Bespoke coachwork on ordinary cars was normal in the vintage era, but the 50s Austin A40 Sports didn’t have success with the same recipe. But why not?

By the start of the 1950s, the Austin Motor Company was in a fairly comfortable position. In 1941, with the firm busy with munitions and other war work, founder Herbert Austin had passed away aged 74. With no heirs, that left managing director Leonard Lord in effective sole command of the company, a position which was formalised in 1946 when he was made chairman. With his customary drive, and with the somewhat restrictive influence of Herbert Austin now out of the picture, Lord was determined that Austin should steal a lead over its rivals in not only resuming civilian car production but launching new models.

The day after VE Day (May 8, 1945) Austin launched the all-new Sixteen, a large, rugged saloon that had been on the drawing board since 1939 but now benefited from a brand new 2.2-litre overhead valve engine of highly modern design. The smaller Eight, launched in the last days of peace in 1939, had remained in slow production during the war for military use and was switched back to civilian production alongside the launch of the new Sixteen.

Behind the scenes Lord was overseeing an all-new range of post-war Austins. Well aware that there was a global demand for new cars and that government policy would require British firms to concentrate on exports, he eschewed a small car and plumped for a two-model range of a mid-size vehicle and a large one to replace the Sixteen. While the British motor industry wouldn’t officially ‘open for business’ until the London Motor Show of October 1948, Austin’s new cars were already rolling out of Longbridge and heading overseas in 1947. These were the A40 (sold in two-door ‘Dorset’ and four-door ‘Devon’ saloon versions) and the A70 ‘Hampshire’).

The tight time schedule imposed by Lord meant that they were a curious mix of the old and the new – they certainly weren’t a patch on the advanced new range of Morris cars introduced in 1948. They sat on traditional separate chassis, had pre-war cam-and-peg steering and indifferent hydro-mechanical brakes. While they did boast independent coil-spring front suspension their road manners were uninspiring. Even in the car-hungry and patriotic world of the 1940s their cautious engineering attracted criticism.

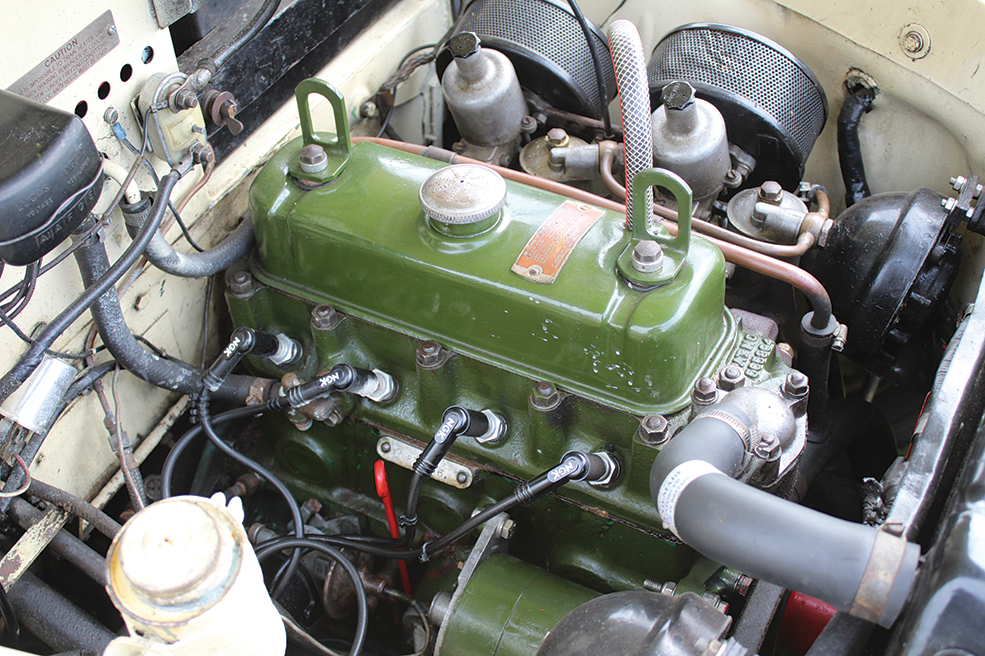

But they had upsides. All had superb, refined and efficient overhead-valve engines – the A70 retaining the 2.2-litre unit from the Sixteen and the A40 having an all-new 1.2-litre unit along the same lines. Their curvaceous styling, worked on jointly by Leonard Lord and ex-Lancia designer Dick Burzi, was a scaled-down tribute to the latest American cars and was bang up to date to inject some welcome glamour to the austere post-war years. Besides that the Austins were much more modern than the ageing pre-war cars then on the roads and proved to be good, reliable machines.

