When Jaguar acquired Daimler in 1960 it also acquired the SP250, which was immediately eclipsed by the stunning new E-Type. How do the pair stack up as classics 60 years later?

Words: Paul Guinness Images: Matt Richardson

When it comes to significant events in the history of Jaguar, it takes a lot to beat the March 1961 launch of the E-Type, the car that revolutionised the Coventry firm’s sports car line-up and generated major headlines around the world. Offering super-svelte styling by Malcolm Sayer and the kind of sensational performance and driver thrills normally reserved only for the very wealthy, the E-Type became a major talking point – and was immediately hailed by many onlookers as the best-looking car of its time.

The E-Type wasn’t the only sports car being produced by Jaguar in 1961, however, as the previous year’s takeover of Daimler meant it had inherited the SP250, the V8-engined, glassfibre-bodied model that first appeared at the New York Motor Show of April 1959. Daimler was at that stage owned by BSA, founded as the Birmingham Small Arms Company but then diversifying into bicycle manufacturing in the late 1800s and motorcycles by 1910. That same year also saw BSA acquiring Daimler, which over the next five decades continued to build upon its reputation as a manufacturer of limousines and upmarket saloons.

Although Daimler’s subsequent decision to launch a sports car might have seemed odd, it was part of a two-pronged attempt to get smaller, volume-generating models on sale, including a proposed DN250 saloon, all in an attempt to return to profitability. The sports car in particular had much going for it, not least its ability to contribute to Daimler’s ‘bottom line’. Indeed, the company’s official feasibility study into the project concluded that the sportster “represents a sound technical and commercial proposition, and over a period of three years’ sales an additional profit of £747,000 will accrue to the Daimler company as a result of its introduction”.

Such optimism was suddenly in question by 1960, however, a year on from the SP250’s launch, when Jaguar acquired the financially struggling Daimler marque and with it the company’s existing model range. With the new E-Type under development, did Jaguar really want to continue producing a Daimler sports car that could provide in-house competition for the all-important Jaguar? And yet the firm was keen to stress that Daimler was safe in its hands, issuing the following statement at the time of the takeover: “Jaguar Cars Limited wishes to deny unfounded rumours to the effect that sweeping changes, including even the extinction of the Daimler marque, are to be expected.” The statement concluded that “the company’s long-term view envisages not merely the retention of the Daimler marque, but the expansion of its markets at home and overseas.”

In the end, it was the E-Type that went on to rule in the Jaguar-Daimler sports car battle, enjoying a 14-year career through three different generations and achieving total sales of 72,233 during that time. By comparison, the SP250 had managed to find just 2650 buyers by the time the very last example was produced as early as 1964, despite Daimler’s original estimates of 3000 sales annually, two-thirds of which were expected to be in the USA.

Jaguar could hardly be accused of neglecting the SP250, for in April 1961 – just a month after the official unveiling of the E-Type at Geneva – the latest B-Spec version of the Daimler was announced, bringing with it many crucial upgrades in order to answer criticisms of the early model. Jaguar chief engineer, Trevor Crisp, was quoted in Brian Long’s Daimler V8 SP250 book (Veloce Publishing, 2008), recalling his reaction to the newly inherited sports car: “Our first impression was that it wasn’t very pretty, but our main concern was to cure the extremely unrefined chassis without spending much money on it.”

Brian Long went on to describe the changes made by Jaguar in order to improve the SP250: “The chassis mods were created by Phil Weaver of Jaguar’s Experimental Department and included a three-piece hoop under the dashboard, connected through the A-posts to the sill beams. This not only strengthened the scuttle but also helped steering column rigidity. Rear uprights, or B-posts, were added to give better strength between the rear outriggers and the body, and new sill beams were added, bolted to extended outriggers.”

In his book dedicated to the SP250, Long also listed some of the bodywork and equipment changes that were introduced at the same time: “B-Spec cars carried a few very minor body alterations to give more strength and had the following items fitted as standard – full-width front and rear bumpers with over-riders, a petrol reserve and switch, screen washer unit, exhaust finishers and an adjustable steering column.”

