Is it a bad idea to buy and live with a cheap Bentley Continental Flying Spur? We’re on a mission to find out

Words and images: Paul Wager Sponsored editorial in association with IntroCar

Buy cheap, buy twice goes the saying and nowhere is it more appropriate than our experience acquiring a Bentley Continental GT. Backed with a confidence which comes from gambling company money rather than personal cash, we set out on a mission to discover whether a Continental from the bottom of the market can be a worthwhile project – or an expensive disaster. And it’s fair to say we’ve learned a lot on the way.

After trawling the bargain end of the Continental market, you’ll find there’s always someone who brightly offers a comment along the lines of “You paid how much?” before commenting how they could have found you one so much cheaper than that. But, in reality, it’s not that straightforward.

At the sub-£20k mark, there’s actually not a lot of choice once you’ve weeded out the Category N cars and the badly modified examples with aftermarket go-faster bits glued to the bodywork, black-painted wheels and dubious vinyl wraps hiding who knows what.

Yes, you can find a Continental GT in an auction for as little as £8000 but unless you have a lot of spare time on your hands and your own workshop facilities – crucially, with a two-post lift – then you’re wise to avoid them. These cars can be hiding some horrifically expensive problems and they’re usually the reason why they’ve been entered into a trade sale.

Our first foray into Continental ownership took the form of this outwardly respectable GT. However, diagnostics revealed a staggering 110 fault codes. Sadly, it was sidelined by overheating problems among other issues

Similarly, private buyers can also be concealing potentially costly problems, although clearly there will also be many well-loved examples out there being moved on for genuine reasons. In fact, one of the biggest bugbears with these cars is lack of use, which can cause far more issues than high mileages and so many cars offered privately will boast of their low mileage – which isn’t always the selling point it might seem.

It was for those reasons that we decided to break with tradition and acquire a car from a retail trader, both for the benefits of the consumer protection it offers and also for the very simple reason that most traders don’t want to see their cars coming back and so will have prepared them to at least a basic standard.

And so it was that after sifting out those write-offs and modified cars, we narrowed it down to just two candidates, one of which was a promising-looking GT at a trader in the South West. Showing just over 120,000 miles it was a 2005 car and came with the benefit of the Mulliner Driving Specification which adds the more modern-looking diamond quilted leather and aluminium trim.

After test driving the car, it seemed ideal for our purposes with the bonus of a few jobs which would make great DIY how-to features: removing the bumper to properly flat and polish the faded headlamps, fixing the inoperative rear spoiler and sorting the droopy headliner. The mileage wasn’t a great concern since it translates to a respectable 6600-per-year average over the car’s lifetime and it came with a bulging folder of history, including some recent invoices from Bentley main dealers covering a couple of the more expensive issues you get with these cars.

Accordingly a deposit was put down and arrangements were made for our finance people to transfer the balance. For various reasons we then weren’t able to take delivery for some time but eventually the GT arrived on the back of a trailer and off we went.

All was well for about two miles until, stuck in traffic, I noticed the temperature gauge running higher than usual. It’s the same gauge arrangement you’ll find in a contemporary Mk5 Golf, but whereas the Golf’s needle points straight upwards to 60°C in normal use, the W12 engine runs at a hotter 90°C, so the needle sits at about two o’clock.

Assuming nothing much was therefore wrong, I thought nothing of it until I took the car out again and half-way up a steep hill the water needle soared into the red zone. Knowing the cost of replacing the head gaskets on the W12 effectively writes a Continental off financially, I pulled over immediately and, having let it cool, checked the water level.

Allowing for the amount which had spat out angrily on removing the pressure cap, it did at least seem to be full of water so I nursed it home, discovering by accident that slipping it into neutral and revving it hard did seem to bring the temperature down.

At this point I enlisted my local garage for a diagnosis, since they already have a few Continental-owning customers. After pressure-testing the cooling system overnight, the good news was that the head gaskets appeared to be fine, their diagnosis being a thermostat, water pump – or both.