What they were not, at least to car-starved British drivers, was available. Manufacturers like Austin were required to send at least three-quarters of their production abroad – a benchmark Austin comfortably exceeded. Rationed fuel, high purchase taxes and covenants forbidding selling-on, as well as generally straitened economic times, deterred domestic buyers from buying an A40, especially when the Morris Minor was cheaper, more economical and much more modern to look at and to drive. In 1948 fewer than 80 Austin A40s were sold in Britain and in 1949 that climbed to only a few hundred. Not that this concerned Leonard Lord, since Austin’s sales figures and production numbers were setting new records as buyers almost everywhere except Britain took to the new cars.

American dream

The place that all the export-hungry British car makers had their eye on was the USA – a newly-risen economic superpower with a booming economy and a thirst for cars. Lord had not neglected the American market. The initial Austin range included the fantastic A90 Atlantic, a two-door coupe/cabriolet version of the A70 with extravagant styling aimed directly at American tastes. Lord had set up an American subsidiary for Austin with its headquarters in a New York but the Americans almost completely spurned the apparently tailor-made A90 – of the 8000 built fewer than 400 were actually sold Stateside.

The real British motoring success in America was the MG T-type sports car, produced by Lord’s erstwhile employer (and now nemesis), Morris Motors, which was quickly joined by the upstart Jaguar XK120. It proved that what the Americans were willing to buy from Britain were cars with a sporty character and European style, but Austin had nothing to offer.

Fortunately the solution lay in the Austins’ conservative engineering – because they were built on a chassis, it would be practical to drop a restyled, sporty-looking body onto the same running gear for very little cost.

There was an obvious way to achieve such a things too, as Austin was supplying the A70’s chassis and the engine and transmission of the Sheerline limousine to Jensen Motors of West Bromwich to building up into an unmistakably European-looking grand tourer called the Interceptor. This carried a Jensen-built body styled by a former Austin employee, Eric Neale.

With the relationship between Jensen and Austin already well-established, it was easy for Lord to arrange for Neale to scale down his Interceptor design to fit on the A40 chassis to provide Austin with the sporty, stylish car that it needed. With Austin’s considerably greater resources, the new car, dubbed the Austin A40 Sports, was unveiled to the public before the Jensen which inspired it – the Austin was announced at the 1949 London Motor Show, a year before the Interceptor met its public for the first time.

However there was a delay before Jensen could provide Austin A40 Sports bodies in sufficient quantities for production to begin, so Austin A40 Sports sales didn’t actually start until the winter of 1950. In fact the design of the new A40 was signed off before Neale’s design for the Interceptor was properly ‘settled’, so he was able to use lengthened versions of the doors built for the Sports on the larger car.

Despite its name, the Austin A40 Sports had little in the way of mechanical changes or performance upgrades over the standard A40 Devon. The 1.2-litre engine did have a second carburettor, taking power from 42 to 46bhp, with a more useful increase in torque. There was a floor-mounted gear lever instead of the Devon’s column-shift, and the two chassis rails under the centre section had sheet metal added to create a large box section to improve the car’s rigidity. The suspension, steering and brakes were unaltered, meaning that there was little sportiness to the new model’s character.

However there was no denying the car’s greatly-improved looks. It was, if anything, prettier than Neale’s original design for the Interceptor, while the body and cabin of the Austin A40 Sports was built and trimmed to a high standard and the car was praised for the quality of its materials and build.