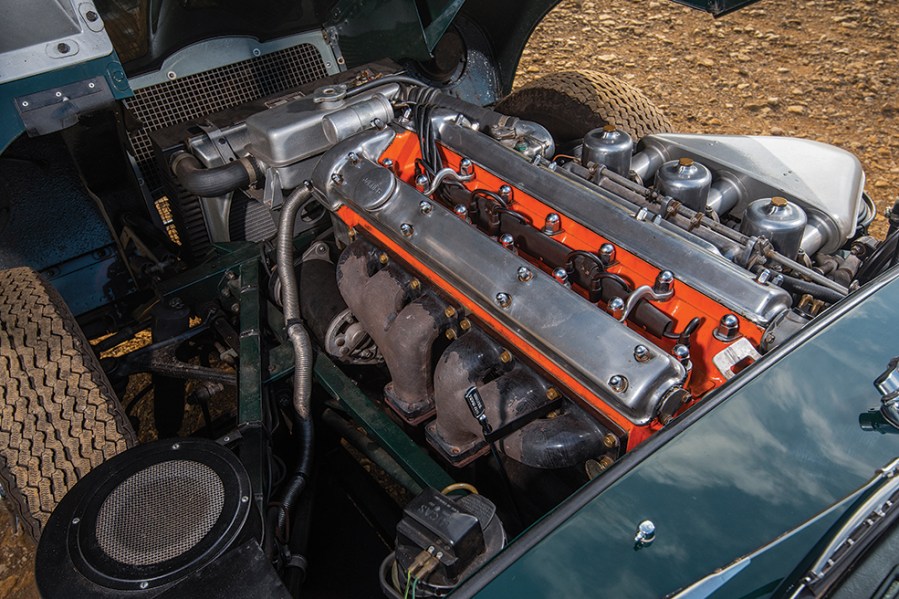

Naturally, the updated sportster continued to use Daimler’s highly praised V8 powerplant, which had made its debut in 2.5-litre guise in the original SP250 of 1959, subsequently finding its way into the long-awaited ‘compact’ Daimler saloon – the 2½ Litre V8 – that would arrive in time for the 1962 Earl’s Court Motor Show. The original idea was that V8 power would give the SP250 a boost in the American export market, where eight-cylinder cars ruled the automotive roost, ensuring Daimler had something of an advantage over British rivals like Jaguar. In the end, however, sales of the SP250 never did live up to expectations, despite the many worthwhile improvements carried out by Jaguar in 1961.

The car you see here is one of the earliest B-Spec SP250s, dating from April of that year, while the 1961 E-Type (bearing the well-known registration number, 77 RW) is historically significant for being the very first roadster produced, pre-dating the Daimler by a couple of months. Both cars can be found on display at the Gaydon-based Collections Centre of the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust (JDHT), and together they represent the fascinating choice that might have faced the potential buyer of an upmarket British sports car in 1961. The B-Spec SP250 certainly offered good value for money at £1539 in soft-top guise, undercutting the E-Type by around £500; but with the Jaguar being sleeker, more powerful and inevitably faster, did the Daimler ever really stand a chance against its head-turning in-house rival?

Although substantially more expensive than the Daimler, the exciting new E-Type’s list price of around £2000 could hardly be called excessive for what was a two-seater sports car with supercar-rivalling levels of power and performance. With a claimed 0-50mph time of 4.8 seconds and a top speed just shy of 150mph, the E-Type was by far the quickest model in its price bracket, powered by a 3781cc version of Jaguar’s highly-respected XK engine, pushing out 265bhp in its latest form.

From launch, the E-Type was available in a choice of fastback fixed-head coupé or roadster body styles, and these very early cars are now highly sought after among aficionados who value the purity of the original flat-floor design that ran until June 1962. Needless to say, with just over a year’s worth of production to its name, the flat-floor Series I is a rare beast these days, and those buyers seeking the ultimate in terms of original design and spec will pay a premium for a numbers-matching example. In the case of 77 RW, however, rarity is swapped for uniqueness thanks to this being the very first open version of all – one of just two E-Types that were used as press cars at the time of the model’s March 1961 launch.

Not only was this the first E-Type roadster built by Jaguar, it was famously driven out to Geneva in a dramatic 17-hour overnight run by Norman Dewis, Jaguar’s chief test driver and development engineer. The same car was later used by The Motor magazine for its first E-Type road test, published on March 22nd 1961, and is obviously now the oldest surviving open-top version.

For the last two decades, 77 RW has been owned by Jaguar enthusiast Michael Kilgannon, who kindly has it on permanent loan to the JDHT. The car was fully restored some years ago, with the generous assistance of Jaguar specialist Martin Robey, and these days it enjoys a cossetted existence as part of the JDHT’s vast array of cars on display at its Collections Centre.

Fortunately for us, however, the JDHT isn’t afraid to bring its cars out on to the road when the need arises (and when the weather is suitably fine), which explains how we came to encounter 77 RW when we paid a visit to the Collections Centre back in the autumn. The idea? Simply to get the very first E-Type roadster and a particularly early B-Spec SP250 side by side, not only to provide us with a fantastic photo opportunity but also to appreciate the choice faced by the upmarket sports car buyer of 1961.

Prior to the launch of the SP250 in 1959, BSA had for a long time envisaged widening the appeal of Daimler. During the 1950s, it set about developing smaller, more affordable models, the aim being to ensure a full line-up of Daimlers for greater market penetration – and part of that plan was to introduce a two-seater soft-top designed to take on the best sports cars that Britain and Europe had to offer.

If traditionalists had any doubts about the concept of a Daimler sports car for the ’60s, they would be shocked to the core the first time they caught sight of the new SP250, for the newcomer was anything but conventional. Its styling was individual in the extreme, with a thrust-forward oval chrome grille and a side profile that offered an intriguing combination of stylised curves and large tail fins. Not only that, the entire bodyshell was constructed from glassfibre (a first for Daimler), largely because of major savings when it came to tooling costs.