Those split rim alloys might need refurbishing but the rest of the car looks tidy enough

At this point, I honestly began to question the wisdom of buying an early GT: on pre-2007 cars the thermostat is an electronically-controlled unit and retails for over £720 exchange, while an aftermarket water pump is a more affordable £130 but needs the entire front end of the vehicle removing in order to access it. The workshop manual instructs you to simply pop off the bumper skin and then ‘swing out’ the water and air conditioning radiators but after 20 years it’s a fair bet that ‘swing out’ translates to ‘sweep up all the rusty pipes and broken clips’ so it’s potentially a big labour bill.

Throw into the mix the gloopy gearbox oil stain the car left on my otherwise spotless driveway thanks to cooler pipes which looked as if they’d been damaged on the slightly-too-small delivery trailer and I was already regretting our brief adventure into Continental GT ownership. Especially once I’d hooked up the VW Group diagnostic software on my laptop and discovered that our new acquisition was displaying a colossal 110 fault codes from its various electronic control modules.

One of these was particularly alarming since it related to an intermittent boost control problem on cylinder bank two. On pre-2006 cars, the boost control modules sit above the gearbox, meaning that replacement involves the mammoth job of dropping the engine and gearbox, whereas later cars moved them to the front of the engine.

Needless to say, much head-scratching followed and, to cut a long story short, the extra cost of buying from a trader proved justified when the vendor offered to have the car back and fix it. Fair enough, we thought, and it was duly collected. At which point we waited… and waited… and waited. Two months later, our friendly vendor threw in the towel, admitting defeat after having replaced the thermostat and water pump but still not having sorted it.

Bare screws on the number plates are a pet hate, especially on a car like this. Luckily I had a bag of screw caps in the garage

At this point we were back at square one, still needing to source a Continental but at least now rather better informed on these complex cars. It tells you a lot that many of the examples I’d originally considered were still for sale, but when several specialists suggested widening the search to include the GT’s four-door brother, the Continental Flying Spur, things looked up.

The four-door cars attracted a different kind of buyer it seems, especially as they aged and have generally lived a much more gentle life, making them an ideal first dip into the waters of Continental ownership.

One in particular caught my eye, which was the 2008 car you see here. It’s covered a chunky 143,000 miles but is in simply lovely condition having spent a large part of its life in service as a VIP chauffeur car. The service book is fully stamped up, the Mulliner interior is pristine and it comes with the glorious feature of massage seats… front and rear.

It’s not perfect, of course – few of these cars don’t have at least one minor issue and in fact even the 2004 car in Bentley’s own heritage collection had a warning light glowing when I tried it recently. The electric bootlid isn’t working properly, which means a careful manual assist is needed to get it to close and latch, while the EML light comes on after a hot start owing to the common – but generally easily fixed – problem of a leak in the secondary air injection system, usually caused by a split connecting pipe.

On the other hand, compared to the 110 faults logged on the GT, the laptop threw up just three on the Spur and it drives superbly. The combination of wafting luxury and relentless shove when required is very much a USP of these cars, and even the 5m long Flying Spur is seriously fast.

Chipped legend on the ‘Engine start’ button is common. This £2 sticker supplied by www.isaydingdong.co.uk is a neat way to tidy it up without dismantling the console

As I write this we’ve not had the car more than a few weeks, so work has been limited to idle tinkering: I’ve covered up the ugly bare screw heads in the number plates with plastic caps and used a neat sticker to conceal the chipped legend on the engine start button. A replacement case is on order for the dog-eared spare key fob and hopefully a temporary (for which, read gaffer tape) fix can be performed to sort that air injection error.

Hopefully this won’t be a case of fiddling around the edges though, since the car is currently booked in for an assessment with a respected Bentley specialist who can give it a good going-over and with the benefit of their professional experience tell us whether it really is a case of second time lucky.