Sales struggle

The coachbuilt body and low-volume exclusivity did come at a price, as the Austin A40 Sports cost £818, or £300 more than the standard A40. But it was roughly the same price as an MG TD Midget, and in the all-important US market it was priced at $2200, which just so happened to be the average price for new car on the American market in 1950.

Unfortunately, like the A90 Atlantic, the Austin A40 Sports did not tempt Americans. Only 643 of the 4011 examples made were sent Stateside. The issues were obvious; it was expensive and, despite its name and looks, was not sporty. With a top speed of just under 80mph and a 0-60mph time of over 23 seconds the A40 Sports was really little more than a glamorous, nicely-trimmed drop-top version of the standard A40.

A compact, economical, easy-to-maintain and solidly-built four-seater tourer with 1.2-litre engine, a cruising speed of 50mph and a big boot made a certain amount of sense in Britain, but the Americans were not willing to put up with such modest performance and dainty size in something that purported to be a ‘proper car’. They still favoured the MG T-type, of which nearly 10,000 per year were shipped to America while the A40 Sports mustered under half those sales in total during the three years it was available.

Austin did mount some publicity stunts with the Sports, including driving one around the coastline of Britain (as closely as possible) and then driving one 30,000 miles around the world, which proved its reliability and its credentials as a tourer rather than a sports car.

The A40 Sports was yet another disappointment for Austin’s American ambitions, although there can never have been much hope of selling the car in large quantities. The production process limited capacity to little beyond what was achieved – three rolling chassis were driven from Longbridge to Jensen’s West Bromwich works each weekday morning, the bodies were mounted and the cars driven back to the Austin works for completion and despatch. Even at this steady rate the A40 Sports work was by far the biggest order, in terms of pace and volume, that Jensen had ever had. If the project was something of a dud for Austin, it was a major boon for Jensen.

Leonard Lord did finally get his sought-for American success story. In a similar way to how the A40 Sports came into being, Lord noticed that racing driver-turned-constructor Donald Healey was buying A90 drivetrains and running gear. Investigations showed that Healey was working on a modern high-performance sports car and when the resulting Healey Hundred was shown at the London Motor Show in October 1952, Lord was so impressed that he entered into a supply and production deal with Healey, leading to the creation of the Austin-Healey marque.

A40 Sports production ended in April 1953 and Jensen was gratified to take on the production of Austin-Healey 100 bodies. Sales of the sports car began the following month and the car’s success across the Atlantic was swift. October of 1953 would also see the beginning of Austin’s tie-up with Nash to build the American-designed Metropolitan compact car. Both of these projects, and the switch to more domestic matters as the British economy recovered with products such as the little A30 and the new A40/A50 Cambridge would see the A40 Sports largely forgotten.

But that was an awfully long time ago. What is it like to own and drive one of the 20-or-so surviving A40 Sports in the UK? Many cars make somewhat more sense as classics than they did when new, and a small, stylish, coachbuilt car with a rot-proof body and common mechanical underpinnings seems to have a lot to recommend it.

Dave Fry’s 1952 A40 Sports has been in his family for 29 years and in his care for 16 of those years. Before it came into the family the previous owner had carried out a fairly extensive restoration but Dave has also done a lot of work himself to finish off what was started and keep on top of the various things that are part and parcel of owning a near-70-year old car.

Most significantly, the A40 was subject to a light rear-end shunt which stove in most of the rear body panels. “The parts coverage for mechanical spares for these is 100 per cent,” Dave told me. “A lot of the components are standard off-the-shelf BMC parts but the body is bespoke and largely hand-built. Fortunately I was able to find new rear panels from a donor car which was being broken up.”

The opportunity was taken to change the A40’s colour from the original light green, the current colour a shade used on the 1980s Citroën 2CV Dolly special edition.

Dave has fitted a new cylinder head to the otherwise standard 1200cc engine so the A40 now runs on unleaded petrol and carried out quite a lot of electric work to put right the problems of an aged wiring loom. “While the body is aluminium alloy and so it doesn’t corrode,” Dave said, “you have to watch for electrolysis around the mounting points and of course the chassis is still steel and does rust.” Dave has done quite a lot of metalwork on his A40’s frame, with repairs to the chassis legs, replacement outriggers and newly-fabricated sections on those all-important boxed-in sills which give the drop-top A40 its strength.

