Paul Guinness mourns the apparent decline of the family estate car…

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the Matra-Simca Rancho, something that will probably only interest those who are fanatical about all things oddball and French. Using the front end of the Simca 1100-based pick-up and equipping it with a boxy glassfibre rear end, a raised ride height and lots of faux 4×4-like adornments (but not all-wheel drive itself), the Rancho was seen as a unique offering upon its launch in 1977.

To the casual onlooker, the Rancho looked like a cut-price Range Rover rival (and even adopted that model’s horizontally-split tailgate style), and yet its actual off-road ability was poor thanks to its lack of four-wheel drive. The Rancho proved reasonably popular in its homeland but struggled to find a niche in Britain, where potential buyers were perhaps confused by the notion of a front-wheel drive off-road lookalike. And yet, four decades later, we should perhaps view the Rancho as one of the most significant newcomers of the 1970s.

Not significant because of its sales success, of course. (With just 57,792 Ranchos built during a seven-year career, it was a big deal by Matra standards but pretty insignificant in terms of the mass market.) But there’s no doubt that the Rancho was a true trendsetter, a vehicle that effectively created a whole new genre that is now – four decades later – attracting vast numbers of buyers worldwide. In the UK in particular, SUVs and crossovers are massive news, with a large proportion of them being ordered with two-wheel drive only.

It’s easy to see the appeal, even if the buyers of 1977-84 (the lifespan of the Matra-Simca Rancho) couldn’t grasp the concept. With an SUV or crossover you get easy access and a commanding view (these vehicles sit higher than a conventional car), decent luggage space and a practical interior full of storage innovations. Arguably just as important to many of today’s buyers, however, is the fact that you get to be seen driving the latest in automotive styles, proving to the world that you’re a trendsetter. Or something like that.

Naturally, some of today’s SUVs come as standard with all-wheel drive, giving them at least a touch of rough-stuff ability and extra grip when towing a caravan across a muddy field. That’s why you can’t buy a Land Rover Discovery or a Range Rover without four-wheel drive, as it’s an integral part of each model’s DNA. And yet… and yet, how many old-car folk realise that the Range Rover Evoque can be ordered in two- wheel drive guise? Perhaps we shouldn’t be too surprised, given that the Evoque appeals more to fashionistas than farmers.

Away from Land Rover, and looking at the ‘compact SUV’ sector in particular, two-wheel drive certainly rules the roost. I remember reading some time ago that 95% of all first-generation Nissan Qashqais sold in Britain were two-wheel drive. And despite the fact that MG’s first ever SUV – the new GS – is available in its Chinese homeland in both two- and four-wheel drive spec, it’s sold in the UK purely as a front-wheel drive model. Oh, and if you go looking for a Vauxhall Mokka, Ford EcoSport or Renault Captur with four-wheel drive, you’ll find the cupboard’s well and truly bare.

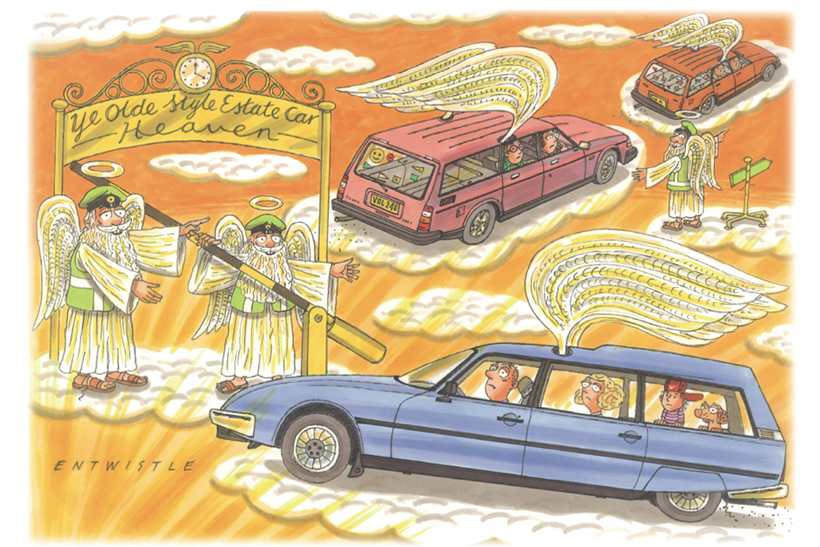

There was a time, of course, when anyone needing a family car with maximum versatility would automatically buy an estate. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, the estate was the vehicle of choice for private punters and company car drivers alike who demanded lots of space for people and their belongings. And, I must admit, I’ve always had a soft spot for the traditional estate, a design that sometimes even manages to be rather good looking; to my middle-aged eyes, classic estates as disparate in design as the Volvo 240, Ford Sierra and Citroen CX are still aesthetically very pleasing.

You knew where you were with an estate. You got the familiar driving style of whichever saloon it was based on, combined with a load- swallowing tailgate, a decent boot area, and the ability to accommodate a wardrobe with ease once the back seat was folded flat. The traditional estate wasn’t trying to be over-clever; it simply offered a practical car-based solution to everyone’s load-carrying requirements.

The first threat to the estate came with the 1980s arrival of the multi-purpose vehicle (MPV), a trend that began with the Renault Espace. But in the 21st century even the MPV has become more SUV-like, as the latest models from the likes of Peugeot and Renault confirm. From the world’s two biggest car markets of China and the USA through to just about every European car-buying nation, the SUV genre is what every major manufacturer is desperate to expand into. And once you have sporting brands like Porsche, Jaguar, Maserati and Alfa Romeo either producing or planning entire families of SUV models, you know there’s still more growth to come.

How long the SUV trend will last, nobody can predict with any degree of certainty; the current signs are that it will continue to grow for several years to come. But where does that leave the poor old estate car, a model that seems almost old-fashioned as a concept if we’re to believe the current SUV hype? It’s certainly the case that we see more Mokkas and Tourans on our roads than we do new Astra or Golf estates, which suggests that the estate car sector is in decline. And as an estate fan, this saddens me.

As much as I admire the ingenuity shown by Matra when it created Europe’s first two-wheel drive SUV/crossover way back in 1977, I’m disappointed that 40 years later manufacturers are adopting the approach en masse – and effectively killing off the traditional estate in the process.

There are pockets of hope, of course, with excellent (and rather handsome) estates like the latest Volvo V90 and Skoda Superb keeping the upper end of this long-established sector ticking over; and yet it’s inevitable that the latest Kodiaq and XC90 from the same two manufacturers will be far stronger sellers. The estate car may not be dead, but its importance to most potential buyers is currently at an all-time low. And I can’t help feeling that’s a real shame.