Bentley Continental GT expert inspection

The car was booked in for an assessment with Nigel Sandell, the independent Rolls/Bentley specialist in Isleworth. What Nigel and the team don’t know about Rolls-Royces and Bentleys of all ages is frankly not worth knowing, so it was with some trepidation that we pointed the Flying Spur East down the M4.

Since acquiring the car, we’ve covered nearly 1000 miles which has given me time to discover any other faults which may have been lurking behind the scenes but so far nothing alarming has been thrown up.

The engine management light has been glowing from day one which seems to be pretty much standard with the Continental, while we were already aware of the failed electric bootlid and the inoperative offside rear headrest which shorter passengers find uncomfortable.

One thing I had been keeping an eye on was the slightly sketchy nearside rear tyre which a MoT tester friend pronounced legal but which I wouldn’t have fancied being questioned about at the roadside.

If there was anything (apart from the obvious) wrong with our Flying Spur, these guys would quickly find it

Accordingly, the Spur was booked in for a new Pirelli P Zero to be fitted, matching the newish-looking tyre on the other side. No sooner had I wandered off to buy some lunch though than the fitters were on the phone asking where the locking wheel bolt key was.

You know the rest of the story… the car was turned inside out looking for it to no avail and liability concerns meant the tyre depot was reluctant to remove it using brute force.

Off I went with the tyre in the boot, but on a whim called in at my local garage where they laughed at the challenge and within minutes had extracted the locking bolt using a 19mm spline bit and a big hammer.

New tyre fitted and a set of used bolts ordered, I was rather happier to drive the car on the motorway and off we went to Isleworth where Sandell’s resident Continental specialist Jonny O’Neill was ready for us with a laptop and a lift.

A full appraisal of this kind is very similar to an MoT test and covers many of the items which would generate a fail, but goes beyond that in many ways with general advice on potential future issues and the general health of the car.

The assessment itself takes three different stages: a general appraisal with the car on the ground, followed by a session with the diagnostic kit and then an examination of the underside with the car on a lift.

Using a tablet computer, issues are split into green, amber and red, with the red naturally being the items which need immediate attention, and a useful report is generated at the end. So how much ‘red’ did our 144,000-mile Spur generate?

Continentals tend to eat batteries so a proper health check is useful

With the car on the ground, Jonny’s initial walk-around immediately revealed a couple of minor issues: the outer lens is missing from the driver’s side door mirror, while the wiper blades are incorrect, with the tip of the passenger one touching the bodywork at rest. The mirror has clearly taken a knock at some point, since the electric fold action doesn’t stop until it physically hits the door glass which suggest the internal stop is damaged.

The inoperative electric bootlid is something of a mystery. Pressing the release switch makes the motor hum but there’s no movement in the lid itself, suggesting the drive has either failed or somehow been disconnected.

Further examination showed that the offside hinge has been welded at one point, while various scrape marks around the latch suggest the system has failed closed in the past and been disabled. The emergency cable release – normally routed neatly out of sight and accessed by removing a rear seat cushion – has also been rerouted for easy access through the armrest hatch.

Apart from the panel not sitting quite flush on one side, it’s not the end of the world and since it can be closed manually, we’ll leave it for now. It’s also a common issue on Continentals, both the GT and Flying Spur.

Elsewhere, all the electrics work properly and the bodywork is really pretty tidy. Even the soft-close door latches and the keyless entry work properly, while Jonny was happy with the car’s level stance which suggests the air suspension is in good health, even if it is possibly a touch nose-down.

Under the bonnet we discovered that the air filters are clean enough to pass inspection and everything else seems up to scratch, although we did spot a cable tie holding the wiring plug to a sensor under the slam panel and the brake fluid looks as if it’s due for replacement.

Locking tab for the connector to this air injection sensor has obviously broken in the past, with the plug now held by a cable tie

With the initial walk-around done, it was time to get serious with the computer diagnostics, but before doing this Jonny wheeled out the battery charger to ensure that a voltage drop didn’t cause issues during what can be a lengthy process with the ignition on.