Dave’s A40 Sports gets regular use travelling to shows and general rural pottering around Cornwall and Devon. “I’d say I’ve covered 20,000 miles or so in the time I’ve owned it,” he estimates. “It has a towbar and if we’re going away for a weekend we’ll take a trailer of camping gear. Of course it’s not fast with the a trailer on the back but it’s not like you’re ever in a hurry when you drive an A40 Sports.”

That said, Dave has a lead on the engine from a Riley One-Point-Five (a later 1489cc B-Series version of the A40’s 1200cc unit) which will drop straight into the A40’s engine mounts and mate to the transmission without any modifications. “The Riley engine would have nearly 70 horsepower against the 46 it’s got at the moment, so it wouldn’t be working as hard on the local hills. While I’m not really fussed about going any faster it would be nice to maintain a bit of speed sometimes!” Of course, such a conversion would be entirely reversible and Dave would keep the original engine if he did the upgrade.

But for now the A40 retains its original 1.2-litre engine. How is it to drive? “Every inch a sports car, every mile a pleasure… the A40 Sports has a sparkle in its performance” is how the brochure described the car back in 1952

It doesn’t take long seated in the A40’s elegant interior, behind the grey-marbled steering wheel rim and the red leather-coasted dashboard, to realise that Austin’s copywriters were over-egging things. There are plenty of long, gruelling inclines in Cornwall and I wouldn’t say the A40 Sports surged up any of them, or that its performance ever sparkled. I don’t think it ever did, even in a world of sidevalve Fords and petrol rationing. But there is definite truth in the ‘every mile a pleasure’ bit, for the A40 Sports is, in a straightforward sort of way, a nice car to drive.

The mushroom-like clutch and brake pedals, and the tablespoon-like accelerator, are familiar to anyone who’s driven one of the Sport’s less glamorous siblings. So is the wand-like column-mounted gearlever, with lots of vertical travel and a light, rather vague action that needs a careful hand to get the right gear and a considerate treatment on the down-changes to give the synchromesh time to do its job. There’s a steady rhythm to get into as the 1200cc engine churns away with its reassuring all-iron rasp and with its small capacity it doesn’t give a lot of ‘shove’ but it has a nicely exploitable flat torque curve, and pulls well in its mid-range. It doesn’t seem to mind being worked so long as you don’t ask it to carry a lot of revs.

The open-top experience is really the only objective thing the Sports offers over the standard A40 but that’s no bad thing. It is otherwise an unprepossessing but equally undemanding car to drive. The steering has a certain amount of play in it (even allowing for the slop inevitable in any system of this type, Dave does say that a new set of steering joints are on the to-do list!) and there is therefore a constant need to wiggle the wheel back and forth to hold course, but the A40 doesn’t wander or shudder around the road, thanks to its nicely-judged independent front suspension and there isn’t much effort needed to guide the Sports along.

The ride is a mixed bag, with a noticeable amount of under-damped bounce in the front and a typical leaf-sprung thump/bump at the back. But the imperfections of Cornish backroads are soaked up in a decent way, even if there is the typical body-on-frame shudder over the larger potholes. What is a pleasant surprise is that there doesn’t seem to be any more scuttle shake than in an A40 saloon. The fact that most of the car’s strength is in the chassis, and the additional box sections put under the floor are almost certainly the things to credit here.

Briefly running on a downhill section of dual carriageway showed that the Sport can manage a comfortable, and breezy, cruise at 60mph which is enough to make good progress without making the mechanical parts or the roadholding feel strained. On the other side of the valley the A40 put up a gallant fight to maintain its momentum but before long we were back to a full-throttle climb at about 45mph.

It’s those sorts of speed that the A40 Sports is best suited to, proving again that it is badly named. Which does it a disservice, because as a classic car for touring or pottering about it makes a very good case for itself. Austin was certainly onto something with the idea of dressing humdrum underpinnings in a glamorous body and a nice interior. Nearly seven decades after its launch the A40 Sports still turns heads as well as bringing pleasure, if not thrills, to those lucky enough to own one.