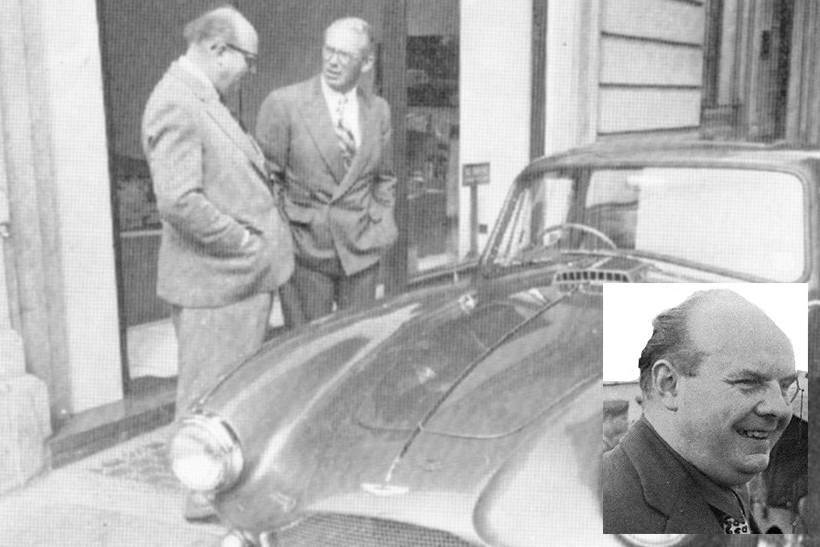

Jeremy Satherley recalls a motoring character whose views belied his appearance. A certain Laurence Pomeroy Junior…

It occurred to me the other day that with the passing over the years of learned motoring scribes such as Michael Sedgwick and L J K Setright, we’re getting rather short of ‘intellectuals’ on the motoring scene as a counterweight to the ‘Clarksons’ of this world.

Another automotive ‘don’ was Laurence Pomeroy Junior, who entertained us with Jeeves-like verbosity into the ’Sixties on the pages of the long-defunct The Motor magazine.

His credentials came copper-bottomed, for he was the son of Laurence Pomeroy Senior, who as a young man made Vauxhall’s name in 1908 with his design (ready in only six months) for a 20hp three-litre car that won the RAC 2000-Mile Trial. The legendary Vauxhall 30/98 was also Pomeroy Senior’s work before he progressed to managing director of Daimler, finally weaning the Coventry firm off sleeve valves and highly-complex V12s in favour of conventionally-valved straight-eights. But Pomeroy Junior, though also trained in engineering development work and elevated to the Society of Automotive Engineers, favoured journalism as well as the drawing board and served from 1936 to 1958 as The Motor’s technical editor.

To look at, Pom could have walked straight out of a novel like Brideshead Revisited. Resplendent in monocle and quality tailoring, a Rolls-Royce was a “Royce”, lunch was always “luncheon” (his ideal of a ‘gentleman’s’ motoring picnic included a couple of grouse and a half-bottle of Cointreau) and his writings were full of phrases like “in acceleration it is manifestly inferior thereto”, or “the opportunity was vouchsafed to give a close comparison”. In fact, he never used few words when double that amount would do, so we got “two lamp bulbs represent the only toll which has been demanded by Mr Lucas” instead of “two Lucas lamp bulbs were the only replacements”. It would have reduced today’s sub-editors to tears.

But behind the waistcoats and watch chains was a character who became a Mr Toad behind the wheel. He was as happy as Larry with his lovely MG SA 2-Litre Tickford drophead delivered in 1937, and was enraptured with its Philips radio, on which he could pick up Hitler’s Anschluss rantings, or his beloved BBC Symphony Orchestra. This car could do no wrong. Even when ‘a big end became slack’ at 30,000 miles, it was his fault, not the car’s.

A great supporter of minimalist motoring, Pom came up with proposals for a front-wheel drive small car in 1939 with a transverse, 600cc engine and room for three on the front seat and one behind. If war hadn’t got in the way, one wonders what would have resulted. Post-war, he played a part in Jowett’s liaison with ERA and the invitation of ex-Auto Union chief engineer Eberan von Eberhorst to develop the sporting Jowett Jupiter. Meanwhile for the past 61 years the VSCC Pomeroy Trophy event at Silverstone has existed as ‘a brilliantly simple set of driving tests run to a brilliantly complex set of rules’ – in other words, a competition typical of the man. His books, The Grand Prix Car volumes I and II (covering the 1906-1954 period) are now revered and costly collectors’ items, as is The Design and Behaviour of the Racing Car, co-written with Stirling Moss.

Pom’s hack for many years was a tuned 1953 MkI Zephyr with a boy-racer Alexander Extractors twin-tailpipe extension, enabling him to chase 220SE Mercs on the autobahns, or tear up the new M1 at ‘100-106mph’. By 1961 he was singing the praises of the Simca Aronde’s power unit: “If I had my way, all four-cylinder engines would have five-bearing cranks”. But a hairy press day at Montlhéry in an understeering Peugeot 404 left him quite shaken. “I fear I cannot be reckoned a member of the 404 fan club”, he said afterwards, “but I am conscious in this matter I stand like Athanasius” (for us uneducated blokes, he was a bishop of Alexandria exiled for 17 years by four Roman emperors).

Yet that other Farina-styled contemporary, the Riley 4/68, really impressed. He simply loved those tail fins! “I personally would like to see them much larger”, he said, “as I am wedded to the formula of providing low-speed dynamic oversteer, which is mastered by aerodynamic understeer at high speeds”.

In 1962 – four years before he died, at only 58 – he treated himself to a stately 1950 Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith, which with its deep-sided H J Mulliner body and majestic Lucas P100 headlamps, seemed much more in tune with his image. While friends thought it an extravagance, it “crowned a lifetime”, he said, “in which I have been continuously suspended over the abyss of bankruptcy by the cantilever of credit”.

But affordable or not, it was surely this inimitable man’s just reward.