As part of the appraisal, before connecting the charger he conducted a proper battery health check – something which is more important than you might think on the Continental. These cars use two batteries, with a hefty 85Ah one on the left used as the main battery and the 61Ah on the right used only for starting.

There’s a neat trick built into the system which allows you to start the car even if one battery is low: twist the ignition key the other way and it will use the other battery to start. Given the Continental’s habit of flattening the battery when left parked for more than a few days, this naturally means that many owners constantly use the feature and consequently one or more of the batteries is generally below par.

In our case, things weren’t too bad. The main battery isn’t a genuine Bentley one but it is the correct AGM specification and the electronic tester pronounced it in acceptable health. An old-school resistance ‘drop tester’ tool has to be used on the other battery but that checked out fine too, so with the charger connected we could get on with the rest of the diagnostics.

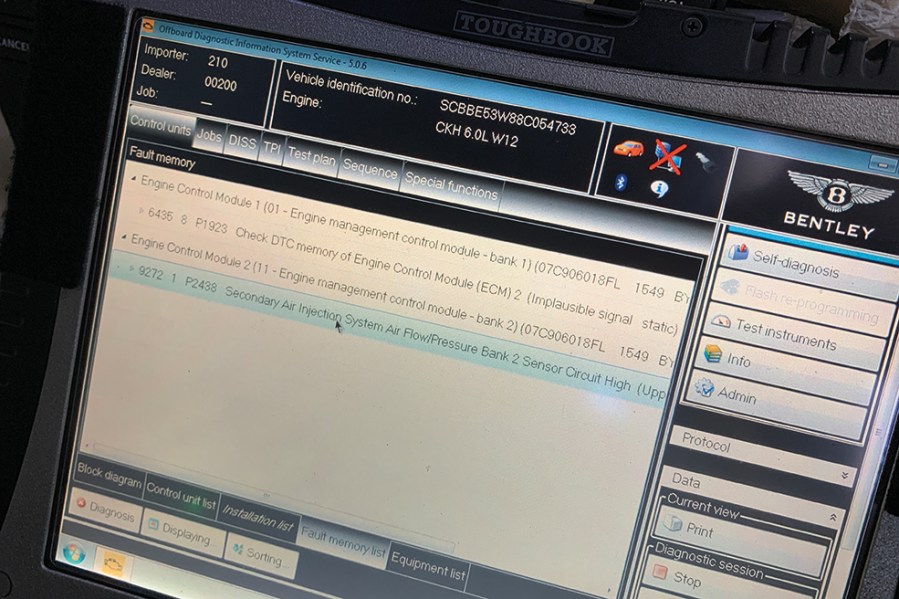

For this, Nigel Sandell uses the dealer-level ‘VAS’ system licensed from Volkswagen Group which, as you might expect, does a rather more comprehensive job than a basic OBD scanner and even some of the aftermarket VAG-specific software.

The Volkswagen Group software used by Nigel Sandell is the same as you’ll find at the main dealer

When it comes to the Continental, the codes thrown up during this part of the process can be the big-ticket items and we weren’t surprised to find a screen full of fault codes.

Many of them are intermittent, or historical faults thrown up long ago and often relating to issues like flat batteries. However, two needed more attention. The first was an exhaust gas oxygen sensor code which was present for both banks of the W12 engine and which can be tricky to fix owing to the limited access around the massive engine. Worst case scenario is an engine-out job, although Jonny reports having changed a couple by loosening the engine mounts and lowering the rear of the engine just enough to gain access.

The second was an ‘insufficient flow’ fault in the secondary air injection system for bank one which indicates that a replacement pump may be needed. A fault code for a faulty sensor on the same system for bank two was also listed, quite possibly explained by the cable tie holding the broken plug to the sensor which we’d noticed earlier.

Annoyingly, the air pump replacement is a much harder job on bank one than it would be on bank two which probably explains why it’s not been fixed: the front wing and the arch liner both need to come off to access the pump.

Not the best news then but at least we were already prepared for the air pump issue. What would we find with the car up on the lift?

