too: Honda provided engines for Rover models, while Rover’s Swindon pressings plant supplied panels for Honda. Lord Strathclyde’s statement to the House of Commons suggested “BMW have also stated that they hope that Rover will be able to maintain and to build on the existing links with Honda.”

The reality of course was very different. Almost the entire Rover range at the time depended on either Honda engineering or design to some degree and just a month after the announcement, Honda divested its shareholding and built a new press shop at its Swindon plant.

It might be reasonable to expect that this would be the cue to some frantic new model development funded by the new owners but the reality was rather different. The Honda-based 200/400 was already well into development and so went ahead as planned, accompanied by the smaller 200 which was developed as a Metro replacement, while the 600 was already in production but was essentially a rebadged Honda Accord.

Rover 600’s Honda technology made it costly to produce

The original licence agreement with Honda was conditional on the firm remaining in British ownership, which meant the firm was immediately in an awkward position.

BMW boss Bernd Pischetsrieder even flew to Tokyo to discuss the matter with Honda president Nobuhiko Kawamoto but Honda was having none of it. Shortly afterwards it renegotiated the licence deals and of course the cost went up, the Honda-based cars now costing significantly more to produce.

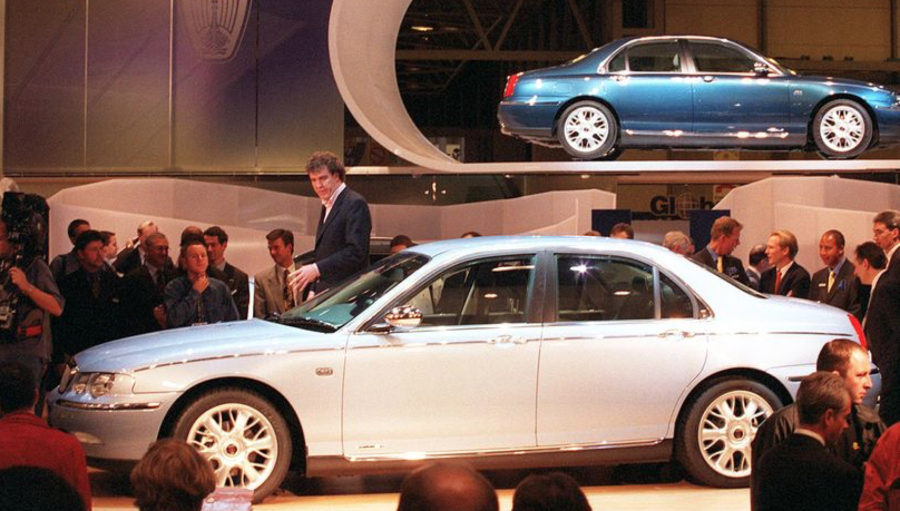

The 600 was hit particularly hard by this, so BMW’s initial efforts concentrated on developing a new model which could replace both the 600 and the ageing 800. This car would be the Rover 75 – and with BMW’s expertise and financial resources, it was a genuinely world class contender.

It was a shame then that Pischetsrieder famously chose the occasion of the car’s launch at the 1998 NEC motor show to torpedo both the new car and the entire company with what now seems like an amazingly ill-judged speech.

BMW had based its turnaround plan for Rover with Sterling Dm2.90, but by 1998 it had risen to Dm3.20, which had increased costs significantly and Pischetsrieder announced that the future of Rover was in doubt unless the UK government stepped up with the requested subsidy.

Sadly, his timing may have been terrible but he had his figures right: the following year Rover’s market share collapsed to 6.5% and with the mounting losses – £570m in 1998 – threatening to drag down the BMW group, Pischetsrieder was made the scapegoat and left the company.

The Rover 75 was well received at launch despite Pischetsrieder’s poorly timed speech

His successor was Joachim Milberg, who demanded Rover enter profitability by 2002, but with BMW’s controlling Quandt family getting anxious, time had run out and by March 2000 the board publicly announced that Rover was once more for sale.

Negotiations were swift: on May 10, the Phoenix Consortium acquired the MG brand and the Longbridge site for a symbolic £10, while at the same time Land Rover was sold to Ford for £1.8bn and BMW retained the Mini brand and the Cowley facility.

Turbulent times would follow for all of the brands tangled up in that hastily arranged press call in a windswept Cofton Park 30 years ago, but each one deserves a feature in its own right.