Paul Guinness recalls the days when Japanese cars were frowned up by the classic car fraternity…

I’m not particularly proud of the fact that I currently have a lease car for my daily transport needs, a supermini-size model that’s built in the Czech Republic and has been totally fault-free for almost eighteen months. I won’t bore you with the details (make, model, that kind of malarkey) as… frankly, like so many other new cars… the entire experience of custodianship has been deeply uninteresting. It’s due to be collected in early July, at which point I’ll be returning to the never-a-dull-moment world of bangernomics.

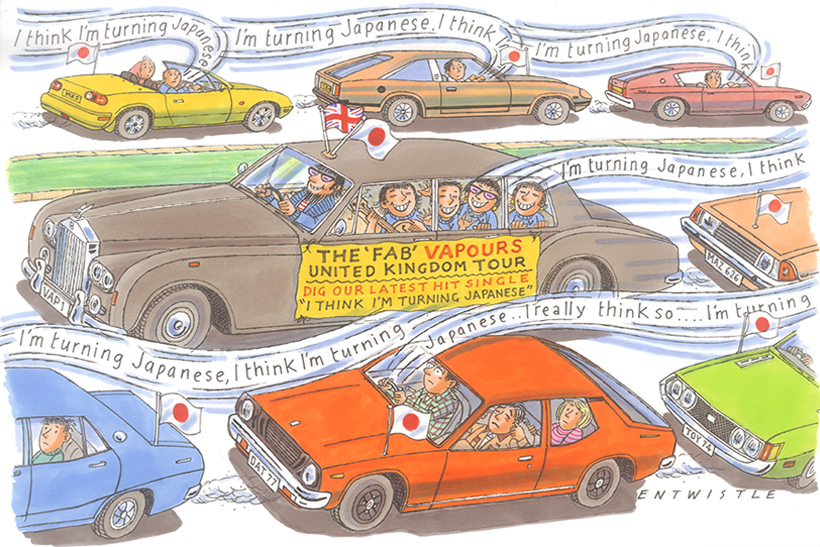

One thing I have enjoyed, however, is my lease car’s DAB radio. It has allowed me to listen to all sorts of minor radio stations I’d otherwise have missed out on with a basic FM-type set-up. And it was one of these stations I was tuned into a couple of months ago, when I was suddenly transported back to 1980. (Not literally, as that’d be ground-breaking news; but you know what I mean.) Suddenly, over those DAB-tuned airwaves, came a song by The Vapours, first released in 1980 (when I was a typically strange 15-year-old) and entitled ‘Turning Japanese’.

You probably know the song. And even if you’ve only ever heard it once, there’s every chance it’s hidden away somewhere in your brain, threatening to pop into your conscious thought at any moment. The combination of simple chorus lyrics (“I’m turning Japanese, I think I’m turning Japanese, I really think so”, repeated incessantly) and an addictively repetitive tune makes it one of the most annoyingly memorable singles of its time. Quite simply, it can never be forgotten, no matter how hard you might try to erase it from your memory.

Since hearing The Vapours’ best-known song once again, I’ve coincidentally found myself writing extensively about Japanese cars – and what might loosely be called Japanese classics in particular. And this is an interesting development, as I can readily recall the days when almost anything wearing a Japanese manufacturer’s badge was either sneered at or ignored by the majority of classic car enthusiasts. Times have changed, of course, and these days there’s no shortage of Japanese-built models that are highly sought after on the classic scene, which in turn has an effect on the world of niche publishing.

There’s a sister title to Classics World going by the name of Retro Japanese, and it’s really rather good. I would say that, of course, as I tend to be a regular contributor to it these days; but even looking at it through non-biased eyes, it’s surprising just how many different cars from Japan are now appreciated by British enthusiasts. A Datsun Cherry 100A or Sunny 120Y from the 1970s might have been laughed at by classic traditionalists a few years ago, but any survivor in decent condition will now draw crowds at a show. The models that started the Japanese sales revolution more than four decades ago, and which used to be a regular sight in just about every town up and down the land, have finally been accepted into the classic mainstream.

CHANGING TIMES

Of course, one or two of the more specialised Japanese models have always had their British followers. Even back in the 1980s, when just about every other old car from Japan was being ignored, journalists and enthusiasts alike would heap praise on the Datsun 240Z and Honda S800 of the late ’60s. These were the Japanese models that, thanks to their forward-thinking engineering and all-round brilliance, have always been admired by Brits, and rightly so; but until relatively recently, they were the rare exceptions.

So what is it that’s changed? Why has ownership of a Japanese classic suddenly become desirable, even something to aspire to? In the case of the ’70s saloons mentioned earlier, it’s probably down to little more than the passing of time; as they get older and the number of survivors dwindles, enthusiasts who appreciate something different suddenly realise that an old Datsun or Toyota can be a sensible classic option. Few people would claim that an early Sunny or Corolla is technically interesting, but a combination of rarity and usability gives them some 21st century appeal.

The modern-classic scene is different, though. This is where the upsurge in interest is surely down to the way in which Japanese cars not only improved from the 1980s onwards, but also began filling automotive niches. Crikey, it was the Japanese (or rather, Mazda) who effectively re-launched the classic two-seater roadster thanks to the 1989 arrival of the MX-5 – which, over successive generations, has become the best-selling sports car of all time. Throw into the mix a plethora of Japanese sporting coupes proudly bearing such monikers as CRX, MR2, 200SX and RX-7, and you have some stylish Japanese temptations on offer.

The Japanese even jumped on the super-saloon bandwagon of the 1990s, with newcomers like Subaru’s Impreza 2000 Turbo and Mitsubishi’s Lancer-based Evolution combining all-wheel drive and turbocharging for the ultimate in rally-winning behemoths. The same decade saw Toyota pushing further upmarket through its Lexus luxury division, while Honda wowed enthusiasts via its VTEC technology and its various Type R derivatives.

All these years later, a whole new generation of classic enthusiasts is appreciating this engineering excellence. They’re not bogged down by the prejudices of old, and instead see their modern-classic Japanese cars for what they are: exciting, innovative and very rewarding to drive.

Meanwhile, I’ve just finished writing a feature for a general modern-classic magazine on the second-generation Honda Integra Type R, which wasn’t launched until 2001, was never officially sold in the UK, and yet now has a loyal following among enthusiasts who’ll happily spend £10,000-plus on a low-mileage grey import. And all the while I was writing it, that damned song by The Vapours reverberated around my head, annoying me with its repetitiveness, frustrating me with its bloody stupid lyrics. I fully ‘get’ the appeal of a Japanese classic, whether it’s fifty or fifteen years old; but the downside of their popularity is my brain’s refusal to let go of that tune from 1980 every time I’m asked to write a Japanese car feature. Is there really no escape?