Two of the three strut top bolts were either never tightened or have worked loose

A huge amount of play in the offside front wheel was the immediate answer. As Jonny grabbed the wheel to check the condition of the wheel bearings, it was obvious from the massive movement that something wasn’t right.

As we peered into the arch, he spotted the likely cause: the alloy top plate for the air strut should be bolted into the bodyshell in three places, yet we couldn’t even see a bolt in one of the holes and the entire assembly could be moved noticeably by hand.

Lowering the car, we took a look from above and discovered that of the three strut mounting bolts one was visibly loose, one was merely finger tight and only one was secure.

As Jonny pointed out, these are stretch bolts which shouldn’t be reused but we’re guessing that’s what was done, since the strut itself looks as if it’s been replaced recently.

Luckily, the workshop had the correct parts in stock and three brand new bolts were duly fitted and torqued up to the required 50Nm pus 45 degrees, that final twist being the stretch which locks them in place.

These stretch bolts shouldn’t be re-used which may well explain why they were loose. Needless to say, new ones were fitted on the spot

With that done, we were looking for more corner cutting around the front right wheel but to be fair everything else did at least seem to be tight and safe. The bushes in the top arm are well past their best, but the bushes elsewhere have been replaced by purple polyurethane items, including those on the anti-roll bar drop links. It’s a curious modification on a car like this, since these harder poly bushes are usually used on performance hatches or track day cars, but it’s perhaps explained by the split design which makes for an easier fitment – the originals can be cut off and the poly bushes fitted without needing to take parts off the car and press them into place.

More alarming was the state of the outer CV boot on this corner, which is clearly leaking grease, although we couldn’t easily see an obvious split in the rubber.

With the wheel off, we could also check the brakes and although they’re fine for now, the pads aren’t far off needing to be replaced, while the slight lip on the discs suggests they may also need replacing at the same time, since Bentley doesn’t allow a huge wear tolerance for front disc thickness: new parts are nominally 36mm and the minimum is 34mm.

Elsewhere, the power steering pipes which are often corroded look to be in good condition, but the radiator is starting to look tired at the bottom. Since replacement involves removal of the front bodywork, it’s a big job so one which will be left until it’s absolutely necessary but we’ll be keeping an eye on the temperature gauge and the water level.

Perhaps more concerning was the state of the front bumper, which looks fine from standing height but from underneath has obviously hit a speed bump or similar. Indeed, this might well explain the replacement air strut, since the incident has obviously torn off the front undertray and scrape marks are visible on the exhaust further back.

Impact damage to the underside of the bumper has been fixed with this ugly and frankly unbelievably bad wood bodge

To add insult to injury, a truly horrible repair has been performed on the underside of the bumper where a crack in the plastic has been fixed with a block of plywood and two countersunk wood screws.

It’s nothing which can’t be tidied up though and Jonny reckoned our Spur was refreshingly rot-free underneath for a Continental of this age.

Moving backwards, we discovered a likely cause of the tinny clang heard when slamming a rear door, which is down to the loose heat shield around the compressor for the air suspension. The bad news is that the fragile securing studs have obviously sheared off, but the good news is that the holes they leave behind can be used to pass bolts through from inside to secure it properly… and it also suggests the compressor has probably been replaced.

As we moved further backwards, the final item we discovered was a cracked clamp on the nearside rear exhaust section. As Jonny points out, if this fails then the rear silencer can drop to the ground, but it does at least look like an easy DIY fix.

So after a morning in the workshop, how did our 144,000-mile Continental stack up? Pretty much as expected, if I’m honest: most of the Continentals I’ve driven recently have had the EML light glowing and the secondary air injection issue is a common problem with these cars.

The poor workmanship on the front strut was unexpected but shows the value of having an expert assessment and at least was easily sorted with new bolts, meaning that in the short term the to-do list is mercifully short – at least by Bentley standards.

We need to fit a new air pump and a pair of oxygen sensors, plus a set of front discs and pads, but items like the bootlid and headrest can be left until budgets and/or enthusiasm permit.