It’s hard to imagine more of a break with Daimler tradition than the SP250, and yet there was much to commend the newcomer. Its 2.5-litre V8 engine was a delight, for example, being powerful, flexible and wonderfully vocal all the way up to its 120mph top speed. Combine that with impressive road manners, all-disc braking and a genuinely upmarket feel, and you had a seriously desirable sporting grand tourer. Or rather, you did have once Jaguar had completed its re-engineering of the car via the new B-Spec version, following on from the firm’s acquisition of Daimler in 1960.

This particularly early B-Spec survivor – registration number 4777 JW – has been in the Midlands throughout its career, originally sold in Wolverhampton before being acquired by well-known SP250 specialist David Manners in 1974. David kept the car until 1989, when it was bought by the British Motor Industry Heritage Trust, only to be transferred to the JDHT in ’91. It was later refurbished in its original colour of Mountain Blue, albeit with red trim rather than grey, with the assistance of Jaguar’s Special Vehicle Operations department.

In 1961, each of these all-British sports cars was aimed at the well-heeled enthusiast, something that’s still very much the case now. Neither is exactly a cheap option, although the price differential between an early flat-floor E-Type in excellent condition and a B-Spec SP250 of the same age is now vast. When new, however, the percentage difference was far less, making these two machines potential rivals at the time – despite them being complete contrasts in terms of specification.

While one was a six-cylinder, all-steel, high-performance behemoth, the other was a V8-powered, glassfibre-bodied model with less power and a rather less extreme driving style. Anyone familiar with both models will appreciate this, with 77 RW still possessing that no-compromise ‘oomph’ that the original E-Type was so highly praised for. Even now, any 3.8-litre E-Type Series I in fine fettle will still impress with both its standing-start and mid-range acceleration, with its 0-60mph time (when new) of just over seven seconds putting it on a par with models costing two of three times as much in 1961. The fact that it could cover a standing-start quarter mile in 15 seconds was equally astounding, and is still hugely impressive now.

With the SP250 pushing out 140bhp when new (lagging behind the E-Type by a hefty 125bhp), it was inevitable that its performance would be rather different. Its top speed was around 120mph, and it would take just over nine seconds to hit 60mph from standstill, with the quarter mile taking the best part of 18 seconds. Driving an SP250 now, however, doesn’t feel like a disappointment, even after experiencing the outright power of the E-Type. The Daimler’s V8 powerplant is smooth, eager and happy to be worked (with the added benefit of a very appealing exhaust note, burbling but sophisticated), while its four-speed manual gearbox is slick and quick to use, enabling the keen driver to make rapid through-the-gears progress and to make the most of the engine’s impressive flexibility. Indeed, compared with the Moss four-speed manual fitted to any early E-Type, the Daimler’s gearchange is delightfully precise and refreshingly foolproof.

There was 155lb.ft. of torque on tap (at just 3600rpm) when new, and this helps to ensure that when today’s SP250 driver wants a more relaxed approach to driving, the Daimler can be relied upon to accelerate from low speeds without the need for regular down-changing. The original E-Type also had torque in abundance, of course, with a mighty 260lb.ft. at 4000rpm; but with the Jaguar tipping the scales at 2688lb (1219kg) compared with a mere 2090lb (948kg) for the Daimler, it needed that extra advantage in order to remain the performance hero.

In terms of grip and handling, both cars can be both highly impressive and downright scary depending on how experienced a driver you are. But of course, when it comes to vehicles owned by the JDHT (and particularly the world’s oldest E-Type roadster), we’re not going to push either of them to the limit for the purposes of this feature. Let’s just say that when you’re looking for a classic sportster capable of providing real driver entertainment, both the Jaguar and the Daimler will step up to the plate, despite their different approaches to sports car design.

Similarly, each cockpit is a delightful place to be, offering a low-slung driving position benefiting from a superb view of the road ahead. The E-Type’s dashboard is the sportiest of the two, but both are extremely well laid out, with clear instrumentation, logically-placed switches and an abundance of typically ’60s style. Accommodation is generous enough even for the 21st century’s burlier drivers, making both the E-Type and SP250 a reasonably practical proposition for today’s owners.

Is it really fair, however, to compare two very different sportsters such as these? After all, the E-Type has gone down in history as one of the world’s all-time favourite classics, particularly in roadster guise. It’s fast, powerful and arguably the most stylish sports car ever built. But here’s the thing: after spending a day with both of these rather special machines courtesy of the JDHT, I felt as though I’d bonded with the Daimler in particular.

Yes, I realise that not everyone appreciates the overtly eccentric styling of the SP250, and most will obviously see it as second best to the E-Type in terms of power and performance. And yet, thanks to its wonderfully flexible V8 engine, this is a car with real talent and its own take on driver appeal. Its glassfibre bodywork is practical, its standard of finish (in B-Spec guise) is good, and its driving experience is quick enough and capable enough to inject some proper old-school enjoyment into any long-distance adventure. Thirty years ago, I perhaps struggled to see beyond the car’s aesthetics, yet even these have grown on me as I (and the car) have aged. I suddenly have a new-found respect for the SP250, the model that brought open-top motoring and V8 power to the Daimler line-up – and which nowadays offers vastly better value than any ’61 E-Type. It’s a funny old world.