3D printing of spares has long been heralded as a solution to sourcing scarce historic vehicle parts. Problems sourcing safety critical components – brake calipers and bottom arms, for example, has long been a concern of lobbying groups like the Federation of British Historic Vehicle Clubs (FBHVC) and its stakeholder clubs.

Porsche Classic recently raised the bar when it announced it had reproduced nine out-of-production parts by 3D printing. These components, available from its parts catalogue, include a clutch release lever for the 959 supercar, and exhaust heat exchanger brackets for the 356 B and C; 20 more parts are planned for release in the near future.

For metal items, Porsche uses selective laser melting (SLM) to layer up powdered steel onto a plate – a light beam then melts the powder to the required shape.

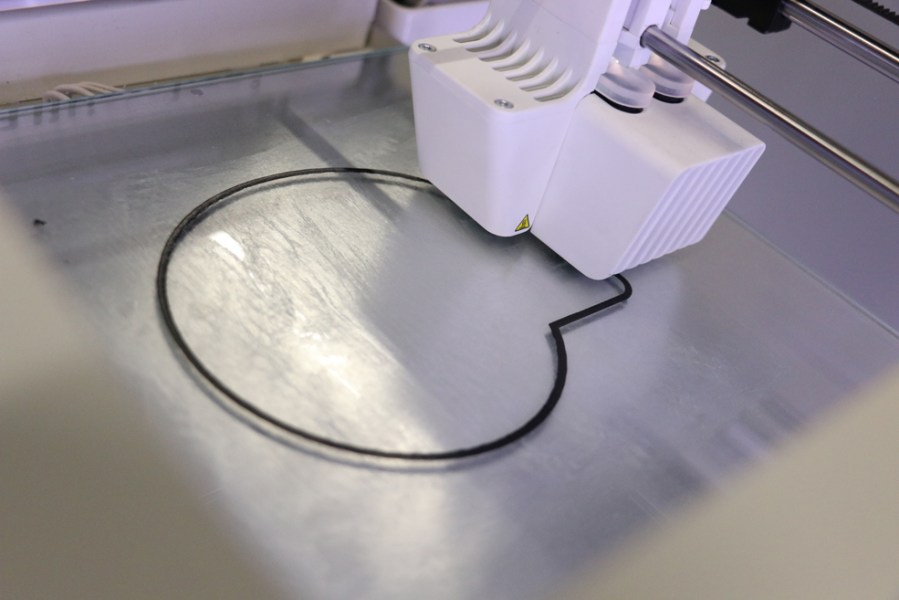

In terms of plastic parts, selective laser sintering (SLS) is used, whereby the material is heated just below melting point and a laser moulds the material to the desired shape required.

In each instance, the new parts can be tested and guaranteed to the same standards as the originals, a crucial step in meeting the shortfall for safety critical parts.

Both processes are common in high-level motorsport – like Formula One teams, which often need to take prototype parts from computer screen to track in a very short time frame.

The costs involved are massive; top-tier F1 teams can amortise the cost of the equipment and raw materials as part of their budget.

Eventually, the technology trickles downward to those road car manufacturers with the necessary financial fortitude; Mercedes Benz Trucks and Bugatti use similar technology when replenishing their spares supply. Porsche Classic’s programme is one of the first instances of 3D printing being used to feed the historic vehicle spares market – and its customers have the money to pay for spares as and when required. The 959, of which 292 were built, fetch seven figure sums on the rare occasions they appear; six figure asking prices for good 356s are not unheard of.

A spokesperson for Porsche GB said: “Every single Porsche is part of our family and history. 70 per cent of all Porsche cars ever made are still on the road and we care passionately about keeping them that way. More than 50,000 parts are available over the counter to purchase from Porsche Classic for a variety of different models. New developments such as 3D printing allow us to expand this range further still. We recommend qualifying owners sign up to the Porsche Classic Register via – this way they can be kept updated on new introductions.”

Porsche Classic’s inclusion of 3D printed parts to its roster prompted excitement from elsewhere in the classic car community.

Jaguar specialist SNG Barratt added a 3D printer to its workshop last year; it currently relies on injection moulding and traditional casting methods to produce plastic and metal components.

“It all depends on the part in question and its application,” explained SNG’s Design and Quality manager Charlie Ralph. He continued: “We’re currently using [our 3D printer] as a prototyping tool to check the form and function of some of our parts that have quality control issues. The printer that we invested in does have the capacity to print ‘real-world’ plastics. The next step (which we are currently looking at right now) is to print some actual production parts and integrate them into some assemblies and possibly our individual component stock (pending testing and feedback). We’ve seen great success with the prototyping side so now we want to see where we can go with production parts and play about with the different materials on offer.”

Rootes Centre Archive Trust’s trustee Andy Bye was similarly optimistic about the future of 3D printed spares. “It’s an exciting period for classic car owners. Within the next five years, the cost of the technology will fall to the extent that cottage industries, clubs and individual owners will be able to produce their own replacement parts. The benefits are there an industrial scale, and the parts can be guaranteed. ”

Like Porsche Classic, which also offers hard to find trim pieces in its spares catalogue, Rootes Centre Archive Trust benefits from having the original engineering drawings – half a million of them, from bezels to bodyshells-in-white – housed inside a scratch built archive (which will open to the public on Drive It Day, Sunday, April 22). We wouldn’t be interested in producing spares; we’re happy to be the custodians of the knowledge, because it simplifies the process for our chosen suppliers.”

Andy added. “Once you have the drawings, SLM or SLS 3D printing makes things even easier. It avoids the need for costly reverse engineering and encourages people in the UK to produce parts. We can improve on the quality and accuracy of new-old spares; it’s a series of developments we’ll be watching with great interest.