Nigel Stennett-Cox looks back on a name he fears long forgotten – that of William Morris, and the rags to riches story of one of Britain’s greatest philanthropists…

Maybe the title is a little blunt, and should be qualified by saying something like, ‘real car people.’ Your columnist is thinking of ones who, maybe from bicycle or motorcycle manufacturer origins, began and went on to lead vehicle manufacturing firms that became household names.

They tended to originate in the nations which led the field in car production and design; France, Germany, Britain and the USA. Sadly, the companies they founded sometimes folded or went through painful transitions when the founders succumbed to the vagaries of advancing years.

One such would be the Ford Motor Company, nearly going under during the period spanning 1945-1948, but pulling through with the Herculean efforts of the founder’s grandson, Henry Ford II, and his team. Even Karl Benz insisted upon hanging on to his original belt- drive design for long enough for it to have become so outdated by about 1901 as to drag the company down but not, fortunately, out. Another once highly successful company closer to home to suffer a more final fate was the Rootes group, faltering and then succumbing to a take-over just before the death of William Rootes in 1963, followed by his brother Reginald shortly afterwards.

One British pioneer upon which your writer would like to focus is William Morris, the later Lord Nuffield, whose manufacturing empire grew to become the biggest in Britain to not be foreign-owned by the mid ‘Twenties, and made him a millionaire so many times over that his charitable donations were colossal, particularly to medical charities. This writer fears that few nowadays realise that the medical institutions still around today bearing ‘Nuffield’ in their names owe their existence to one who started out as an Oxford bicycle repairer.

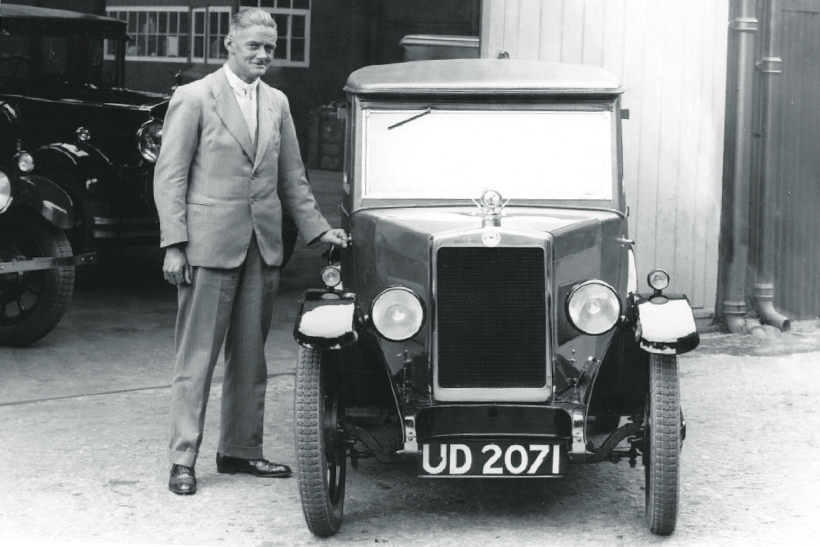

Born in 1877 to a farm manager, Morris started bicycle and later motorcycle production in addition to his repair business. By 1910 he was well-established in these fields. Morris began to design and put together an ‘assembled car’ in 1912, with production of the Morris Oxford starting in early 1913. The term ‘assembled’ meant that all major parts were bought-in from specialist component manufacturers, mostly in that cradle of the British Industrial Revolution, the West Midlands and Black Country. Engines came from White and Poppe, gearboxes and differentials from Wrigley, and the ensuing little car with its distinctive bullet-nosed or bullnose radiator achieved instant popularity. Luck, or more likely good judgment, resulted in a small and reasonably-priced car being just what the emerging motoring middle classes wanted, especially when powered by a proper water-cooled four-cylinder engine.

Like his counterpart Herbert Austin, Morris was keeping a keen eye on progress across the Atlantic, even if both were loath to admit it, and had seen how Ford was expanding phenomenally by increasing production and seeing unit costs tumble. Morris simply put another step in this equation and, by not manufacturing components himself, put in huge and increasing orders to his suppliers while bringing the offered price down and so forcing the suppliers to bring in production economies. The frequent next step was to buy out the suppliers when they were in the weak position of his being their biggest customer, thus leading to Morris becoming a full-on manufacturer. The latter happened to the still extant S.U. Carburettor Company, or Skinner Union.

In 1915, Morris switched to buying the excellent Red Seal engine from the Continental Company of America but German U-Boat action sent one load of these to the bottom of the sea. After the war, Morris took a Continental engine to the French engineering firm of Hotchkiss’ Birmingham branch and asked them to copy

This they did and they also later became Morris [Engines] and thus it became that right up to after the Second World War that all Morris engines were built to metric dimensions, threads included. But to keep the garages and owners happy, the heads and hence spanner sizes were to Imperial (Whitworth) standards.

The early ‘Twenties saw meteoric sales rises and diversification into commercials, this latter seeing the formation of Morris-Commercial Cars, which later made bigger and more specialised lorries, and even bus chassis right up to its Imperial double-decker in the early ‘Thirties. Then MG grew from the Morris Company’s garages branch and the pioneering firm of Wolseley was taken over in 1928. Riley came into the fold ten years later; an unsuccessful foray into radial aero-engine production also being undertaken in the ‘Thirties. A lack of contracts rather than any problem with the engines themselves seems to have been the cause.

The pre-Series, Series I, Series II and Series E Morris Eights established themselves as the best-selling single model of car ever produced by the pre-war British industry. About as many, just shy of 300,000, were produced as Austin Sevens, but in about a third of the time in production.

By the time of the Second World War, Lord Nuffield (as he then was) with the name taken from the village near Oxford where he lived, was probably at his professional peak. Legend has it that he had been refused permission to join the local Huntercombe Golf Club because of being in ‘trade’ rather than a landowner or professional, so when it came up for sale, he bought the lot, no doubt seeing off anyone who had been part of the earlier decision.

Alas, his much-publicised lack of apparent success as chief of aircraft production early in the war might have marked the beginning of the decline which eventually catches up us all. He seems to have been unenthusiastic about the Morris Minor design of Alec Issigonis in 1948, likening the shape to that of a poached egg, but lived to see its production pass the million mark in December 1960. Morris, or the Nuffield Empire, by then producing successful tractors under the Nuffield name, had merged with the Austin Motor Company in late 1952.

This latter move resulted in widespread badge-engineering, with the always mass- market Morris name not carrying high status despite being very well-known. William Morris died in 1963, the Morris name happily not in serious decline by then, but, as we all know, when the last Ital left the line in 1984 it was little-mourned…