Andrew Everett ponders the vanishing BMC 1100…

Attend any classic car show and you’re guaranteed to find half a dozen Morris Minors. You’ll often see one on the road at least once a week. A huge spares back up is there for remanufactured parts, and as far back as 1980 the late Charlie Ware was promoting the Minor (quite rightfully) as the classic car you can use everyday: cheap to buy, decent to drive, loads of spares and generally pretty easy to work on.

But BMC made an altogether better car with better handling, better ride, discs up front, independent suspension all round, front wheel drive and with astonishing interior room. From the same hand as the Minor came the BMC 1100, Britain’s best selling car and one that ought to have replaced the Minor in 1962 yet due to caution from the manufacturer, didn’t. The last Minor was built in 1971 and the last of the regular 1100/1300 cars followed just two years later.

The ADO16 was the car that had it all. Styled by Pinin Farina with more than a hint of the 101/750 Alfa Giulietta Coupe from behind, the 1100 captured the imagination from the word o. Whilst there was still some reticence due to the lingering reliability issues of the Mini, the 1100 was a far more sophisticated product and like the Mini was sold far too cheaply – the more expensive badge engineered versions put that to rights to some extent but the 1100 was never a car that generated big profits for BMC – just as well they sold 2.2 million of them then.

With two giant car factories pumping out 1100s and still not meeting demand, BMC ought to have discontinued the likes of the Austin A40 Farina and A35 van by 1964 when it was clear what a winner this was. The Minor could have followed shortly after, freeing up two production lines. That 2.2 million could easily have become three million and with some clever cost cutting (did the 1100 and Mini really need different gearbox and remote gearchange housings?) as well as cutting the model range from six to three or four. Did they really need a Riley Kestrel?

But that was BMC’s madness and the reason it was pretty much bankrupt by 1967. The 1100 was joined by the much better 1300 in late ’67 with more power and torque, a synchronised first gear, better brakes and seats. It sold strongly to the very end because although by 1970 folk knew that they could rust a bit, they were only keeping it for three years and it would last that long. It wasn’t like today where we expect a five to ten-year old car to be rust-free and mechanically good. Back then a five-year old car was halfway through its life and everyone knew it.

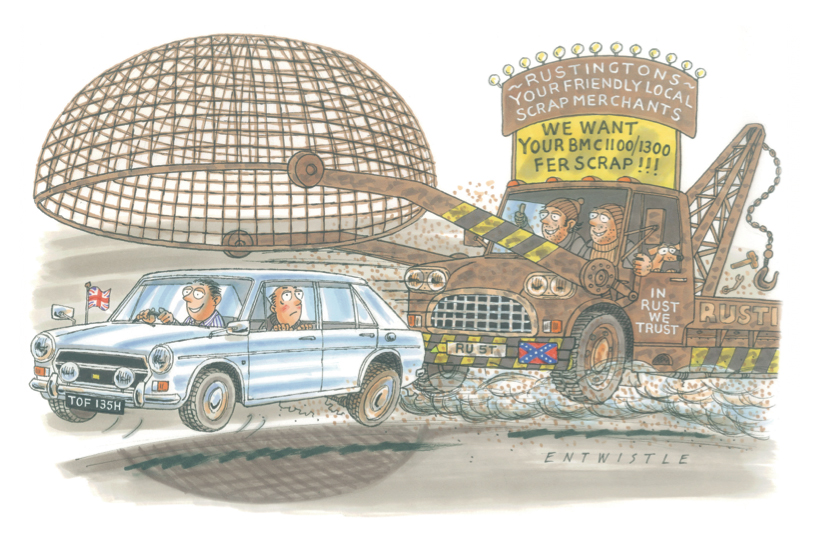

But the 1100 rusted more than anything else. Anglias and Vauxhalls showed severe rust in the wings, arches and the obvious bits, but 1100s rusted underneath. Where an Anglia chassis leg or spring hanger was an easy fix, 1100s were an absolute nightmare to weld up. If the rear subframe’s forward mounting points (under the rear seat) needed welding, you had to depressurise the Hydrolastic, undo the pipe unions (not that bad really), drop the rear subframe and spend hours rebuilding the box sections whereupon you’d find the rear of the sills were toast as well. Many 1100s were hoisted onto the back of a scrap truck without the rear subframe after the owner received a call from the welder. “It’s a bit worse than we thought…” By the time the last cars were being built in 1973 and 1974, scrap 1100s were absolutely everywhere. Early ones were being welded up for the MOT by the late Sixties and such was the poor reputation that many welders just didn’t want to know.

All was not lost though because the 1100/1300 was a superb engine donor for a Mini. My own mother’s 1962 Cooper 997 received an engine from an MOT-failed 1966 MG1100 in 1973 courtesy of a guy called Bill Mather, an American who lived in Somerton and was a mechanic for Vincents of Yeovil, the local BL dealer. A day of swearing, a swap of final drives and the job was done with a healthy 55 bhp and loads of torque – they did go well. Scenario two was from 1974 when a family friend drove their 1968 Morris 1100 for too long with a noisy idler gear, destroying the whole power unit.

No problem though as Cross Keys Motor Salvage in Lydford had plenty. “That beige Austin has just come in. It runs lovely. 15 quid and we’ll take it out now.” Armed with a borrowed Escort 7CWT van, the low-mileage 1965 engine was on its way home, chopped out in half an hour, oxy-acetylene torch through the exhaust and driveshafts and fitted that afternoon where it would end its days in the Morris in 1980.

Lastly was TOF135H, a glacier white 1300GT bought in 1984 for £60. The engine was due to be fitted to a go-faster Metro we were building from a bare shell and this GT was absolutely mint. Every panel was spotless, the interior like new and it went like a rocket. “This is just too good,” said Everett Snr, but when the rear subframe fell out as the car was jacked up, we knew it was party over.

Today of course, all three cars would have been saved. All three looked smart but hid a terrible secret of rust that was just too much of a nuisance to repair – and that was over 40 years ago.

I like 1100s a lot. Mini and Minor apart, they were about the first British cars to show British buyers how good a small inexpensive car could be and I always wondered who would have driven one and thought “no, I really want drum brakes, cart springs and ball and pray steering.” The answer was that BMC couldn’t satisfy demand – a position it was never to be in again until the first Metro.