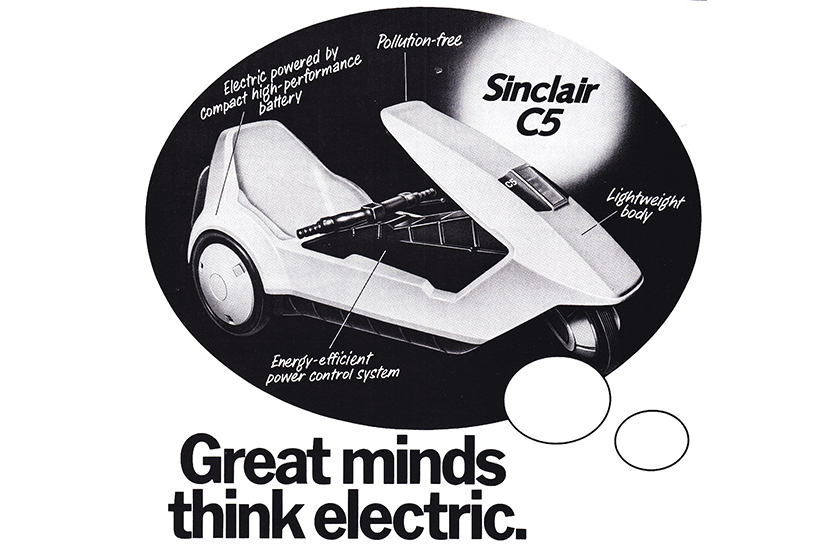

Thirty-three years on from its launch, Paul Guinness considers whether the much-maligned Sinclair C5 could have been the start of something big for its innovative creator…

Electric vehicles are gradually becoming more mainstream, with increasing numbers of different models now available in the UK – ranging in price from just under £7000 for the quirky Renault Twizy through to the best part of £140,000 for a top-of-the-range Tesla. Intriguingly though, one of Britain’s most famous inventors and entrepreneurs saw potential in the electric vehicle market as far back as the mid-1980s, famously launching the single-seater Sinclair C5 almost exactly thirty-three years ago.

Yes, it was on January 10th, 1985, that computer expert Sir Clive Sinclair unveiled his battery-powered trike at London’s Alexandra Palace, confidently predicting that more than 100,000 examples would be built and sold each year. But in the end the project was short-lived, with production ceasing after just seven months due to poor sales and unsustainably high stock levels. Sinclair Vehicles found itself in receivership by the October, which leaves one obvious question more than three decades later: did the Sinclair C5 really deserve to fail?

These days, the much-maligned C5 has something of a cult following, with displays in various museums (including the National Motor Museum at Beaulieu) and a thriving owners’ club (at www.c5owners.com) to its name. Maybe that’s not too surprising, given that many Brits love oddballs and historic failures in equal measure. But it must still frustrate 77-year-old Sir Clive Sinclair that his vision of low-cost electric transport failed so spectacularly.

It’s easy to see why Sinclair saw merit in his idea. With even the cheapest new car – the Fiat 126 – costing £2184 at the time of the C5’s launch, surely an electric-powered single-seater with ultra-low running costs would find its own market at a list price of just £399? Sinclair charged an extra £29 for direct delivery to your door, but even so the C5 worked out at less than a quarter of the price of even the most basic new car.

The problem, however, was that the C5 came with none of the things that car buyers took for granted. Like a roof. And bodywork. And the ability to travel reasonable distances. Battery technology of the ’80s was far less advanced than it is today, with the C5’s lead-acid battery providing a claimed maximum range of just 20 miles (though many owners reported this could be as little as 10 miles, particularly during cold weather). You could, of course, pedal your C5 once its batteries had gone flat, but where was the fun in that?

The C5 driver was also exposed to the elements in a way that even motorcyclists weren’t familiar with (remember, the law didn’t require a C5 owner to wear a helmet), the only protection from British weather conditions being Sinclair’s optional fabric side panels and raincoat. And another issue was the fact that the C5 driver sat close to the road, making them even less visible than a cyclist in urban situations. Sinclair hit back by claiming that a C5 driver’s head was actually higher than that of a Mini owner – though, of course, the driver of the Mini didn’t have to endure a face full of exhaust fumes at every set of traffic lights. Perhaps surprisingly, safety charity RoSPA declared in 1985 that the Sinclair C5 was in fact perfectly safe on the road, but this endorsement wasn’t enough to give sales a boost.

The C5 as a project was interesting enough to attract some household names when it came to design and construction. Lotus lent a hand with its development and testing, whilst Hoover created a bespoke new manufacturing centre at its facility in Merthyr Tydfil. But the C5 got off to a dreadful start even at its press launch, with several examples failing to move for the assembled journalists. It received lacklustre support in the press, with the Sunday Times referring to it as a ‘Formula One bath chair’.

The failure of the C5 to capture the public’s imagination came as a bitter disappointment to Sir Clive Sinclair, who’d seen real potential in a battery-powered trike with a top speed of 15mph and the ability to be legally driven on the road by anybody aged 14 or over. It was, he insisted, the perfect solution to the problem of personal mobility in urban environments. So thirty-two years later, should we concede that Sinclair had a point? With congestion on our roads worse than ever, and with increased concerns over vehicle emissions, perhaps a rechargeable, affordable single-seater isn’t the daftest idea in the world.

Writing for Management Decision in 1990, however, industry expert Andrew P Marks gave his own views on the C5’s failure: “Sinclair ignored the basic principles of marketing and new product development, and thereby made a number of fundamental errors. The market was badly defined, there was a lack of both quantitative and qualitative market research, [and] the safety and performance aspects of the vehicle failed to meet the manufacturer’s claims.”

In the end, just 14,000 C5s were manufactured, with almost a third of that total remaining unsold when Sinclair Vehicles went into receivership. The much-maligned trike’s headline-grabbing failure came as no surprise to its most vocal critics. And yet I can’t help feeling just a little sad that Sinclair – a phenomenally successful IT innovator during the early days of home computing – failed in his quest to provide an affordable electric vehicle.

The C5 was, of course, the wrong product launched at the wrong time. Had it succeeded, however, it might have paved the way for future electric cars from Sinclair, of the type we’re now starting to see on our roads via other manufacturers. Who knows, success for the C5 could have brought a whole family of Sinclair electric cars to market, three decades before Elon Musk managed to launch the very first Tesla in 2008. But it was not to be… and the C5 is still seen by many as something of an automotive joke, albeit without much of a punchline.